Get your learners to prove they understand and can construct a hypothesis with this fair test – complete with variables

Science is all about discovery. However, this is not always the case in science education. While teaching science through discovery isn’t effective, teaching students skills to work scientifically, such as how to construct their own hypothesis from some simple observations, is important.

Teaching this can sometimes be problematic. Students find it hard to come up their own hypothesis, often because they lack the necessary knowledge of the topic and what a hypothesis is. I find that explicitly teaching how to construct a hypothesis helps my students.

Introducing the idea of a hypothesis

Previously when I taught the idea of constructing a hypothesis, I started with a definition of what a hypothesis is. Now, thanks to Adam Boxer’s alternative approach in his book, Teaching secondary science, I prefer to leave the definition until after demonstrating what a hypothesis is, with a concrete example.

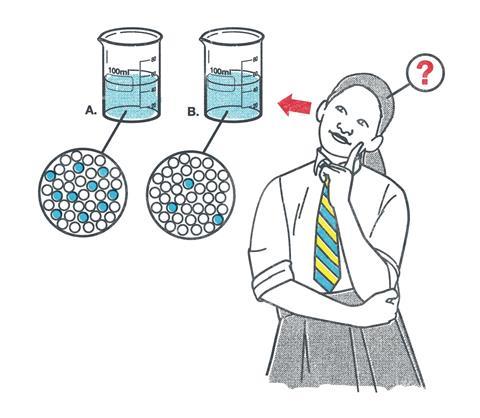

The example does not need to be complex. I prefer to use a simple rate of reaction experiment, such as dropping some magnesium in to a test tube of acid. I start with one concentration and one piece of magnesium. I ask students to turn to each other and talk about things I could do to make it effervesce more. They suggest a range of ideas and I pick one. I always pick concentration. We then discuss how we will know which concentration is better. I keep this qualitative as I want to make it as simple as possible. We discuss what concentration means and I draw two particle diagrams, one of a low concentration and one of a high concentration. I ask students whether they think a low or high concentration will be faster.

Download this

Candle investigation, for age range 11–14

Get learners developing a hypothesis and planning an investigation with this classroom activity.

Download the slides from the Education in Chemistry website: rsc.li/3DcMcvp

Defining it

I write the hypothesis on the board while explaining in detail to the class what a hypothesis is. My modelling goes something like this: ‘We have decided to look into how changing the concentration affects the rate of reaction and we think a high concentration will be faster because there are more particles. Let’s write that down. This sentence explains what we think will happen and why. These types of sentences are very important in science. They are the foundation of all experiments. We call this sentence a hypothesis.’

Having established what a hypothesis is, you can use this example to specifically teach all sorts of skills for working scientifically. You can introduce the language of variables and the concept of fair testing.

Developing it

To allow students to develop their own hypotheses, it is worth starting with very narrow options. Help them to curate their initial hypothesis using two-part multiple choice questions. These allow students to decide from a very limited range the cause and effect needed for the hypothesis.

To allow students to develop their own hypotheses, it is worth starting with very narrow options. Help them to curate their initial hypothesis using two-part multiple choice questions, as described in the article, ’Strategies to boost learning in practicals’ (rsc.li/3GChGMF). These allow students to decide from a very limited range the cause and effect needed for the hypothesis.

Over time, you can increase the variety of options before opening it up for students to write their own. Even at this stage, I would not expect students to be completely independent. You can use mini whiteboards to get students to suggest and record variables that could be changed. Then ask them to pick from this list and construct their hypothesis. I would get them to do this on mini whiteboards too, as the stakes are lower. I then find great examples and share them with the class to support those who are struggling to understand.

Recommended reading and resources

- Use research-based tips to help learners form scientific questions.

- Discover ideas for open investigations where learners can practise developing hypotheses with activities from In search of solutions.

- Explore the reactivity series of metals and displacement reactions with these experiments and videos for 14–16 students, use the pause-and-think questions to discuss what is being tested and why.

- Find out how senior principal scientist, Misbah uses computers to help make and test predictions about catalysts.

- Use research-based tips to help learners form scientific questions: rsc.li/3CWPLpn

- Discover ideas for open investigations where learners can practise developing hypotheses with activities from In search of solutions: rsc.li/3ZVG44G

- Explore the reactivity series of metals and displacement reactions with these experiments for 14–16 students: rsc.li/3HgA2Et

- Watch these practical videos with your 14–16 learners and use the pause-and-think questions to discuss what is being tested and why: rsc.li/3QNxlgx

- Find out how senior principal scientist, Misbah uses computers to help make and test predictions about catalysts: rsc.li/3wcBj99

When to teach about the hypothesis

Not all topics are well suited to teaching about the hypothesis. I am in favour of introducing it for ages 11–14 in topics to do with reactivity and displacement reactions. It is always preferable to map out the deliberate teaching of working scientifically skills. I like to map this in each year to ensure students get a chance to revisit it regularly.

Having a deliberate focus on what skill you want to develop in each practical is the most effective use of practical time in the lesson. This builds the skills and confidence students need to be successful scientists.

This article is part of our Teaching science skills series, bringing together strategies and classroom activities to help your learners develop essential scientific skills, from literacy to risk assessment and more.

No comments yet