Paul Yates discusses how to solve them and their applications

A linear equation with a single unknown is relatively straightforward to solve. For example

x + 7 = 11

We can subtract 7 from both sides to give the answer x = 4.

However, if there are two unknowns, such as

x + y = 4

there are various of values of x and y that will satisfy the equation. In this case we could have x = 0 and y = 4; x = 1 and y = 3; x = y = 2; x = 3 and y = 1; or x = 4 and y = 0. There are also an infinite number of non-integer answers. To find the values of x and y we need more information.

Let’s suppose we are also told that

x – y = 2

These two equations are known as simultaneous equations because they are true simultaneously. In general, we need as many equations as we have variables to be able to determine their values.

There are various ways of solving simultaneous equations. Laura Woollard has discussed three methods: elimination, substitution and graphical analysis.1 She concludes that the elimination method is the most appropriate for year 10 students, particularly those who are less able. Janet Jagger, however, argues substitution is a more versatile method for solving them and therefore advocates this approach.2 Doug French argues both approaches are important.3 More intuitive methods based on inspection have been discussed by Paul Chambers.4

I will give some examples, both generic and chemical, that illustrate the techniques used in solving simultaneous equations without getting too concerned about labelling the methods.

In the example above, it should be evident that if we add the equations together, the terms in y will cancel out:

(x + x) + (y − y) = 4 + 2

which becomes

2x = 6

and dividing both sides by 2 gives x = 3. We can substitute this value into the initial equation, giving

3 + y = 4

Subtracting 3 from both sides gives y = 1.

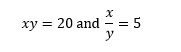

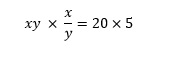

As another example consider the pair of equations

This time we need to recognise that multiplying the equations together will eliminate y, so that

which simplifies to

x2 = 100

Taking the square root of each side gives the solution x = 10. Substituting into the first equation then gives

10y = 20

and dividing both sides by 10 gives y = 2. There is also a solution with the corresponding negative values since −10 is also a square root of 100.

There are relatively few places in chemistry where we need to solve simultaneous equations, but three examples are given below.

Vapour pressure

The vapour pressure p above a mixture of two liquids is given by the equation

p = x1 p1* + x2 p2*

where x1 and x2 are the mole fractions of components 1 and 2 of the mixture, and p1* and p2* are the corresponding vapour pressures of the pure solvents.

The vapour pressure above a mixture containing 0.6 mole fraction of toluene in benzene is 6.006 kPa and falls to 5.398 kPa when the mole fraction is increased to 0.7. With this information we can set up the equations

6.006 = 0.6 p1* + 0.4 p2*

and

5.398 = 0.7 p1* + 0.3 p2*

If we multiply the first equation by 0.7 and the second by 0.6, we obtain a pair of equations in which the coefficients of p1* are equal (similar to how one might use the lowest common denominator method to add and subtract fractions).

4.204 = 0.42 p1* + 0.28 p2*

3.239 = 0.42 p1* + 0.18 p2*

If we now subtract the second modified equation from the first we have

(4.204 − 3.239) = (0.42 − 0.42) p1* + (0.28 − 0.18) p2*

which simplifies to

0.965 = 0.1 p2*

Dividing both sides by 0.1 gives the vapour pressure of pure benzene, p2* = 9.65 kPa.

Substituting this value into the initial equation gives

6.006 = 0.6 p1* + (0.4 x 9.65)

∴ 6.006 = 0.6 p1* + 3.86

Subtracting 3.86 from both sides gives

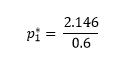

2.146 = 0.6 p1*

and dividing both sides by 0.6 gives

So the vapour pressure of pure toluene, p1*, is 3.58 kPa.

The Arrhenius equation

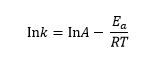

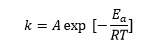

This tells us that the rate constant, k, for a reaction is related to the absolute temperature, T, by the equation

or

where Ea is the activation energy for the reaction, R is the gas constant and A is a constant called the pre-exponential factor.

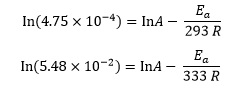

For the decomposition of 3-oxopentanedioic acid,5 the rate constant is 4.75 × 10−4 s−1 at 20°C and 5.48 × 10−2 s−1 at 60°C. We can convert these temperatures to 293 K and 333 K respectively (by adding 273) and set up the Arrhenius equation for each set of data to give equations in A and Ea

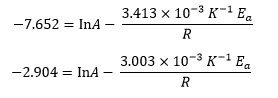

We can evaluate the natural logarithms and reciprocals to give

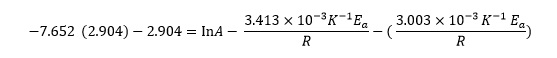

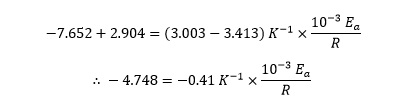

The simplest way to eliminate one of the variables is to subtract one equation from the other, so the ln A terms cancel. We then have

which simplifies to

Multiplying both sides of this equation by –R then gives

4.748 R = 0.41 K−1 × 10−3 Ea

and dividing both sides by 0.41 × 10−3 K−1 gives

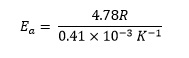

Finally, substituting the value of the gas constant R gives

or 96.3 kJ mol−1, since the initial data is given to three significant figures.

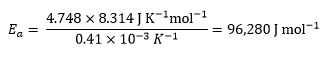

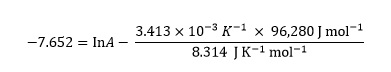

Substituting into either of the original equations allows them to be solved for A

Combining the numerical terms on the right gives

−7.652 = lnA − 39.524

Adding 39.524 to both sides gives

lnA = 31.872

Finally, taking the exponential delivers a value for A

A = e31.872 = 6.95 × 1013

Steady state approximation

Finally, simultaneous equations arise when we analyse the mechanisms of multistep reactions by studying their kinetics. For example, N2O5 decomposes spontaneously according to the following stoichiometric equation

2N2O5 ⇌ 4NO2 + O2

which can be broken down into a set of elementary steps, each with its own simple rate law:

N2O5 + M ⇌ NO2 + NO3 + M

(Rate constants k1 and k2 for forward and reverse reactions respectively)

NO2 + NO3 → NO + O2 + NO2 (Rate constant k3)

NO + NO3 → 2NO2 (Rate constant k4)

In these reactions, M is a chemically inert gas.

It is useful in the kinetic analysis to be able to express the concentration terms of the reactive intermediates NO and NO3 in terms of the species that appear in the final stoichiometric reaction equation (ie N2O5 and NO2). This can be done by assuming they are in the ‘steady state’, such that their concentrations are constant, and therefore the rates of change of those concentrations are set to zero. This kinetic analysis gives a pair of simultaneous equations in the two variables [NO] and [NO3]

k1[N2O5][M] − k2[M][NO2][NO3] − k3[NO2][NO3] − k4[NO][NO3] = 0

k3[NO2][NO3] − k4[NO][NO3] = 0

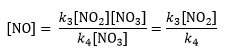

Dividing both sides of the second equation by k4[NO3] gives an expression for [NO] that is independent of [NO3]

From the second original equation, we can see that k3[NO2][NO3] = k4[NO][NO3]. Substituting this into the first equation eliminates the [NO] term

k1[N2O5][M] − k2[M][NO2][NO3] − 2k3[NO2][NO3] = 0

Collecting the terms in [NO3] gives

k1[N2O5][M] – [NO3]{k2[M][NO2] + 2k3[NO2]} = 0

which rearranges to

[NO3]{k2[M][NO2] + 2k3[NO2]} = k1[N2O5][M]

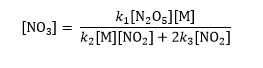

Finally dividing both sides by {k2[M][NO2] + 2k3[NO2]} gives a solution for [NO3]

Paul Yates is acting director of learning and teaching at the Learning and Teaching Institute, University of Chester, UK

References

- L Woollard, The STeP Journal, 2015, 2, 88

- J M Jagger, Mathematics in School, 2005, 34, 32

- D French, Mathematics in School, 2005, 34, 30

- P Chambers, Mathematics in School, 2007, 36, 30

- R J Silbey and R A Alberty, Physical Chemistry (3rd ed). John Wiley, 2001

No comments yet