- Podcasts can be an effective tool to augment and facilitate student learning

- Feedback given as a podcast includes the richness of the voice which written text lacks

Podcasts and podcasting

A podcast is an audio file which can be played on a computer or any portable device such as an iPod or any other MP3 player. Podcasts are usually considered to mean just audio format, although the term is sometimes used to mean audio and visual format - for example annotated class notes or screen-capture videos - but these are more correctly called screencasts. Podcasting is the process of recording these audio files and making them available. It is now very easy to record and distribute podcasts for educational purposes, and in the last few years, there has been a surge in the number of literature reports on podcasting.

Podcast catagories

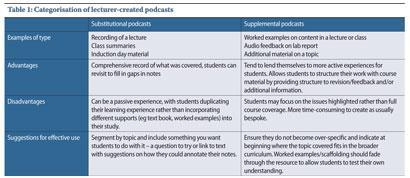

One useful classification of educational podcasts (and screencasts) categorises them as substitutional and supplemental.

Substitutional

Substitutional podcasts are those which essentially replicate what is done in class time. These aim to provide students with a second chance to hear the material again so that they may recover a difficult topic, note something down that was missed the first time, or if a lecture was missed, go over the material in their own time.

They have seen a meteoric rise, as they are relatively easy to record in tandem with live delivery and provide a sense of security to students that all of the material covered is available on their virtual learning environments at any time. However, research studies into the

use of substitutional podcasts highlight that, despite intentions to do so, students do not use them much. When they are used, only small parts of them (usually areas of difficulty) in the run-up to exam time are listened to. This leads to the second categorisation of podcasts: supplemental podcasts.

Supplemental

Supplemental podcasts aim to provide additional material or support to what is given in class time. For example, a podcast may cover an area of difficulty, provide some worked solutions to questions and prompts towards solving additional problems. In this way, supplemental podcasts are tuned to specific difficulties or areas of feedback in the curriculum, rather than try to cover all of it again. Substitutional podcasts tend to mimic the passive experiences of a class - a student listens while the teacher talks - whereas supplemental podcasts tend to mimic tutorials - providing additional information, prompts and guidance. Supplemental podcasts take more time and effort to create, but it appears from literature reports that they are a more effective instructional tool for enabling student learning.

Why use podcasts?

As podcasts can be listened to at any time, in any place, many of its proponents argue that they offer an increased level of accessibility to learning materials. While there is no doubt that in principle, they do, many studies to date report that students still listen to podcasts at their desk during time they have formally assigned to study.

A more promising argument in favour of podcasting is that they afford an opportunity to enhance student learning. By augmenting material given in classes, podcasting allows students to recover material (substitutional podcasts), to address material in a more active way (supplemental podcasting), or to hear feedback on work completed incorporating the richness of the tone of voice that written text lacks. Podcasts designed to actively assist study of a module provide a useful resource to students, and as it is a resource featuring the module teacher with his/her tone and emphasis implicitly imparted through audio, it lifts its value out of the plane of many other generic course materials.

From a teacher's perspective, resources can be made reusable from one year to the next with some consideration, and therefore a bank of resources to help structure students' study and revision of a module can be created over a few years. Feedback, particularly group feedback, can also substantially save on time when compared to written equivalents.

Creating a podcast

Technically, podcasts are now very easy to make. It is possible to record podcasts on a smartphone and email them directly to students. The most common approach however is to use the free software Audacity, which can be downloaded from the website (see the link on this page). Audacity is an audio recorder and editor and audio files can be created and easily edited.

The video at the end of this article shows you how to download Audacity to your computer and set it up correctly to record your podcast. It also shows you how to do some basic editing.

There are several tutorials on the internet about using Audacity. In order to record, you will need a microphone. The quality (and price) of these varies, but a simple headset microphone (about ?20) will produce files of good quality.

Tips for success

Things to watch out for when recording include:

- keeping the microphone piece just below your mouth to avoid the force of your breath causing bumping noises

- avoid banging the wire from the headset to the computer

- avoid tapping or banging the desk when speaking!

All of these noises are greatly amplified in a recording and can be irritating to listen to.

The greatest bugbear of audio recording is background noise. This can vary from a computer fan to outdoor traffic. While it is possible to reduce noise in Audacity, it never quite works as you would hope, so it is advisable to record in as quiet a place as possible. Once recorded, files can be exported as an MP3 file, which is a compressed audio file balancing good audio quality and small file size.

Structure

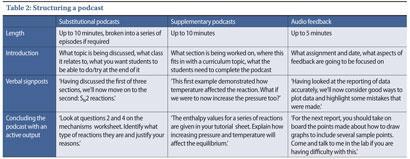

Technical issues considered, it is now possible to start recording. Depending on the type of podcast you wish to create, the structure, length, and tone may differ. However, in all cases, there should be a clear introduction highlighting what is going to be covered (including an assignment reference if it is audio feedback), what is needed while listening to the podcast (notes from the class, a returned assignment, a book) as well as verbal signposts at subsections within the podcast so students can tell where they are in the sequence as they listen. This is important, as a disadvantage with audio is that scanning through it is not as easy as scanning over a text document to find the bit you are interested in.

The podcasts should finish up with what you want the student to do based on what they have just listened to; try a question, read a textbook section, re-draw a graph. It is generally recommended that podcasts should be no longer than 10 minutes (approximately 1000-1500 words) and no longer than five minutes for podcasts for feedback. Longer podcasts should be broken up into sections.

Substitutional podcasts created purposefully (ie not recorded in parallel with live classes) lend themselves to being more formal in tone. Scripting is a personal preference, but I have found that time gained not writing a script is easily lost on making several retakes. With scripted podcasts, it is tempting to take on a broadcaster tone. However, one great advantage of podcasts from students' point of view is that they are given by their teacher, so tone should be similar to that used in class. A supplemental podcast may not need to be as rigidly scripted, as the activities themselves within the podcast will drive the narrative; the tone here tends to mimic that of a tutorial.

Limitations

Podcasts, like any learning resource to support teaching, are not without their limitations. The most obvious question for a visual, representational subject like chemistry is whether audio is suitable at all. Indeed podcasting is often the first step to screencasting. The choice can probably be made in how it is used. Discussing an organic mechanism in a complicated molecule would be difficult using only audio. It would probably be necessary to refer to a visual, or use screencasts in place. But audio files could have a place in discussing more big idea issues such as reactive sites in various functional groups.

It is a different skill to explain something verbally than to do so in written form, and the latter is often under-represented in our curricula. As such, there is a place for podcasts in the suite of resources we present to students, and there is a growing body of evidence to suggest that it is empowering and enhancing student learning.

Michael Seery is a lecturer in physical chemistry at the Dublin Institute of Technology.

Further reading

- G Salmon and P Edirisingha, Podcasting for learning in universities. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press, 2008

- O McGarr, Australas. J. Educ. Technol., 2009,25, 309 (pdf)

- Sounds good project, audio feedback guide: https://sites.google.com/site/soundsgooduk/ (accessed 17 January 2012)

No comments yet