How chemistry keeps museum exhibits frozen in time

Gazing at old family photographs, I sometimes feel like a time-traveller behind a window looking directly into the past, to a moment frozen in time. I am always struck by the same emotions when walking through museums and galleries. Gigantic fossils of mammals and birds are placed into poses they may have once adopted when roaming the Earth.

Unlike the objects in photographs however, museum exhibits are not in fact stuck in the past. Over the years, dust and other contaminants settle on their fragile frames, while the poses they strike weaken their bones. Chemistry holds the key to preserving them.

Conservators at the Grant Museum of Zoology, University College London, UK, are undertaking a major conservation project of 39 of their rarest skeletons. Among the collection are the strange remains of an ariid catfish, the head of which resembles a crucifix, and one of the rarest skeletons in the world, the extinct quagga – a half-striped zebra. In many cases the skeletons are irreplaceable.

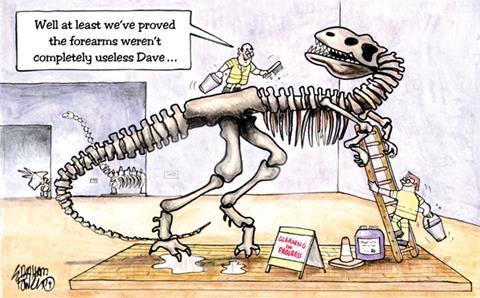

The project will involve taking the displays out of their frames and chemically cleaning them before placing the pristine skeletons back in the museum. Although the cleaning process is relatively straightforward, it will require a delicate touch.

The team at the Grant Museum first have to dry clean each of the bones with a brush, a specialised hoover, which will collect over 90% of the surface contamination, and latex sponges. Given the physical state of some of the pieces however, the conservators will also need to rely on chemical treatments to remove particles trapped in grooves and grains.

Cleaning the samples will be very similar to how laboratory equipment is cleaned, with dust being removed by applying a blend of deionised water and alcohol with cotton swabs. Simply soaking them in a water bath would lead to further damage as it would help to break down minerals within the bone.

The nature of this cleaning process means the team will be working over a long period to ensure the skeletons are in tip-top shape. To add to the project’s complexity, some of the rare specimens will have to be re-mounted in new custom-built frames.

This project, and many other conservation efforts in exhibitions around the world, illustrates the challenges museums face to keep some of the Earth’s most spectacular creatures frozen in time.

No comments yet