Distinguished women chemists were rare in the early 20th century, but their contributions to chemistry are of great significance. Ida Noddack's scientific career centred around her intensive study of the Periodic Table, and resulted in her discovery, with husband Walter Noddack and physicist Otto Berg, of the metal rhenium, and of nuclear fission in the search for element 93.

-

The Noddacks realised element 75 would have properties similar to its horizontal neighbours rather than to manganese

- Ida Noddack's idea of nuclear fission was initially dismissed by eminent scientists at the time

The search for the missing elements, which were predicted by Dmitri Mendeleev in his Periodic Table, was intensive between 1869 and 1891, especially when his prediction proved to be right after the discovery of gallium, scandium, and germanium between 1875 and 1886. These discoveries were made easier because Mendeleev had been able to describe the properties of these elements, which he called eka-boron, eka-aluminum, and eka-silicon, with a fair degree of accuracy.

In 1901 Bohuslav Brauner in Prague predicted the existence of an element between neodymium and samarium, which was confirmed in 1914 by Henry Moseley using x-rays, and became known as element 61. In 1918 Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner in Berlin discovered protactinium and in 1923 Georg von Hevesy and Dirk Coster in Copenhagen discovered hafnium. One year earlier Niels Bohr had confirmed that lutetium is a rare earth and not a member of Group IV of the Periodic Table as was originally thought, thus proposing the search for a missing element in zirconium minerals.

Manganese, the ninth most abundant metal in Nature, was in Group 7 of Mendeleev's Table. Mendeleev had left two gaps below it, which he had marked eka-manganese (Em) and dvi-manganese (Dm) which he predicted would fill the gaps. For both eka-manganese and dvi-manganese, he was unable to predict much of their properties because they were the last two members of the Group. However, he did predict an atomic weight of 100 for Em and 190 for Dm - values that are very near to the actual values of 98 and 182.2, respectively. He also predicted that their compounds would be coloured and there would be a series of oxides corresponding to the oxides of manganese. These gaps remained unfilled for more than 50 years.

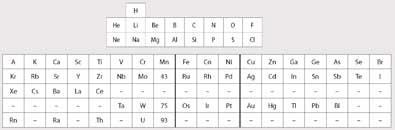

Introducing Ida Tacke

In 1925 Ida Tacke had just taken a position as a chemist in the chemical laboratory at Physikalische Technische Reichsanstalt - a government laboratory in Berlin, headed by Dr Walter Noddack who, in 1926, would become her husband. The two chemists worked together on many problems and published many papers. Figure 1 shows the Periodic Table popular at the time which inspired Tacke. The electronic structure of the transition metals as well as that of the lanthanides had been established a few years earlier by Niels Bohr. The actinides had not been discovered, and eka-thorium was considered to be in Group 4 under titanium, and uranium in Group 6 under chromium.

The existence of the two missing elements - Em and Dm - had been confirmed by Henry Moseley between 1912 and 1914 from x-ray spectra. Moseley also established that the atomic number of molybdenum was 42 and that of ruthenium was 44, confirming that there was a space in Mendeleev's Table for Em, which would be element 43.

Tacke and Noddack set out to find the two missing elements. They made a systematic study of the properties of the elements near these two gaps and found that, though usually there was a gradual change in properties in the vertical groups, there were also sharp changes. From comparisons with other Groups, they concluded that such sharp changes would occur between manganese and the two elements below it. For example, they expected that the sulfides of the missing elements would be insoluble in dilute acid in contrast to manganese disulfide, which is acid-soluble.

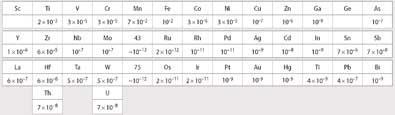

Tacke and Noddack also came to the early conclusion that these elements must have properties different from manganese but be similar to their horizontally-occurring neighbours. They suggested that elements 43 and 75 would have similar relative abundances in the Earth's crust to ruthenium and osmium respectively, analagous to the similarity in the relative abundances of manganese to its neighbour iron (Fig 2). Consequently, they focused their search for the missing elements on ores containing minerals of the metals molybdenum, tungsten, ruthenium, and osmium, the horizontal neighbours of eka- and dvi-manganese.

In June 1925, with the help of Otto Berg, an x-ray specialist at Siemens-Halske in Berlin, Tacke and Noddack identified a new element spectroscopically in a sample of Norwegian columbite

[(Fe, Mn, Mg) (Nb, Ta)2 O6], which they called rhenium in honour of the River Rhine. (Previous researchers had failed to discover the missing elements because they had assumed that these elements would have similar chemical properties to manganese and were searching for them in manganese ores.)

A year later the Noddacks prepared the first gram of the metal from 660 kg of molybdenite ore and later wrote numerous papers on its chemistry. The extraction of rhenium involved repeated separations of molybdenum as the phosphomolybdate and precipitation of rhenium as the sulfide. The relatively pure rhenium sulfide was then reduced to the metal with hydrogen at 1000oC.

Rhenium exists in trace amounts in molybdenite contained in porphyry copper deposits. At present, rhenium is mainly recovered from the dust collected during the roasting of molybdenite concentrate from the porphyry copper ores. The dust contains appreciable amounts of Re2 O7 which is dissolved in water. The solution is purified by ion exchange and then ammonia added to precipitate pure ammonium perrhenate from which metallic rhenium can be obtained by reduction with hydrogen. The content of rhenium in the molybdenite concentrate is usually 500-700 ppm, and the content of molybdenum in the copper concentrate is about 0.05 per cent from which it is separated by flotation. The copper concentrate is normally obtained by flotation of copper sulfide minerals from an ore containing 1-2 per cent Cu.

Noddack and the trans-uranium elements

In 1933 the renowned Italian physicist Enrico Fermi had been working on the bombardment of metals with the recently discovered neutron and studying the products of nuclear reactions. When he and his co-workers bombarded uranium with neutrons, they obtained more than one radioactive product. They suggested that one of these products was formed by neutron capture, and that it was a trans-uranium element or element number 93. Fermi put the new element under rhenium in the Periodic Table and called it eka- rhenium.

His work immediately attracted the attention of Ida Noddack and within the same year, she had published a paper in Angewandte Chemie entitled Element 93 in which she discussed the possibility of discovering the trans-uranium elements, ie elements after uranium in the Periodic Table. In the paper she was critical of Fermi's conclusions, pointing out that all elements in the Periodic System would have to be eliminated in the analysis (radiochemical separation) before one could claim to have found a trans-uranium element. She went further, stating:

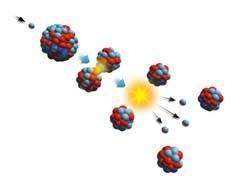

"When heavy nuclei are bombarded by neutrons, it would be reasonable to conceive that they break down into numerous large fragments which are isotopes of known elements but are not neighbours of the bombarded elements".

Thus Ida Noddack had appreciated, before anybody else, the idea of nuclear fission. She had argued that when atoms are bombarded by protons or α-particles, the nuclear reactions that take place involve the emission of an electron, a proton, or a helium nucleus and the mass of the bombarded atom suffers little change. When, however, neutrons, which carry no electric charge are used to bombard atoms, different types of nuclear reaction from those previously known would take place.

Fermi's experiments were immediately repeated by Otto Hahn (1879-1968) and his co-workers in Berlin. They confirmed his conclusions and published a series of papers on extensive radiochemical separations of the so-called trans-uranium elements.

The results, however, became so contradictory that after five years of intensive research and extensive publication the concept of trans-uranium elements had to be abandoned. Hahn then announced in January 1939 the formation of barium during the bombardment of uranium and started speculating about the mechanism of its formation.

At that time Hahn was 55 and director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry (now Max Planck Institute). A well-established scientist, he had travelled abroad on numerous scientific missions, had discovered protactinium with his associate Lise Meitner (1878-1968) in 1918, and had written a textbook on radiochemistry. But, he apparently could not accept Ida Noddack's idea that the uranium atom was split into two fragments. It was Lise Meitner who in 1939 finally explained the results of the work as fission, a few months after she was forced to leave Germany and move to Stockholm.

In October 1969 Ida Noddack was invited by the former USSR Academy of Sciences to the Mendeleev's Periodic Table centennial celebrations in Leningrad (now St Petersburg). She was then the only living chemist who had discovered a naturally occurring element. (Among those who attended was Emilio Segrè (1905-89), who discovered the synthetic element technetium.) Although Noddack was unable to attend because of sickness, her paper The periodic system and the search for the eka-manganeses was translated into Russian and read at the conference. In this paper she told of the circumstances of her discovery and had the last word regarding the controversy on the trans-uranium elements which she believed tainted her scientific career.

Fathi Habashi is professor emeritus of extractive metallurgy in the department of mining, metallurgical, and materials engineering at Laval University, Quebec City, Canada G1V OA6.

Further Reading

- F. Habashi, Ida Noddack (1896-1978): personal recollections on the occasion of the 80th anniversary of the discovery of rhenium. Québec: Métallurgie Extractive, 2005.

- M. E. Weeks, Discovery of the elements. Easton, Pennsylvania: Journal of Chemical Education, 1960.

- B. Bryskin (ed), Rhenium '97. Warrendale, PA: AIME-The Mineral, Metals, and Materials Society, 1997.

Ida Noddack - a brief history

Ida Eva Tacke was born on 25 February, 1896 in Lackhausen, a small village near Wesel on the Rhein in Germany north of Köln. She studied chemistry in Berlin at the Technische Hochschule (now Technische Universität) in Charlottenburg, obtaining the Diplom-Ingenieur degree in 1919, for which she won the first prize for chemistry and metallurgy, and the Doktor Ingenieur in 1921. From 1921 to 1923 she worked as a chemist at Allgemein Elektrizität Gesellschaft, and from 1924 to 1925 at Siemens-Halske, both in Berlin. In 1925 she joined the Physikalische Technische Reichsanstalt, a government laboratory in Berlin. In 1926 she married Dr Walter Noddack (born 1893), head of the chemical laboratory where she worked.

In 1935, the couple moved to Freiburg in Baden, where Walter Noddack was appointed professor of physical chemistry at the University of Freiburg and Ida Noddack a research associate. In 1942 the Noddacks moved to Strassburg University where they remained until 1944, when the city was liberated by the French. Between 1944 and 1956, she was apparently out of work. During this period, the Noddacks spent some time in Turkey.

In 1956 they moved to the newly founded Staatliche Forschungs Institut für Geochemie (State Research Institute for Geochemistry) in Bamberg, Germany. Walter Noddack died in 1960 and Ida Noddack retired in 1968.

She spent her last years in Wohnstift Augustinum, an apartment building for elderly people in Bad Neuenahr on the Rhein near Bonn.

She died on 24 September, 1978. The Noddacks had no children.

Awards and honours

In 1925 Ida Tacke was the first woman to give a major address to the Society of German Chemists. She was honoured with several awards throughout her scientific career. She received the Liebig Medal of the German Chemical Society in 1931, the Scheele Medal of the Swedish Chemical Society in 1934, and the High Service Cross of the German Federal Republic in 1966. She was awarded honorary memberships in the Spanish Society of Physics and Chemistry (1934), and in the International Society of Nutrition Research (1963), as well as an honorary Doctorate of Science by the University of Hamburg (1966). Her name was given to a street in her home town of Lackhausen.

No comments yet