Helen Sharman talks science, space travel and advice for budding astronauts

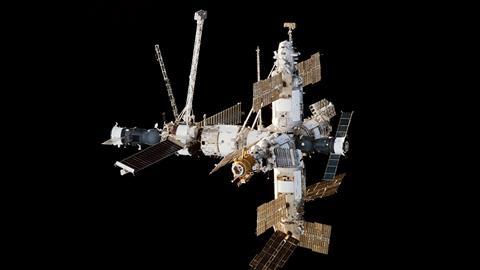

In 1989, Helen Sharman was driving home from work when she heard an advert on the radio: ‘Astronauts wanted, no experience required.’ Ahead of 13,000 other applicants, following an extensive selection process and training programme, Helen became the first Briton to travel into space. She spent eight days orbiting the Earth, visiting the MIR space station where she performed a variety of scientific experiments. Back on terra firma, Helen’s career as a chemist has taken her from Mars (the confectioner!) to the National Physical Laboratory and Imperial College London.

Education in Chemistry caught up with Helen at the RSC Secondary and Further Education Group conference in Bolton, to ask her about her earliest memories of science, her involvement in Project Juno and her advice for budding astronauts.

What is your earliest memory of science?

When I was at junior school, I remember reading about what makes things appear to be the colour that they are. And although I didn’t know anything about the specific molecules in everything I could see, I found that fascinating. And then very close to that, I read about the speed of light and I remember somebody saying, ‘What you’re seeing isn’t really what’s there now, it’s what was there a fraction of a second ago.’ That whole concept was brilliant to me, and yet it seemed so against all of our natural tendencies.

I was just always fascinated by what makes things the way they are – I didn’t know it was called ‘science’ then.

Did you have any particularly inspiring schoolteachers? What made them stand out?

I had a brilliant maths teacher. And the reason he was good was that he used to do everything from first principles. So we could understand that he wasn’t trying to fox us, he wasn’t just making up an equation that we had to learn out of thin air – he was showing how that equation had been derived and then we’d go on and use it to do other things. I loved that.

Is there anyone in your family whose example inspired you to reach for the stars, and why?

My dad was a physicist and when I was growing up he would explain stuff the way it really is, so for me science was always just useful. If I wanted to know how a vacuum cleaner works, he could tell me. If I wanted to know how to wire a plug, he could do that. It wasn’t as though it was a weird thing that could only be learned at school – he could explain these parts of life, so science was always relevant.

I also had a couple of grandparents who were, let’s say, strong of character. They had stubborn streaks. And I think they taught me about persistence – if you really want to achieve something, sometimes it is tough, but actually you’ve got to just keep on and you’ll get there in the end.

When embarking on your career as a scientist, you wouldn’t have known it would one day take you into space. How did it feel when you realised you were going to be involved in Project Juno?

Most of my training I assumed I’d be backup, until three months before the launch when I was chosen as prime and Tim Mace was then my backup. So I really never believed it would happen to me.

But when you’re sitting on the rocket on the day of the launch, that’s when you know it’s going to be you. Even if you only make it five kilometres down the road because you explode, or you’re about to explode on the launch pad, you knew you were going up somehow.

What does space travel feel like?

Feeling weightless is the most natural, relaxing thing you can possibly imagine. You forget what it feels like to sit down and feel the pressure of the seat beneath you, which we don’t think about because we get used to it. After a few weeks, astronauts’ hard skin just disappears because you’re not walking and you don’t need it. The human body is very adaptive. In fact, it’s so easy in space that’s the problem – astronauts’ bodies adapt and unless you really work hard, in terms of exercise and nutrition, then you’re not going to be strong enough to come back to Earth – going up is easy, it’s coming down that’s harder.

What has space travel done for science? For society?

We’re still doing a lot of basic blue sky research, for example using the weightless environment to grow continuous, more pure, crystals, and looking at plant growth as well. We’re starting to understand how important the environment around a plant is and why it’s harder to grow plants in space, fruit and veg particularly. It’s basic understanding in terms of the science.

Of course there’s a whole load of other things.

We’ve got the satellites that look back on Earth and all the meteorology, navigation, communications, TV, radio and all of that. We can tell if there’s deforestation or mineral mining going on in certain parts of the world, so there’s a huge amount just from the satellites.

There’s also all the spin-offs – the internet uses the timing from satellites to control all the ways that information is disseminated. There’s the miniaturisation in respirators and sensors, for example baby temperature monitors. And robotics, of course, is huge – so artificial limbs with robotic sensors. And the robotic probes that we’re sending to understand other planetary bodies, and comets, meteors as well.

Also, telescopes – that’s where chemistry also comes in useful. We’re not actually going out there, but we are looking through the telescopes and using our knowledge of chemistry and theoretical physics together to tell us about the very origins of the universe.

If you could make a scientific discovery, or claim a historical one for yourself, what would it be?

I would have loved to have found gravitational waves – LIGO did that three years ago. But what I would love to do in the future is to find, definitively, the start of life and then also to find life elsewhere.

What keeps you awake at night?

Nothing. Absolutely nothing. I sleep like a baby. But what worries me, if that’s what you really mean, is the climate – that’s the big thing.

Outside of work, how do you most like to relax?

I love walking in the mountains. It could be anywhere. The Lake District is brilliant, the Peak District is great, the Alps are amazing. Actually seeing the Himalayas from space made me realise I had to go there. And I did the following year. I did a walk around Annapurna and it’s just fabulous!

What would you like to be remembered for?

That I managed to make people consider science as part of everyday life, something that’s really important and should be used for the best purposes. We need to influence our world leaders to use science in the right way.

What life advice would you give students? Budding astronauts?

Really not letting other people dissuade you. If you really think that you want to do something, just stick out for it. You know what you want, go for it. It’s not irrevocable either – much more nowadays we can move and change, and it’s not going to be one career. It’ll be lots of jobs, it’ll be a portfolio career.

Helen Sharman was talking to Education in Chemistry’s Jamie Durrani and Julie Hyde, chair of the RSC Secondary and Further Education Group committee.

No comments yet