Help your students with these solutions for murky science language

Recently, there has been an increased focus on the importance of literacy and language in science education. A guidance report published in 2018 by the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), Improving secondary science guidance, highlights the need for teachers to develop scientific vocabulary and support pupils in reading and writing about science. Literacy and language development in secondary school is often seen as the responsibility of English teachers. This report opens up the debate on why science teachers need to explicitly teach scientific vocabulary and develop students’ ability to read and write proficiently about science.

Recently, there has been an increased focus on the importance of literacy and language in science education. A guidance report published in 2018 by the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), ‘Improving secondary science guidance’, highlights the need for teachers to develop scientific vocabulary and support pupils in reading and writing about science (rsc.li/3aIFopb). Literacy and language development in secondary school is often seen as the responsibility of English teachers. This report opens up the debate on why science teachers need to explicitly teach scientific vocabulary and develop students’ ability to read and write proficiently about science.

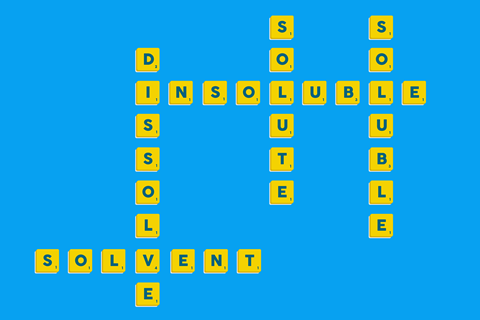

Many students struggle with the vocabulary needed to make meaning of science. This first struck me when, as young teacher, I was tasked with writing keywords lists for KS3 science (ages 11–14). I collated thousands of words into lists and realised these ‘new’ words could be overwhelming for students. For example, the keywords included as part of the topic of solutions, usually taught in year 7 (age 11–12), can include any or all of the following:

dissolve - solvent - solute - soluble - insoluble - solubility - solution.

Looking at the list, you would assume that 11-year-olds should know the meaning of almost all the words, possibly with the exception of ‘solute’. In this case, ‘know’ means recognise and understand the scientific meaning of each keyword. So how can teachers ensure that students have a scientific understanding of key terms in a topic?

Consider the keywords

Carefully review the keywords needed to make meaning of the science in the topic.

- What keywords would the students probably already know, eg ‘dissolve’, ‘insoluble’, ‘soluble’ and/or ‘solution’?

- What keywords would they probably not know, eg ‘solute’?

- Some keywords have more than one meaning, eg ‘solution’: when a substance is dissolved in a liquid or a method of solving a problem.

- Think about keywords that are commonly confused, eg ‘dissolve’ is often confused with ‘melting’.

The simple activity above helps the teacher to pre-empt misconceptions that students will have and to be prepared to discuss the dual meanings of certain keywords and how we use those words correctly in science. Another strategy I use is to ask students to raise their hands if they have heard of the word dissolve – resulting in everyone putting their hands up. I then ask students to write down what they think the meaning of the word is. Next, I ask students to raise their hands if they know the correct scientific meaning and, generally, fewer hands go up. The purpose of this hand raising is to ensure that students come to understand that, although they may recognise certain words used in everyday life, these words may have a specific meaning in science or sometimes even a dual meaning. Finally, I give the students the correct meanings.

Discuss the etymology or morphology of the keywords

The keyword we looked at, ‘dissolve’, comes from the Latin dissolvere, meaning ‘to loosen’ and ‘dis-’ is the Latin prefix meaning ‘apart’. I would suggest that you don’t shoehorn links in where they don’t exist.

The Frayer model works brilliantly with more complex keywords. You can ask students to construct concept maps for the keywords to demonstrate the links between the word meanings – this will reinforce spelling, understanding of and the connections between the words.

The Frayer model works brilliantly with more complex keywords (rsc.li/3aOhetu). You can ask students to construct concept maps for the keywords to demonstrate the links between the word meanings – this will reinforce spelling, understanding of and the connections between the words.

Encourage students to talk about the science

In my experience, students often lack confidence when speaking about science. Knowing the meanings of the keywords is not enough. It’s also important that students are able to pronounce the words correctly. A strategy that I regularly use in my lessons with my students aged 11–18 is whole-class chanting of the keywords to practise pronunciation. I admit most are reluctant at first and some a bit embarrassed, but now it is just part of our normal lessons.

Recently, my year 12 class were researching the use of enzymes in industry and at home. When sharing their research with the rest of the class, they could confidently speak about the enzyme-catalysed reactions and substrates, but all the students stumbled over their words when naming the enzymes – the only discernible part of the enzyme names was the suffix ‘-ase’. I then modelled a strategy for them to use with unfamiliar words: students write one of these words on the whiteboard and try to break it down using phonics knowledge or the syllables. They then say each word part and blend them together to make the word, for example with the enzyme ‘polygalacturonase’: poly-ga-lac-tu-ron-ase. Encourage students to say the word out loud and then use it in a sentence with a partner.

The strategies outlined above don’t need much more than a pen and a whiteboard, and take very little time out of lessons. So, what’s the catch? They require teachers to have a good grasp of the language of the topic and the misconceptions associated with the keywords.

No comments yet