Everything you need to know

-

- Salary range: £25–40k

- Minimum qualifications: PhD

- Skills required: analytical skills, technical skills, laboratory techniques, numeracy skills, data analysis, communication skills, report-writing skills, critical thinking, resilience, motivation

- Training required: Training on how to use specialist laboratory equipment

- Work–life balance: Academic research roles might involve working flexible hours and working long hours and at weekends.

- Career progression: There may be the opportunity to progress to a senior role.

- Locations: Find related work experience positions using our map of employers

- Find out more: Explore toxicologist roles in more detail

More profiles like Stephanie's

I think I first decided on a career in science during my PhD but, up until that period, I didn’t really know what a career in science looked like so I did my PhD because I was really enjoying research. At the time, I was really interested in the topic but I didn’t necessarily know what a scientist does until that moment, until that experience.

A career in toxicology interested me because it merged two areas that I’ve always been interested in – one being that of pollution and the impact human activity is having on the world around us and the other being in medicine and sort of medical-type research, so toxicology for me – especially as an environmental toxicologist – merges those two areas together. I’m also interested in how the world around us affects us from a molecular level all the way up to an organism level and toxicology allows you to do that. It’s looking at the world around us which is changing – it’s dynamic, we’re changing it by releasing chemicals or by affecting air quality and the toxicology is letting us ask questions about what that’s doing to human health.

I think a good researcher would be resilient because lots of things can go wrong – things don’t work in the lab, it’s very competitive so you’ve definitely got to have resilience and, with that in mind, you also need to be quite motivated and driven and curious. My area of work – and I think toxicology in general – is quite multidisciplinary. It can integrate physics, chemistry, biology, environmental sciences, different technologies and, I think, as a scientist and as an academic, I’ve got this drive to learn. I like learning new things, I like discovering.

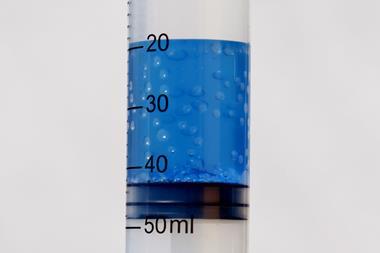

For me, I work on microplastics. They are a mixture – you have the physical plastic particle but you’ve also got plastic chemicals as well and so, in the lab, through toxicology, we’re able to ask very controlled questions about what’s driving the effect. We can look at each in isolation and we can look at the biological mechanisms behind the effect we see as well.

It’s likely that microplastics have been around since mass production began because, while we originally thought that they formed through the degradation of litter in the environment, we now also know that there’s much more immediate processes which generate them like the wear and tear of a carpet, opening a plastic bottle with the lid shedding microplastics, driving synthetic tyres and washing synthetic clothes. These all also generate microplastic. Those processes haven’t changed since the 50s so it’s quite likely that, since the 50s, we have been exposed to it but, in order to make those population-level linkages and links to health, you have to be looking for that specific exposure to begin with and we haven’t, up until now, even considered it because it’s only in the last few years we really realised we were exposed to it so it might be that some of the health outcomes that we are aware of in the western world that have risen over the last 50 years might be connected to plastic usage or exposure to plastic particles or chemicals. It’s just only now that we’re starting to look at the particle exposure to make those links.

First published 2023