Obesity is fast becoming endemic in the developed nations, do anti-obesity drugs have a part to play in its control?

By 2050 scientists predict that a third of all men and half of the women in the UK will be ‘obese.’ Equally alarmingly, by this date, 25 per cent of under 20s and 50 per cent of all 6–10-year olds in the UK are expected to fall into this rotund state. Similar data are found in the rest of Europe, and in the US the problem is worse.

… by 2050… 50% of all 6–10-year olds in the UK will be obese

How do we classify obesity?

People with a BMI (body mass index) of 30–40 are classified as obese. The BMI is calculated from the following equation:

BMI = weight in kg / (height in m)2

A BMI between 25–30 is deemed ‘overweight’ and over 40 is ‘morbidly obese’.

Unfortunately being obese comes with serious health risks. Obese people are much more likely to develop type 2 diabetes compared with people who are not. Type 2 diabetes is associated with a loss of response of the liver, muscles and fat tissue to insulin. This hormone (a chemical messenger molecule) controls the production and use of the body’s energy source (glucose). Insulin resistance can lead to high levels of glucose in the blood which is toxic and can lead to damaged organs. Coronary heart disease, stroke, osteoarthritis and cancers of the colon, prostate and breast are also more common among obese people than the general population.

Unfortunately the ‘leaner diet, more exercise’ approach has a poor record when it comes to treating obesity. And when all else fails many morbidly obese people turn to surgery which, though effective, comes with its own risk. Over the past 30 years, however, there has been a growing interest in the development of drug therapy to treat obesity. Many pharmaceutical companies are investing millions in what might become tomorrow’s blockbuster drug.

Early anti-obesity drugs

The idea of an anti-obesity drug is not new. People have been using herbal remedies for aeons to control their weight with debatable success. Extracts from the Hoodia cactus found in the Kalahari desert, for example, were apparently used by tribes to suppress their appetite as they went in search of food. Over the past couple of centuries, however, several synthetic drugs to control appetite have come and gone because their side effects outweighed the benefits.

In the late 1890s chemists used a thyroid hormone, extracted from thyroid glands, to treat obesity. This natural product led to weight loss by increasing the body’s metabolic rate, and thus energy expenditure. However, the hormone also caused heart problems, excessive protein and water loss as well as fat loss, and so was abandoned. Ideally an anti-obesity drug should target fat only.

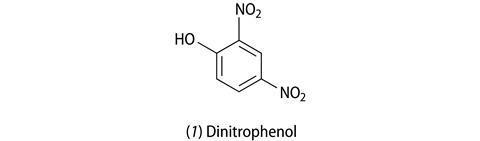

In 1933 2,4-dinitrophenol (1, DNP) was the active ingredient in diet pills. DNP had been used extensively in the manufacture of explosives during World War I, and was linked to the weight loss of women who worked in munitions factories and had to handle this chemical. As a fat fighter, DNP works by uncoupling a specific metabolic reaction (oxidative phosphrylation), which has the effect that fuels (sugars and fats) are burnt without the production of ATP (adenosine triphosphate) – the molecule that supplies energy for cellular processes. Some of the wasted energy ends up as heat, which sometimes led to fatal fevers and so DNP diet pills were withdrawn from the market.

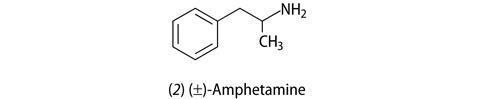

By the late 1930s scientists had stumbled on the fact that amphetamine use led to weight loss. Amphetamine (1-phenyl-2-aminopropane, 2) was being used to treat depression and anxiety as well being abused as a ‘recreation’ drug for its performance-enhancing effect. The stimulant effect is caused by the release of the chemical messenger molecules noradrenaline and dopamine from brain cells (neurons). As a side effect patients and addicts lost weight probably because of their increased energy expenditure as they became more active, or hyperactive. However, side effects – raised blood pressure, agitation, irritability, nervousness – again stopped its use as an anti-obesity drug.

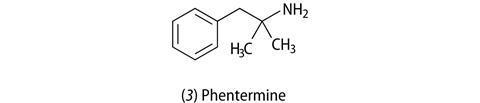

Other anti-obesity drugs that were related to amphetamine, in terms of their structure and their mode of action in the body, followed. Phentermine (3), which had less severe side effects to amphetamine and was not addictive, is still prescribed today in the US for short-term use (up to three months). Others had limited success.

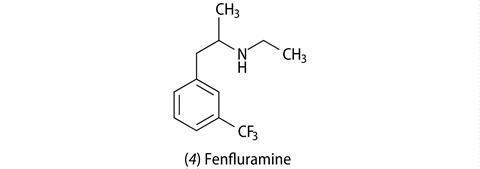

In 1973 fenfluramine (4), as the racemic mixture (containing both chiral isomers), came on the market. Although similar to amphetamine-like drugs structurally, fenfluramine stimulates the release of a different chemical messenger molecule – serotonin – and inhibits its re-uptake by neurons, which has an appetite-suppressing effect. The drug was used for 24 years in Europe for treating obesity, and eventually the more active d-isomer was licensed in the US. However, the Americans discovered that d-fenfluramine caused heart-valve defects and irregular heart beats, and the drug was withdrawn worldwide.

Today’s offerings

Today there are just two prescription drugs available for treating obesity, though many others are in clinical trials, some of which have sought to improve on older remedies others take a completely new line of approach.

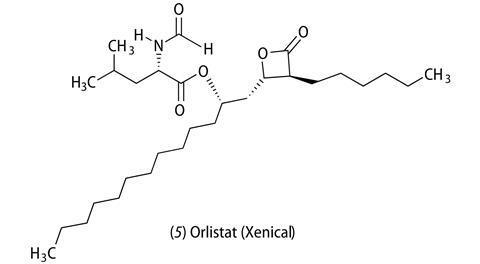

Orlistat (5) which was developed by Swiss chemists came on the market in 1987 as Xenical. The drug works by inhibiting the digestion of fats and carbohydrates in the intestine. Specifically, it inhibits the enzyme pancreatic lipase, which breaks down triglycerides into monoglycerides and free fatty acids, which can then be absorbed into the gut. Orlistat has recently been approved for use in the US and in Europe as an OTC (‘over-the-counter’ medication) at half the strength of Xenical, and this is being marketed as alli.

The big advantage of orlistat is that it is safe, the only side effects being some discomfort in the stomach and faecal incontinence. (The latter has the added advantage that it encourages patients to eat less fat.) There was initial concern that patients on orlistat may become deficient in fat-soluble vitamins, but this is unlikely because most people have too much fat in their diet anyway.

Orlistat gives an average weight loss of 2.8–2.9 kg (ca half a stone), which plateaus after about six months. It doesn’t amount to much cosmetically but the regulators are more interested in its potential medical benefits – even small weight loss is significant in terms of reducing blood pressure, the risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

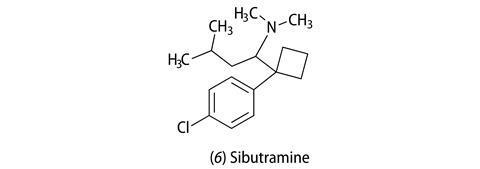

The other drug currently available on prescription is sibutramine (6) (Reductil). This tertiary amine was originally investigated as an antidepressant, but failed in clinical trials and again by chance the researchers noticed that it caused weight loss in users. As an anti-obesity agent it works like many antidepressants – it inhibits the re-uptake of noradrenaline and serotonin into neurons after they have been released in the brain. It is mainly viewed as an appetite suppressant but some scientists hypothesise that it also increases energy expenditure. However, among its side effects are raised heart beat and blood pressure, which for the obese person, who probably already has high blood pressure, is not ideal. In clinical trials the drug, taken for 12 months gave 4.2–4.4 kg weight loss, plateauing at around six months. So, potentially, the weight loss could compensate for the tendency of the drug to raise blood pressure. The drug is only licensed for use, like orlistat, for up to 12 months.

A steroid-based compound (P57) has recently been isolated from the Hoodia cactus and is under investigation as a potential anti-obesity drug, but hasn’t yet received approval in terms of its safety and efficacy.

Drug companies are now taking a more rational approach to the design of anti-obesity drugs. The discovery in 1994 of the hormone, leptin, that regulates hunger in the brain by controlling the release and uptake of small peptides is leading to new targets for such drugs, some of which are in clinical trials.

With or without the drugs, healthy eating and regular exercise are still the recommended first line of attack to reducing weight.

Acknowledgement: this article is based on an interview with Jon Arch, professor of metabolic research at Buckingham University.

This article was originally published in The Mole

No comments yet