Martyn Poliakoff and Brady Haran pay tribute to Ron Nyholm

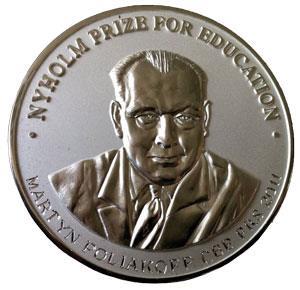

This is the story of an unusual partnership which recently led to our filming a video tribute to Ron Nyholm, the founder of Education in Chemistry. We have very different backgrounds: Brady is a video journalist with a passion for science and Martyn is an inorganic chemist turned green chemist. The trigger for our interest in Nyholm was the award of the RSC Nyholm Prize for Education to Martyn in recognition of his role in promoting chemistry on YouTube. This has been done via the website Periodic Table of Videos, created and filmed by Brady. The Prize included an invitation to give a lecture to the RSC Education Division. Since Martyn has had minimal formal training in the area, the prospect of speaking about education was daunting, hence the idea of a tribute to Nyholm.

Initial experiments

Science is widely shown on television but, in the UK at least, the results are often predictable and formulaic. The outcome is obvious from the outset; one knows that the scientist must have made a big discovery or the programme would not have been shown. Much of the tension of research is lost; will the experiment actually work?

In 2007, Brady began doing things differently. He started filming scientists and engineers carrying out their normal work at the University of Nottingham. The resulting videos were uploaded to a YouTube site, Test Tube, showing the trials and tribulations of real scientific life: grant proposals succeeding or being rejected, apparatus being switched on for the first time, etc.

Elements ignored

In May 2008, Brady filmed Martyn for Test Tube and there was an immediate rapport. A few days later, something triggered Brady's schoolboy memory of staring at the periodic table hanging in his classroom and wondering why his teacher ignored most of the elements. So why not make a video about each of the 118 elements? Martyn was sceptical. How could one make a video about an element such as 117, for which not even a single atom had ever been observed? However, he was persuaded to try, funding was found, and Martyn was joined by three colleagues, Pete Licence, Debbie Kays and Steve Liddle. The whole project (118 videos plus an introduction and trailer) was completed within five weeks. By then, the website already had a substantial following on YouTube and attracted widespread publicity.

Power of YouTube

In fact, the viewers were demanding more and so the project has continued to this day with new videos being uploaded every week. The topics have been broadened to include molecules and chemical news (eg the Red Sludge in Hungary) and road trips (including to Ytterby, Brazil and Australia). By mid-November 2012, there were 453 videos, with more than 28.4 million views and over 135 000 YouTube subscribers across the world. Periodic Videos has spawned several more YouTube channels, all made by Brady, which cover a wide range of subjects.

The chemistry videos are undoubtedly successful and several articles have discussed their impact.1,2. A key question is 'why?' The approach is quite different from conventional educational videos. There are no learning objectives and no scripts or storyboards. Different contributors to a video are unaware of what the others have said. The videos are edited ruthlessly by Brady; needlessly technical details may be cut, while failed experiments are often included. The first time the chemists see the videos are after they have been uploaded to YouTube. Such a level of trust between scientist and journalist is perhaps unusual but, in Brady's case, it works really well. The results speak for themselves, with viewer comments such as: 'I'm a first year Geography student, but the videos . really sparked my interest in chemistry, something that I didn't think was at all possible . I just wanted to say thank you, and that I appreciate the work that you do.'

Nyholm's legacy

... Alice understood why her grandfather is still honoured 41 years after his death. What more could one want?

This brings us back to Ron Nyholm. With Martyn's award recognising the use of video communication, it seemed most appropriate that his lecture be accompanied by a film. Many people are aware of Nyholm's work with Ron Gillespie in developing the Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VESPR) approach to molecular structure. What struck us was that most of the topics currently considered as defining inorganic chemistry, were first highlighted by him. His obituary stressed his powerful personality, lighting up any occasion by his presence. We wanted to convey all of this to show how his scientific legacy lives on.

We knew nothing about Nyholm's family. But such is the power of the internet that, a month after the video was uploaded, we received an email from Peter Nyholm in the US. 'Dear Martyn, From time to time I look up my Dad on the internet - for old time's sake I guess - and I have to tell you I just loved your YouTube video about your award and about my Dad. He would have loved it too.'

The result was that Nyholm's daughter and her family came to hear the lecture in Edinburgh and, for the first time, Nyholm's granddaughter Alice understood why her grandfather is still honoured 41 years after his death. What more could one want?

Martyn Poliakoff is a research professor at the University of Nottingham Brady Haran is a video journalist.

References

1. B Haran and M Poliakoff, Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 180 (DOI: 10.1038/nchem.990)

2. B Haran and M Poliakoff, Science, 2011, 332, 1046 (DOI: 10.1126/science.1196980)

No comments yet