How to steer perfectionism in the classroom in positive ways

Perfectionism is a common issue in the chemistry classroom for teachers and pupils. It can manifest in a number of ways and typically takes three forms: self-orientated (‘I must do this right’), other-orientated (‘they must do this right’), and socially-prescribed (‘it is expected of me to do this right’).

- Self-orientated perfectionism is the easiest to spot: a student who rejects anything that isn’t perfect, which often leads to disappointment. Self-orientated perfectionism can also be subtler. Students who avoid – by not handing in work on time, not completing tasks, and seemingly not engaging with lessons – are often hidden perfectionists. These students hide to avoid facing the reality of imperfection.

- Other-orientated perfectionism is evident in students who quickly become frustrated during group practical work because they want their team to carry out everything correctly. They frequently ask questions and seek clarification, then return to their team to say ‘I told you so’. This type of perfectionism is common in adults too – the frustration a teacher can feel with a class who don’t get it.

- Socially-prescribed perfectionism presents in students who feel a lot of pressure from their parents or carers; they feel a poor result could lead to anger or disappointment. It is important as a teacher to recognise that this type of perfectionism can result from our relationships with students too – a student may feel they have let you down with poor performance or lack of understanding, and may behave negatively in lessons.

Turn perfectionism into a positive

Although we need to encourage students by setting high standards, these standards must be achievable. The key to combatting perfectionism is to recognise that it can also be a useful tool in learning. Negative perfectionism mainly arises when goals are unrealistically high or vague.

As a teacher, it is important to recognise the positives and negatives and encourage students, rather than saying ‘stop being a perfectionist and get on with it’. By reframing perfectionism, you can help students to apply its more positive aspects to their work.

| Examples of negative perfectionism | Reframing for positive perfectionism |

|---|---|

|

Belief that one should or must excel |

Desire to excel/succeed for yourself |

|

Focus on avoiding all errors |

Careful attitude towards work |

|

Large gap between performance and standards set |

Set high attainable standards for performance |

|

Sense of self-worth dependent on performance |

Sense of self-worth dependent on the process of learning |

|

Failure associated with harsh self-criticism (conditional self-acceptance) |

Failure associated with disappointment and renewed efforts |

|

Inflexibly high standards |

Standards modified to suit situation |

The key to tackling negative perfectionism is to recognise events that trigger this behaviour. Being able to pre-empt such times can help in setting realistic expectations to better support students. Get to know the perfectionists in your classroom – do you notice particular stressors, for example giving presentations, doing practical work, handing in homework, giving back tests? Once you have identified the cause, or activating event, you can apply the ABCDE model.

The ABCDE model

Activating event – What is the root cause of the habit?

Belief – What is the unhelpful thought that the student has?

Consequence – What will be the result if the student continues to think this way?

Disputing argument – How can we rephrase/set clearer expectations for the student?

Effective way forward – What steps should we encourage the student to take?

For example: (A) a student gets an unexpectedly low result in a test. (B) They then believe they are ‘rubbish’ at chemistry, and ‘can’t do it’ even though they tried. (C) Their confidence drops as a result, they feel demotivated, and spend less time in future revising for tests because they believe it didn’t help last time. (D) By talking to the student, you can reassure them, putting their result in the context of their progress – perhaps it was a hard test. Highlight positive aspects of their test paper and focus on their strengths. (E) Perhaps the student would benefit from further practice, so you give them some past paper questions and mark schemes to review.

Be open with your students about this process. All too often when I return tests, I give no space for students to let out their negative feelings. But space to catastrophise and verbalise feelings can be a very useful process to help you understand your students better and help them to recognise how they could modify their behaviour or thoughts, and enable you to suggest effective ways forward.

Reconsider the way you give feedback

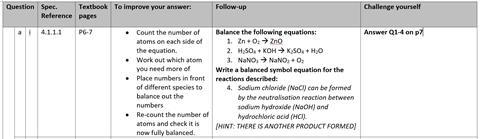

Once you have identified unhelpful thinking errors, you can support your students to adapt through rephrasing. I recently trialled gradeless marking in tests. Such tests are not entirely gradeless, but I have changed the focus of my marking. Rather than returning tests with a simple percentage on the top, I first return tests with dedicated improvement and reflection time (DIRT) sheets to help point students in the right direction to improve their work. Vital to this strategy are the ‘Challenge yourself’ questions below. These send the message that there is always room to learn and improve, even if you achieved 100%. If you only run through mark schemes, more work is given to the students who underachieved, which reinforces the negatives.

In addition, rather than reporting percentages and medians, I encourage my students to compare themselves with themselves, by noting at the top of their work whether they are ‘on track’, ‘working below my target’ or ‘working above my target’. This system has changed the way my students respond to feedback, and has reduced the number of ‘justifications’ I get (I didn’t revise because …). It makes the atmosphere more purposeful and less judgemental.

Encouraging students to set SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Timely) targets is crucial to get them to make the most of their time, particularly when it comes to revision. This year I dedicated a whole lesson to showing my exam classes what I actually expect them to do when they revise. All too often a student’s idea of revision is very different to mine. By taking time to lay out SMART strategies you can avoid students overworking themselves or procrastinating.

None of the above strategies will work overnight. The tenacious attitudes of students can be difficult to shift, but by gradually working through these techniques, you too will hopefully see a big improvement in your students’ motivation.

1 Reader's comment