It is structural tricks, not pigments that give blue fruits their attractive hue

-

Download this

Use this story and the accompanying summary slide for a real-world context when studying nanoparticles with your 14–16 learners.

Download the story as MS Word or PDF and the summary slide as MS PowerPoint or PDF.

Despite their name and appearance, blueberries do not contain any blue pigments. New research attributes their blue hue to interactions between light and the nanostructures found in their waxy coating. Researchers suggest that further investigation of this wax in the laboratory may help inspire sustainable, coloured biomaterials that can self-assemble and self-heal.

Several blue fruits, including blueberries, damsons and sloes, feature a waxy epicuticular coating that protects them from predators and pathogens. While these fruits are rich in dark red anthocyanin pigments, the coating makes them appear blue. Vertebrates can see blue light well and such fruits are attractive to them, but blue-reflective pigments are rare in living things. Nature more commonly uses structural colouration — the use of microscopic structures on surfaces that change how light is reflected. This trickery is seen in bluebells and some butterfly wings and bird feathers.

A clever trick of light

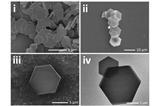

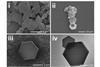

Researchers from Germany, Finland and the UK teamed up to sample a variety of blue fruits with waxy coatings. Analysing the coatings with scanning electron microscopy revealed randomly arranged, non-spherical nanostructures that interact with light, scattering it to create their blue hues. Across a range of fruits, the researchers found four wax crystal shapes: ring, rod, slab and tube. Despite differences in the morphologies of the wax nanostructures, they all produced very similar optical spectra and look alike to humans.

The scientists then probed the coatings further. First, they washed the wax off the berries of the Oregon grape plant. Next, they recrystallised it onto card. Although the fruit wax appeared transparent when in solution, and white as a solute, when it was spread onto card, it self-assembled into a nanostructure with the same deep blue colour as the natural berry.

The researchers believe fruit wax could inspire the design of novel non-toxic, self-assembled colourants and coatings. Due to the wax’s ability to self-assemble, these biomaterials could also be self-healing, meaning they could repair themselves if scratched or torn.

This article is adapted from Ada McVean’s in Chemistry World.

Nina Notman

Reference

R Middleton et al, Sci. Adv., 2024, 10, 6 (doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adk4219)

Download this

Summary slide with questions and the article for context when teaching 14–16 classes on nanoparticles: rsc.li/3PqjBZK

Downloads

Blueberry nanostructures student sheet

Handout | PDF, Size 0.17 mbBlueberry nanostructures student sheet

Handout | Word, Size 0.74 mbBlueberry nanostructures summary slide

Presentation | PDF, Size 0.35 mbBlueberry nanostructures summary slide

Presentation | PowerPoint, Size 2.18 mb

1 Reader's comment