Practical research projects are vital in the training of the next generation of forensic scientists, explains Matthew Almond

Final year research projects are an important part of undergraduate chemistry courses, allowing students to enhance transferable skills in teamworking, problem solving and presentations, at the same time as learning valuable practical skills.

Several recent reports have highlighted the importance of research based studies as part of undergraduate courses. ‘We need to encourage universities to explore new models of curriculum. They should all incorporate research based study for undergraduates to cultivate awareness of research careers, to train students in research skills for employment, and to sustain the advantages of a research teaching connection,’ wrote Paul Ramsden from James Cook University, Australia, in a 2008 report for the UK’s Higher Education Academy.1 A 2010 report published by the Biopharma Skills Consortium – that promotes collaboration across the higher education sector in the area of biopharma – also stated that: ‘Companies seek recruits well placed to acclimatise quickly to the work environment. They are looking for recruits who can deploy a range of generic skills in the application of their knowledge.’2

Reading the evidence

Chemistry with Forensic Analysis is a popular undergraduate BSc degree course at the University of Reading, UK. However an increase in student numbers due in part to the popularity of TV programs like CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, coupled with a lack of teaching staff, has meant that individual final year research projects in forensic analysis have become impossible.

In 2007, the department was awarded funding to set up a series of team mini projects to be carried out in the third and final year of the course. The funding came from the Higher Education Academy’s CETL-AURS (Centre of Excellence for Teaching and Learning – Advancing Undergraduate Research Skills) that is based at the University of Reading. The mini projects let students experience research in forensic analysis first hand, obtaining an in depth understanding of modern analytical techniques, while developing their teamworking skills and undertaking independent open ended study.

Putting theory into practice

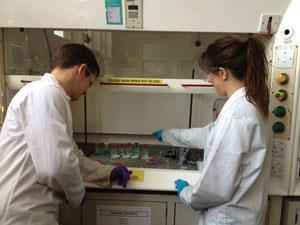

The groups consist of three or four students, with one appointed as team leader to coordinate the group’s work. Wikis are set up to support interaction of the group members and for them to submit their final report. Typically 10 to 15 students carry out these projects each year.

The projects are designed to be completed in 20 hours of laboratory work with approximately 80 more hours of input including planning, background reading and report writing. The team are marked on both their final report and a group presentation. This mark is then adjusted within set limits (up or down 15%) to give an individual mark to each student on the basis of observation of their work in the laboratory, and their contribution to the team’s report and presentation. The wiki allows student activity to be monitored closely both in terms of contribution to discussions, interpretation of data and report writing.

Peer assessment was considered when the programme was set up but it was decided that for the small cohort of students involved it was not necessary. Peer assessment is notoriously contentious among students.3 In other modules at the university, where we have larger cohorts carrying out teamwork, peer assessment is used.

Topics under the microscope

The projects vary each year with topics so far including the analysis of blue paints by infrared spectroscopy, monitoring the ageing of fingerprints, investigating interferences in blood tests from foodstuffs and household products, and identifying lead crystal glass samples by lead isotope ratios. These are all important topics for real life crime investigation.

For the analysis of paints, for example, the students produced a database of IR spectra and elemental analysis of a series of visually similar paints identifying the pigments and resins contained within them. At the end of their project they devised a dummy forensics case with blue paint found at a crime scene and traces of the same colour paint found on the hands of four suspects. Infrared spectroscopy and elemental analysis was carried out on each sample to identify the guilty party.

In the second example, the ageing of fingerprints, two fingerprint enhancement methods were studied: cyanoacrylate fuming and electroless copper deposition. The team of students decided that two people would carry out a method each, and the third person would analyse and process results. However, before the results could be analysed, each fingerprint needed time to age from 24 hours to six weeks. This had to be scheduled into the time plan. This group was highly organised; tasks were scheduled for each week and at times when no laboratory work was required (due to the ageing of fingerprints), literature research and the project write up began. This project has led to published work.4

Wrapping up the case

These forensic mini projects have very strong student satisfaction. Typical comments from participants have included: ‘The project was extremely enjoyable and a great way to get some more practical forensics into the course.’

The cohort of students each year has been too small to carry out any meaningful statistical analysis of data on marks achieved. However, two general points emerge. The first is that there is a strong level of graduate employment among the students who have taken these projects – most commonly in the analytical chemistry sector.

Secondly, the students who carry out mini projects generally show an enhanced academic performance when compared with their colleagues studying BSc Chemistry who have not taken this module. In one year there were 10 Chemistry with Forensic Analysis students (who all took the mini projects) and 15 Chemistry students who did not. The former group of students increased their overall marks from an average of 60% at the end of their second year to 63.5% by the end of the course. By contrast the marks for the Chemistry students remained constant at 59%. Admittedly these are small increases for small numbers of students and are not statistically significant but carrying out these mini projects does appear to lead to a general improvement in student performance overall, probably by increasing confidence.

This programme has achieved its aim of improving students’ laboratory and general academic and transferable skills while enhancing their employability. It is also very enjoyable for both students and supervisors. This model is highly recommended to others.

Imogen McCarthy and Imogen Payne offer the students’ point of view

We both carried out a mini project in 2012 studying the degradation of fingerprints on brass surfaces, during the final year of our degree course at the University of Reading, UK. The capability to work in a team is a desirable skill which many employers look for evidence of when recruiting. It is important therefore for university students to experience this to prepare for job hunting and future employment.

This forensic mini project gave us the chance to work productively with others, learning from each other and also realising the advantages and disadvantages that come with working alongside other people. Teamwork means having to negotiate workload, being able to communicate at all times with other members and being organised in order to be as productive as possible within given time restrictions.

Planning ahead

Before literature research and laboratory work began, we had to construct a plan. This provided personal deadlines for each member and gave a timescale of how and when work should be carried out. With a time restriction of only four weeks, this plan was all important to the success of the project. It was the team leader’s responsibility to make sure that each member of the group was organised; they knew what tasks they were doing and when they needed to be completed by. Good teamwork was also required in the laboratory.

During the project, our team had to overcome a particularly difficult obstacle when one member of the group withdrew from university. This meant we had to adapt and rearrange our workload and redistribute the work. Although this may be looked upon as a disadvantage, ultimately it was an additional challenge that tested our skills even more.

Assessment

We were assessed as a group with slight alterations made to individual marks where it was deemed necessary. This method of marking was good as it took into account the teamwork aspect. However, there is always an issue with how much each team member has contributed. For example, some team members may have done more work than others that had gone unnoticed, such as library research or results processing.

Overall, the members of our team were happy with the way the group was marked. However, in our particular case there was good communication and organisation between the students and supervisor. It is possible that in other cases the share of work would have been less well divided, and communication could be poorer, resulting in less accurate group assessment.

The wiki page

Throughout the project, the whole group, including our supervisor, had access to a wiki page. This could be edited by all team members and allowed us to share ideas. The original introduction to the project and all the planning was posted on this site. Reference sites and articles relevant to the project were also listed, so that research and the write up of the project became more time efficient. This was the collection base of all of our submitted work throughout the project and meant that our progress and the distribution of work between the group could be monitored.

On reflection, we found the wiki page to have both advantages and disadvantages. Although it was a good foundation to analyse who was writing which sections of the final write up and also how much they were writing, it did not give any indication of any of the other types of work that were going on behind the scenes that could in many instances consume hours of time. For example, collating and editing of photographs and compiling them to fit effectively into a presentation. This was a very time consuming task that, if left to the wiki page alone, would have gone unnoticed. Hours of reading time were also spent in the library studying journals and books. The writing up itself was probably what took the least amount of time.

Working together

There are several potential disadvantages to teamwork. In our case, one team member dropped out. Although this is rare, in general within teams it is often found that not all members pull their weight. Assessment of a team is fairly difficult and it is impossible to monitor everyone all the time. A lot of the work is done away from the lab and isn’t always documented on the wiki page and so assessment based solely on something like a wiki page could be unfair. One member may get a higher mark purely because they have posted more documents online, when in reality, it doesn’t necessarily mean they have done more work.

Peer assessment is often used to assess the input of individual team members. However, it only works well if organised carefully. Problems may arise, for example, if the peers assessing each other are close friends; they may not be entirely truthful as to how well they have all worked as a team and to how much work has been done. Of course this sort of dishonesty may be noticed by the supervisor when assessing a final write up due to lack of content. On balance we were happy that peer assessment was not used for our project.

There are, however, many advantages to working as part of a team rather than individually, especially because the project was lab-based. We found a lot more laboratory work could be carried out in a much smaller amount of time by a team, meaning we could explore many more different research areas. Group discussions were also very beneficial as these allowed members to collate their ideas about the results and led to a deeper understanding of the chemistry. Literature research was also much more efficient too.

Acknowledgement: With thanks to John Baum, a senior laboratory technician at the University of Reading, UK

Matthew Almond is a professor of chemistry education at the University of Reading, UK Imogen McCarthy and Imogen Payne are both graduates in Chemistry with Forensic Analysis from the University of Reading, UK. Payne is now employed at Afton Chemicals, Bracknell, and McCarthy at CEM Analytical Services, Ascot.

References

- P Ramsden, The future of higher education teaching and the student experience. The Higher Education Academy, 2008

- South East Universities Biopharma Skills Project, Final report. University of Reading, 2010 (http://bit.ly/145v0O4)

- S Loddington, Peer assessment of group work: a review of the literature. University of Loughborough 2008

- I C Payne et al, J. Forensic Sci., 2014, accepted for publication

No comments yet