How can activities based around everyday objects inspire young children to study chemistry? Peter Hoare and Anne Willis explain

The Royal Society of Chemistry has a rich supply of examples of engaging outreach activities on their website that any budding science demonstrators can use. These Chemistry for our future resources are predominantly aimed at students already studying A-level chemistry to encourage them to continue further with their chemistry studies.

As experienced chemistry teachers, we could see that burgeoning chemists needed to be targeted earlier than that. We need to capture children’s imaginations at a much younger age if we are to encourage larger numbers to consider chemistry when making KS4/GCSE option choices. In September 2008, at the start of both of our one year RSC school teacher fellowships, we decided to pool our resources and focus our outreach efforts on inspiring children aged 9–14 to take an interest in chemistry.

Chemistry in your shopping basket was the result: a very portable outreach activity that only requires the venue to provide a data projector to connect to our laptop, a couple of trestle tables and a large sink to wash up between multiple presentations. Since its premiere in March 2009, Chemistry in your shopping basket has been delivered to over 17,000 students: 14,000 in schools and 3000 at science fairs.

Fit for purpose

When designing the session, we were acutely aware that for many secondary schools any activity facilitated by an external provider must have a direct link to the curriculum. We also wanted the outreach project to be set in an everyday context, to link to the audience’s existing science knowledge and experience, and to link forward to chemistry-related careers. Additionally, we wanted the activity to fit into a single timetabled lesson to minimise disruption. This led to structuring the activity into three acts:

- Act one: introduction and existing knowledge using zappers

- Act two: the items from the shopping basket and linked activities and demonstrations

- Act three: zapper questions linked to chemistry-related careers

Act one: existing knowledge

This first act uses zappers – also called PRS (personal response systems), SRS (student response systems) or clickers – to interact with the audience. Zappers are widely used at undergraduate level as a teaching and learning tool to obtain instant feedback in lectures. However, their use at school level is usually restricted to university academics using them in outreach activities. We both prefer Turning Point as our audience response system.

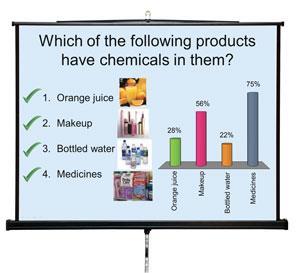

In this act, we ask a series of zapper questions covering properties, states, natural and manmade materials. These are designed to test student’s current knowledge, challenge misconceptions and introduce the idea that chemistry pervades all aspects of our lives. For example we ask the audience ‘which of these products have chemicals in them: orange juice, makeup, bottled water, medicine?’. This question is designed to challenge the often held belief that manmade products do contain chemicals (makeup and medicines) whereas natural products (orange juice and bottled water) do not. Interestingly, the results are broadly similar between KS2 and KS4, and even the KS5 results (from the 2013 A2 UCAS applicants to Newcastle chemistry degree programmes) do not show 100% for each, as we naively might hope or expect.

Act two: the shopping basket

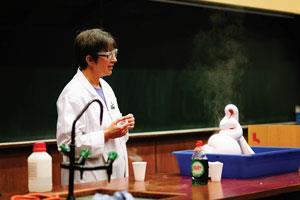

This is the main act, containing the practical demonstrations, and it is during this act that the shopping basket is used (see Shopping basket items and activities). We originally chose five themes we wanted to cover – salt, carbon dioxide, crude oil, nitrogen and UV light. These were chosen partly because we already had several classic demonstrations with the wow factor we wanted to include and partly as the chemicals they involve can easily be found in many common household items. However, the final UV theme was rapidly dropped as the activities were less engaging; this allowed us more time to develop the remaining four.

For the experiments involving salt, we need from the shopping basket: bleach, margarine, toilet rolls and soap. We first explain that salt is the raw material from which all these items are made. Next we discuss in general terms the electrolysis of brine and therefore the production of chlorine, hydrogen and sodium hydroxide. We then ask for two volunteers and tell them they are going to make ice cream using salt, this normally causes them to grimace and say ‘yuck’. Of course, the salt is actually used to make a freezing mixture with crushed ice on to which the bag containing the ice cream mixture is placed. We then discuss the use of ‘grit’ (rock salt) on roads in winter, and dispel the commonly-held myth that adding salt to ice warms it up. We also ask the audience for the melting point of ice as this later links to both the dry ice and liquid nitrogen demonstrations.

We then look at carbon dioxide, discussing its use in carbonated drinks, the thermal decomposition of baking powder during cake baking, respiration by yeast in bread production and finally as a solvent for decaffeinating coffee. Interestingly, when initially asked to identify the chemical link between these products, most audience’s first answer is ‘caffeine’ not carbon dioxide, despite having emphasised that we have shown them a jar of decaffeinated coffee. We then show them dry ice, talk about changes of state and sublimation and compare dry ice to ice. The audience now inflate balloons containing a few dry ice pellets just using the warmth from their hands. This leads to identifying the wisps of white vapour descending from the bottom of the balloon, which most audiences wrongly identify as either smoke or steam. We then produce a large cloud of water vapour by adding dry ice to hot water containing universal indicator in a large conical flask. The indicator colour change is linked back to the fizzy drink and tooth decay. An additional activity is our mini version of the infamous Diet Coke and Mentos fountain demonstration, inspired by watching the originators of the YouTube videos, Eepybird, set off of 100 two litre Diet Coke bottles to music at the Newcastle science festival in 2009. Our scaled down version uses a 500 ml bottle so the foam rises to a height of less than 2 m, enabling it to be used indoors.

Moving on to crude oil, we then take washing-up liquid, makeup, candles and fleece clothing out of the basket. This is another example of items linked by their raw material and a great opportunity to discuss renewable and non-renewable resources. Many audiences do not realise the full range of common products that originate from crude oil. We link the fleece fabric back to the earlier drinks bottle via the recycling of poly(ethene terephthalate) (PET). This leads to the demonstration using the detergent to make the ever popular ‘elephant’s toothpaste’; decomposing hydrogen peroxide with a manganese (iv) oxide catalyst, complete with red and blue stripes. This usually wins the audience zapper vote as their favourite part of the presentation.

The four items that come out of the basket for the nitrogen experiments either contain nitrogen gas (crisp packet and squirty cream) or are produced using it (frozen peas and expanded polystyrene cups). Liquid nitrogen is used to commercially fast freeze frozen peas and this is the link into our demonstrations using liquid nitrogen. These demonstrations use the fact that most materials become brittle at this extremely low temperature and links back to one of the zapper questions in the first act on using properties to distinguish metals from glass.

The additional demonstration of the collapsing drinks bottle is particularly appropriate for KS3 or KS4 audiences where kinetic theory, air pressure, vacuum and balanced forces can be discussed.

Shopping basket items and activities

| Theme | Salt | Carbon dioxide | Crude oil | Nitrogen |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basket items |

Bleach Margarine Toilet rolls Soap |

Fizzy pop Chocolate cake Loaf of bread Decaffeinated coffee |

Washing-up liquid Makeup Candles Fleece clothing |

Packet of crisps Squirty cream Frozen peas Expanded polystyrene |

|

Activities Note: italicised |

Making ice cream |

Inflating balloons Making a cloud Mini Coke and Mentos Bubbles with detergent |

Elephant’s toothpaste |

Rubber tubing Frozen flowers Banana hammer Collapsing bottles Disposable gloves |

Act three: chemistry-related careers

This final act is again zapper based, with a series of questions consolidating the ideas discussed throughout acts one and two and linked to careers outside those typically envisaged for a chemical sciences graduate. This act is very popular with teachers because it makes explicit links between chemistry degrees and a wide variety of employment options that embrace the broad range of transferable skills that chemistry graduates acquire. This is something that schools often struggle to deliver due to time constraints linked to student performance targets. It concludes with two general feedback questions which demonstrate clearly that the overwhelming majority of students enjoy the session.

Flexibility is key

Although originally designed for years 5–9 (ages 9–14), the basket has proved to be a very versatile and flexible presentation as we have delivered it to audiences ranging from ages 4–84. The majority of our sessions take place in schools, however we have also delivered it in lecture theatres on both of our university campuses, museums, the International Centre for Life, Hexham Racecourse, Alnwick Gardens, a tent at a County Durham scout camp, various science fairs and festivals, a premier league football stadium (St James’ Park) and a county championship cricket ground (Chester-le-Street Riverside).

While the full version is 55–60 minutes, in order to deliver an interactive presentation at school careers events, with multiple 15–20 minute slots across the day, we also developed several shorter versions. These either remove one or more themes and some activities and/or reduce the number of zapper questions. It also does not have to be delivered as a formal presentation, as we sometimes take it to science fairs and run a drop-in stand using the shopping basket items and associated activities that can be demonstrated instantly. We also have infinite flexibility in the size of audience that can be accommodated – we are really only limited by the availability of sufficient zapper handsets. The smallest audience so far is five at a school science club and the largest is 300 year 8 students combined from two Northumberland middle schools.

In our extensive experience of delivering the basket, smaller (up to 40–50) audiences work better as there are more opportunities for a greater proportion to be involved in the activities. Larger audiences definitely benefit from ramped seating in the venue.

We were delighted at the end of our fellowship year when Chemistry in your shopping basket was added to the RSC’s Chemistry for our future website, especially as it is the only one developed by schoolteachers. The activity has also been adopted by the Alchemists, a group of chemistry postgraduates at the University of Oxford who deliver outreach activities in schools, initiated by Roger Nixon, another RSC school teacher fellow seconded there in 2009–10.

Participant feedback

In conclusion, the best advocates for promoting Chemistry in your shopping basket as an engaging, relevant and highly flexible resource are the audiences themselves, so here are a few quotes:

- ‘My favourite part was when they made the elephant’s toothpaste, it was cool the way it swirled around’ (primary school student).

- ‘They [Anne and Peter] have a fantastic rapport with both the children and staff. The pitch of their presentation and workshops fully engage, motivate and inspire the children, making them think about chemistry in everyday life as well as a possible career’ (primary school science coordinator).

- ‘This is serious fun – my students have seen it, both my children have seen it and I still try to sneak in to see it whenever I can’ (secondary school head of chemistry).

- ‘Instantly engages all pupils and presents chemistry in a real and meaningful context. A unique and original approach to scientific learning’ (primary school teacher).

- ‘This was a really great session that our Beavers still talk about and it also helped them to get their science badge’ (Beaver leader).

Peter Hoare is the chemistry outreach officer in the school of chemistry at Newcastle University. Anne Willis is a senior lecturer in chemistry and forensics in the school of life sciences at Northumbria University. Anne and Peter were both RSC school teacher fellows in 2008–9 and have continued to develop and deliver collaborative outreach across the region

Further information

- Chemistry in your shopping basket resources

- RSC Chemistry for our future resources

- Newcastle chemistry outreach

- Northumbria chemistry outreach

- Eepybird at the Newcastle science festival

- Alchemists at University of Oxford

No comments yet