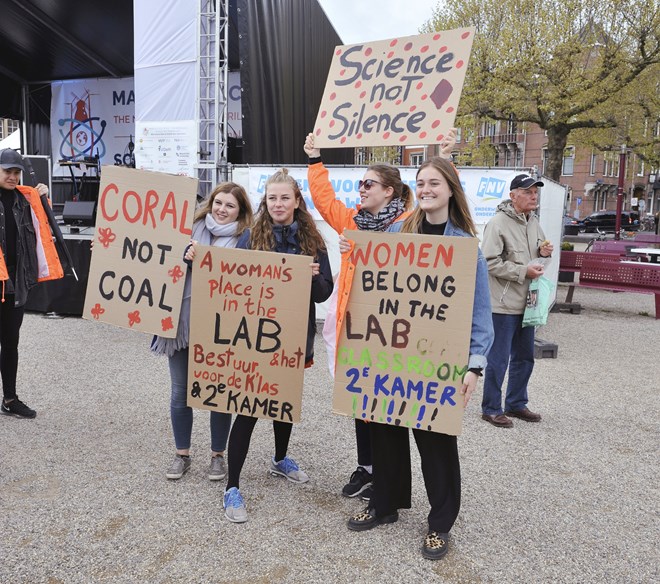

Lazy stereotypes and unconscious gender bias are putting girls off pursuing qualifications and careers in chemistry. Kat Arney discovers how schools could help reverse the trend

Across the UK, the number of people in the chemistry workforce is falling. In 2012, the Office for National Statistics estimated that the number of professionals in chemistry or allied fields was about 32,000 (of which about 10,000 were female). Five years later, this number had shrunk to just 24,000. The good news is that the proportion of women in chemistry-related careers is holding steady at about 30 per cent but, according to Keith Purves – a fellow of the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) and deputy chair of the board of Women in Science and Engineering (WISE) – this is a call to action rather than cause for complacency.

‘Science, technology and engineering drive progress in this country,’ Keith says. ‘Our members are very concerned about the loss of scientific talent, particularly in the light of Brexit, and the untapped female talent pool is potentially vast. Girls don’t have difficulty choosing bioscience or medicine – when you look at the statistics these subjects are over 70 per cent female – so what is it that girls find attractive about medicine and don’t find quite as attractive about chemistry?’

Over the years, many organisations have attempted to address this issue with varying degrees of success. Perhaps the most widely derided effort in this field was the European Commission’s ‘Science: it’s a girl thing!’ campaign in 2012, which dialled up feminine tropes to the max in an effort to entice secondary school pupils into science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).

The accompanying video, showing girls sporting lipstick and labcoats against an aggressively pink backdrop, was billed as an attempt to break down the stereotype of scientists as old, white men, yet all it managed to do was reinforce a different but equally tired cliché. Similarly, chemistry sets aimed at girls tend to focus on makeup and beauty products, complete with a heavy sprinkling of sparkles.

Unfortunately, attempts to entice girls into science by making it ‘girly’ are counterproductive. Researchers from the University of Michigan have shown that focusing on the femininity of female researchers actually decreases girls’ interest in studying science, especially if they dislike STEM subjects already.

Despite the fact that girls perform slightly better than boys in science subjects at GCSE level, including chemistry, there’s a significant drop-off in the numbers choosing to take their talent further. If we’re to encourage more girls to pursue chemistry at A-level and beyond, we need to know what’s putting them off – and it isn’t the lack of glitter.

Gender bias in the classroom

At the Institute of Education at University College London (UCL), Louise Archer and her team are running a long-term research project, known as ASPIRES, investigating the science interests and career aspirations of thousands of young people in secondary education. Although the study has found general predictors of the likelihood that a child will go on to study science post-16 (such as their exposure to science at home and whether they self-identify as ‘sciencey’) there is an intriguing observation that explains the stark difference between boys and girls. Put bluntly, girls simply don’t think that science is something they can do.

‘The thing that puts boys and girls off continuing with science, including chemistry, is this notion that it’s really hard and you have to be very, very clever to do it,’ Louise says. ‘We know that girls do well at science GCSE, but they still think they’re not good enough or clever enough to go on to A-level or university. And we see this attitude particularly in girls from working class and minority ethnic backgrounds.’

Louise is convinced that the lack of confidence girls have in their abilities stems from entrenched stereotypes and biases in the classroom and beyond.

‘There’s a persistent notion that the ideal student is assertive and confident, but while a white middle-class boy gets called assertive, the same behaviour in a girl might be interpreted differently and people will say that she is bossy,’ Louise explains. ‘We also see this with black students as well: speaking out and having a voice is seen as challenging or disruptive, and there are inequalities, biases and injustices that play into that.’

She also cites research in science classes where girls attain grades equal to or higher than boys’ grades, yet when asked to explain the outcomes teachers put the girls’ successes down to hard work and diligence. In contrast, boys are more likely to be described as having natural talent or flair for the subject, despite their lower grades.

Equality training for teachers

Tackling this underlying but pervasive sexism is a major challenge. Louise thinks the first step should be to educate teachers. ‘Teachers are people – they’re part of society – so why should we expect them to have a particularly nuanced understanding of the intersection of gender and ethnic inequality without any backup and support? I would love teachers to get a proper introduction into issues around equality as part of their training, which they don’t get at the moment.’

Equality training doesn’t just have to come at the beginning of a teacher’s career. The WISE campaign offers training for anyone at any time, including school staff, to identify and address unconscious biases. Campaigning group Let Toys Be Toys aims to end gendered marketing of children’s toys, books and clothes. The group has produced lesson plans for primary and secondary schools to help children identify and tackle the gender stereotypes that surround them.

The problems caused by entrenched gender stereotypes also explain why the ‘pink lipstick’ approach does little to entice girls into chemistry. ‘We know from the research we’ve done that science tends to be associated with masculinity and there’s a snobbishness that says you’re not serious or intellectual if you’re girly,’ says Louise. ‘On one hand there’s value in broadening the notion of what makes a scientist – if you want to be a girly girl and work in chemistry that should be fine. But the flipside is that it plays into a really narrow stereotype of what femininity is: either you’re serious or you’re girly and there’s nothing else. It’s all aimed at the problem being in the minds of the girls and not the culture and structures more widely.’

Matching pupils’ interests

Louise is also keen to see science teaching methods change, including more personalised lessons tailored to the true interests and values of pupils of all genders, helping young people see that science is ‘for them’ and part of their lives. ‘They get a lot of content but if you don’t get the relationship with science right, then young people will just not see the point of it,’ she says.

One campaign aiming to address the problem is WISE’s People Like Me, launched at the British Science Festival in Bradford in 2015. WISE’s campaign is principally aimed at addressing the reasons why girls don’t choose to take up physics at A-level, but is also relevant to the shortfall in chemistry. The idea is based on social science research showing that girls tend to see themselves in terms of what they’re like, using adjectives such as ‘friendly’ or ‘talkative’ to describe their interests and personality, while boys tend to use verbs to describe what they do.

Aimed at girls aged 11–14, the programme helps students match their self-described strengths and interests against a list of 12 ‘scientist types’, ranging from explorers – who might typically work in research labs – to regulators, communicators and managers. The idea is to show the breadth of career opportunities in science and the types of role that a girl could fit, if she chose to take her interest further.

Chemistry for all

However, it would be a mistake to put the burden of change solely on teachers and girls – there are other approaches that can boost female interest in chemistry. Tamjid Mujtaba at UCL’s Institute of Education is evaluating the £1 million Chemistry for All project, funded by the RSC and running over five years. Universities in three areas across the UK are delivering chemistry-based activities for around 4000 local schoolchildren, including hands-on practical sessions and after-school chemistry clubs, talks about careers involving chemistry, and visits to companies working in relevant industries.

Similarly to Louise Archer and the ASPIRES team, Tamjid has found that although many girls in the study had a positive perception of science – understanding that it’s important and expressing an interest in carrying on post-16 in scientific subjects – they still had low confidence in their own abilities. Although the Chemistry for All activities are mixed gender (unless attended by students from single-sex schools), Tamjid and her team have found that the programme is making a significant impact on girls’ confidence and belief that chemistry is something that they can do.

‘What this project is showing is that the girls who have engaged in extracurricular activities are more likely to express the desire to carry on with chemistry after the age of 16,’ she says. The more of these activities the students experience, the greater the increase in their interest. The cohort of students haven’t yet got to the point of making A-level choices, but Tamjid is hopeful that students’ interest will translate into an increased number of girls taking the subject. ‘We’re really impressed with the findings so far. Even if they’re not going to continue with chemistry, they still think it’s more interesting than before and that’s really encouraging.’

The impact of extracurricular activities seems to over-ride other external influences such as low socioeconomic status or a lack of exposure to science at home. ‘I was surprised to see that access to these activities has a bigger effect than social class or family background. What it tells us is that these things matter less than support and encouragement – saying to girls “you can do this!”’

Tamjid’s work also highlights how gender bias in the classroom creates a toxic environment that prevents girls from acting on their interests in science. By giving girls space to contribute to classroom discussions and engage with hands-on activities, teachers can help girls to feel they belong in the chemistry classroom as much as boys do.

All together now

While most approaches aimed at encouraging female participation in STEM have focused on girls, Louise notes that boys shouldn’t be ignored.

‘Everyone seems to think we can just leave the boys to it, but sexism gets perpetuated by everybody,’ she says. ‘Speaking as a feminist I would like more explicit feminist politics and education for girls to build their confidence, but we shouldn’t let any young people leave school without exploring issues around racism, sexism and gender. I hear boys saying quite stereotypical things that girls would never say, and boys do dominate the teacher time – they see science as their subject – so we should not forget that they are part of the picture too.’

Finally, there’s a role that everyone in chemistry can play to address gender imbalance and encourage more girls into the field. Keith Purves points out that there are more than 20 professional bodies for engineering, brought together under the national umbrella of EngineeringUK to raise the profile of the sector. More than 70% of the growth in the engineering workforce over the past five years has been women, so they’re clearly doing something right. Keith believes a similar team effort from the world of chemistry might also bring dramatic results. ‘You can change the world with chemistry, but that message just isn’t getting through. Everybody understands the dimensions of the problem, we just don’t know how to effectively knock down barriers or inform the right people in the right way so that it sticks. If we all join hands and work together it would be wonderful.’

Further reading and resources

- The ASPIRES project: rsc.li/EiCASPIRES

- WISE unconscious bias training: bit.ly/2Dt04RX

- Free lesson plans by Let Toys Be Toys: lettoysbetoys.org.uk/lesson-plans

- The Chemistry for All project: rsc.li/EiC-c4all

No comments yet