Despite being one of the rarest elements on Earth, selenium is an essential nutrient. But our diets contain less selenium now than ever before. Does this put our health at risk?

The Department of Health's recommended daily selenium intake is 75 μg (micrograms) for men and 60 g for women. That's about the amount contained in a small can (20-25 g) of tuna. Other selenium-rich foods include Brazil nuts and kidney while beef, shellfish and chicken also contain relatively large amounts of the element. In general, however, selenium intake in Europe has fallen dramatically in the past 30 years. The average person in the UK now gets about half of the recommended amount in their diet.

Scientists believe the problems began when the UK stopped importing Canadian wheat and switched to home-grown varieties. Canadian bread-making wheat can contain up to 50 times more selenium than the UK equivalent because it is grown in soil that is naturally selenium-rich. In contrast UK soil contains very little selenium. What, then, is the role of selenium in the body, and are such deficiencies a cause for concern?

The selenoproteins

Selenium is found in the body in 'selenoproteins' (refer to Box). There are 25 human selenoproteins. One of the most important is the enzyme glutathione peroxidase (GPx). GPx is an antioxidant which protects cells from damage by molecules such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and lipid hydroperoxides. These highly reactive molecules are formed naturally in the body and are essential to health. They form reactive oxygen species (often radicals where the oxygen has an unpaired electron) which kill cells by reacting with the cell walls.

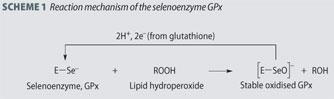

Luckily for our cells, when GPx encounters lipid hydroperoxides it reduces them to harmless alcohols, or in the case of hydrogen peroxide, water. The Se atom in GPx attacks the peroxides and is converted to a stable, oxidised product. Enzymes are biological catalysts, so they must return to their original state after performing a reaction. Another molecule, glutathione, replaces the two electrons lost by selenium in the reaction, so GPx is then ready to do it again (Scheme 1).

Dr Margaret Rayman of the University of Surrey, Guildford, UK studies the effect of selenium on human health. She explained to InfoChem that if we eat less than the recommended amount of selenium we won't get the maximum protection that GPx can offer. And severe selenium deficiency can cause other problems.

Health issues

The best-known example of disease related to selenium deficiency occurred in rural China. A heart-related illness, which first appeared in the 1930s, claimed thousands of lives at its peak in the 1960s and 1970s. The condition became known as Keshan disease, after the district where the first cases were noted. When Chinese scientists investigated the disease in the 1960s they found that it occurred in a belt crossing the country. By analysing soil and crops from this area, along with hair samples from local residents, they found lower selenium levels than in the rest of the country.

As part of a clinical trial the scientists gave people living in the affected area selenium supplements in the form of Na2SeO3 over a 10-year period. The results of this trial indicated that the supplements reduced the incidence of the disease.

Since then researchers have been investigating the link between selenium in the diet and various illnesses, including cancer. The Nutritional Prevention of Cancer (NPC) Trial, conducted in the US in the 1980s and 1990s is the largest study in this field to date. In the 10-year trial, 1312 volunteers, who had previously had skin cancer, were given either 200 μg of selenium (as selenium-enriched yeast tablets), or a placebo pill containing no selenium. At the end of the trial the patients in the selenium group had 37 per cent fewer cancers than the people who had taken no selenium and 50 per cent fewer of the selenium group had died. There were 46 per cent fewer lung cancer cases, 58 per cent fewer bowel cancers, and 63 per cent fewer cases of prostate cancer in the people who had taken selenium than in the placebo group. The scientists concluded that selenium is a key anti-cancer nutrient.

The scientists reasoned that antioxidant selenoenzymes such as GPx would mop up reactive oxygen species that can cause cancer when they react with DNA. But Rayman points out that the NPC trial used doses of selenium that were higher than is required for GPx alone, which suggests that selenium has other cancer-fighting actions.

Basically, selenoenzymes are not the whole story. Rayman explained that when we eat foods that are rich in selenium compounds, they are converted into a number of small organic molecules (metabolites) which are either incorporated into proteins or pass out of our body again. Some of these metabolites are thought to combat cancer, especially methyl selenol (CH3SeH). These compounds are thought to disrupt the pathways of chemical signals that tell healthy cells to become cancerous tumours. Methyl selenol can also prevent tumours from developing new blood vessels, so the cancer grows more slowly.

Too much of a good thing?

As well as encouraging us to eat more selenium-rich foods, scientists are currently working on ways to boost our selenium levels which are also important to our immune response. In 1984, the Government of Finland passed a law to make farmers add selenium to the soil in fertilisers. This has successfully increased Finnish people's average selenium intake up to the recommended level. At the Institute of Food Research in Norwich, UK nutritionists are researching the effects of dietary supplements and selenium-enriched onions on selenium levels in the body.

Finally, a word of caution: selenium can be toxic at high levels. The World Health Organisation recommends no more than 450 μg per day. Symptoms of selenium toxicity include hair and nail loss, nausea and even death. So be careful when you reach for the Brazil nuts this Christmas.

Selenoproteins - the facts

Most selenium in the body is found in proteins. Proteins are formed when different amino acids are joined together end-to-end in a long, folded chain. Enzymes are proteins that act as biological catalysts.

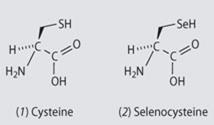

Selenoproteins are proteins which incorporate the amino acid selenocysteine. Selenocysteine is similar to the more common amino acid cysteine but with a selenium atom instead of sulfur.

Selenocysteine's selenium atom is more acidic than cysteine's sulfur. In the body cysteine is protonated but selenocysteine contains the Se- anion. This negative charge makes selenocysteine much more reactive than cysteine and dominates the function of selenoproteins.

Selenium can donate and accept electrons, which makes 'selenoenzymes' versatile catalysts.

No comments yet