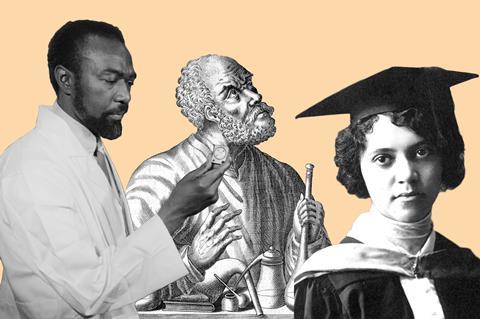

Find out how chemists at Queen Mary University of London can help you to include the contributions of BAME scientists in your chemistry classroom

It was a cricket commentary that inspired Tippu Sheriff to tackle the lack of non-White faces included in the UK secondary school science curriculum. Rain had stopped an evening match, he explains, and the radio commentators filled time by discussing the floodlights above them. One said that although we are all taught at school that Thomas Edison discovered the light bulb; his device didn’t actually work very well. ‘It was Lewis Latimer, a Black American inventor whose parents were slaves, who developed the carbon filament that made the light bulb a useful device,’ he said.

For Tippu, a senior lecturer in chemistry at Queen Mary University of London (QMUL), this was an eye-opening moment. He was suddenly acutely aware that Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) contributions to science are almost entirely omitted from the school curriculum.

Surveying secondary science teachers

Together with departmental colleague Lesley Howell, Tippu applied for a Royal Society of Chemistry inclusion and diversity fund grant, to look at ways to fix this omission. They recruited two second-year QMUL chemistry students – Aisha Sharif and lsrat-Zahan Chowdhury – to help them on their project.

The team developed an online survey and recruited around 200 secondary science teachers and A-level students to complete it. They were asked if they thought Black, Asian and minority ethnic scientists were adequately represented in the national curriculum. Over 90% of participants said no. The survey also asked if they had heard of some important historical scientists. ‘About 92% said they had heard of Thomas Edison but only 28% had heard of Lewis Latimer,’ says Aisha.

The team used a simpler version of the survey at a family science festival held at QMUL in June 2021. The results were similar: 86% of participating visitors had heard of Edison and 18% Latimer.

If some teachers had pointed out some role models of people like me contributing to science it would have helped my confidence

Tippu is hopeful that eventually the national curriculum will be changed to better reflect scientific contributions from BAME researchers. ‘It’s going to be a slow process getting policy changed,’ he predicts.

But schools don’t need to wait. They can start unveiling the hidden faces behind the chemistry curriculum for their pupils now. This isn’t about teaching entire new topics, just taking the time to mention some currently omitted names while teaching curriculum content.

Where to start

Here are a few ideas to guide you in including Black, Asian and minority ethnic scientists in your teaching:

- Read about the benefits of boosting awareness of BAME scientists. Two good starting points are The missing colours of chemistry in Nature Chemistry and UK chemistry pipeline loses almost all its BAME students after undergraduate studies in Chemistry World.

- Start small. Make one change to your teaching content, see how it goes, build up your confidence and then do more and more.

- Download the Highlighting minorities in chemistry resources developed by QMUL resources.

- If you develop your own resources, share them – via Twitter or Twinkl.

- Start looking around for other stories of marginalised chemists who could add value to your curriculum. The Chemistry World Significant Figures column is a good place to look, and you can also find profiles of scientists working today in A future in chemistry. For example, Taryn shares the barriers she overcame on her journey to working as a scientist in food and pharmaceuticals.

Developing classroom resources

The QMUL project team has identified areas in the chemistry A-level curriculum where contributions from historical BAME scientists could easily be slipped in and have developed classroom resources to support this. The resources include fact sheets for educators, classroom posters, videos and student worksheets. For example, a worksheet about Jabir Ibn Hayyan, an 8th century chemist, has students label the diagram of the distillation apparatus and contains an information box about his role in developing the apparatus.

The team has developed resource packs about Alice Ball (the African American chemistry professor who developed a treatment for leprosy), Walter Lincoln Hawkins (a Black polymer chemist who invented long-lasting coatings for telephone cables) and James Andrew Harris (a Black chemist involved in the discovery of elements 104 and 105).

Tippu has recently been awarded a second grant – by QMUL’s access fund – to develop school resources to highlight the German-Turkish couple that developed the Pfizer-BioNTech Covid-19 vaccine.

For Tippu, this isn’t just about raising awareness for fairness sake, it’s about letting school children see that people like them can be successful scientists. ‘I would have liked to have had those role models growing up,’ he explains. Tippu’s family originated from India and Tippu and his sister were in British army schools in Libya and Cyprus before coming to the UK in 1972. ‘When I was a teenager, if some teachers had pointed out some role models of people like me contributing to science it would have helped my confidence,’ he adds.

Decolonising chemistry teaching and learning

Start a conversation in your school with these articles and tips

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Include BAME scientists in your teaching

- 6

- 7

- 8

No comments yet