A look at recent chemical science research, contributed by the chemistry world team

A nanoscale antenna that can collect light and convert it into a current shows promise for energy harvesting applications, say its US developers. These nanoantennas could be combined with conventional solar cells to increase the portion of visible light that they can turn into electricity.

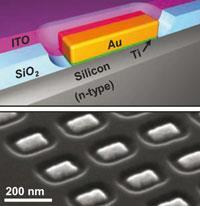

Just as a car antenna can pick up radio waves, an optical nanoantenna can receive light waves. Naomi Halas and colleagues at Rice University in Houston have taken the concept of the optical nanoantenna one stage further to make a photosensor. They combined nanoantennas that detect light, with a photodiode that converts light energy into an electrical current.

The team grew arrays of gold nanoantennas, between 110 nm and 158 nm in length, directly onto a silicon semiconductor surface and exposed the device to infrared radiation. Halas explains that the length of the nanoantennas is very important as the wavelength of light detected - in this case infrared - corresponds to the length of the nanoantenna used.

She explains that the absorbed infrared radiation is turned into 'hot' electrons - highly energetic electrons - which can jump the barrier between the gold and the silicon to produce a current. Halas believes the device has a 'unique capability for light harvesting that could significantly advance devices such as solar cells'.

Martin Cryan, an expert in nanophotonics at the University of Bristol, UK, believes this is an exciting new direction for optical antennas. 'This work includes the photon to electron conversion function, which is important for both energy and information processing and could lead to many new technological developments in both these areas,' he says.

David Andrews, an expert on energy harvesting materials from the University of East Anglia, also in the UK, speculates that Halas's design could lead to the development of relatively cheap detectors operating in the near infrared region, 1250-1650 nm. But at this stage he is concerned about the efficiency of the device, which is about 1 per cent. 'The target efficiency will be too small for realistic energy harvesting purposes; the real applications are likely to lie in the realm of photosensing and imaging,' he says.

Halas concedes that more work is necessary to improve the efficiency of the device. 'There are numerous ways we can improve the current efficiencies by refining the device design and exploiting the same physical principle,' she says. 'Our device is a marriage of nanoscale optics with electronics, and we anticipate that it will stimulate further advances in the convergence of these fields,' she adds.

References

- Halas et al, Science, 2011, 332, 702 (DOI: 10.1126/science.1203056)

No comments yet