This year marks the 350th year of the Royal Society. Sir John Rowlinson, University of Oxford, takes us on a brief historical excursion through one of the nation's champions of scientific endeavour

The minutes of the meeting that we celebrate this year as the foundation of the Royal Society read:

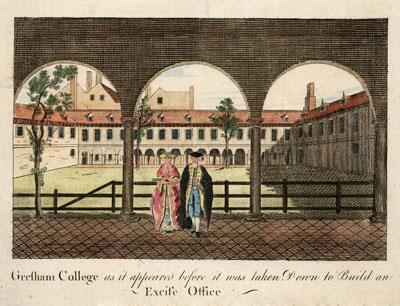

On the 28 November, 1660, a group of eleven men gathered in Gresham College [London] to hear Christopher Wren lecture on mathematics, and afterwards, withdrew for mutuall converse. Where among other matters that were discoursed of, some thing was offered about the designe of founding a Colledge for the promoting of Physico-Mathematical Experimental Learning.

The time was auspicious - throughout Europe experiment was ousting philosophy and theology as a source of knowledge of how the world worked, and the civil war through which Britain had just come through had made men welcome the chance to discuss 'natural philosophy' in an atmosphere free from political and religious arguments. The Society's motto, Nullius in verba, would emphasise its reliance on experiment rather than on metaphysical arguments.

Early success

In 1662 the new Society gained royal recognition, as expressed in its Charter, but was a self-governing body, independent of the State for its conduct and expenditure. Under the direction its German-born secretary, Henry Oldenburg, the Society established extensive relations with scientists abroad and, in 1665, launched Philosophical Transactions, the first journal that is still in existence devoted to the publication of scientific papers. In 1687, the most important scientific book of the 17th century - Isaac Newton's Principia mathematica - was published under the imprint of the Society's then president, Samuel Pepys.

After this successful start the Society passed through its least productive period in the 18th and early 19th century, though it supported explorations such as the voyages of James Cook, who was elected a fellow in 1776. The 'fellowship' became dominated by gentlemen of rank and wealth, and its primary purpose of promoting 'science' became increasingly taken over by specialist societies early in the 19th century. The astronomers and botanists led the way and were followed by many others, including the chemists in 1841. Indeed, it was dissatisfaction with the composition and performance of the Society that led to the formation of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1831, which took the lead in promoting science throughout the rest of the century.

From the middle of the 19th century the Society began a process of reform, restricting its fellowship to those with significant scientific achievements from the UK and from what is now called the Commonwealth. Gradually the tide turned and the Society once again became the dominant organisation in promoting science in the UK. Fellows freely gave advice on scientific matters, asked or not, to the government of the day. In 1849 the Society accepted a Government grant of £1000 a year to be distributed to those, whether fellows or not, who could make a case for help with the expenses of their research.

Moving forward

In the 20th century the Society acquired all the activities and duties that naturally fall to a national academy of science, but now on a scale that makes earlier efforts seem marginal to the national scientific effort. It retains, and guards fiercely, its independent status, receiving from the State the free occupation of its premises at Carlton House Terrace, but no subsidy for its core activities.

The annual parliamentary grant is now about £26 m and supports, in whole or in part, 12 research professors, about 350 research fellows, and about 2000 research and conference grants each year. The research fellowships, which can be held for up to 10 years, have probably done more to maintain the standard of research in British universities over the past 40 years than any other official or unofficial action. The burden of running this grant-giving effort falls directly on the permanent staff of the Society, but the decisions of the merits of each application are made by the fellows who give freely of their time and judgment in directing the work.

The Society's primary role of promoting science is now increasingly concentrated in interdisciplinary fields, such as climate change, space research and the control of nuclear materials, which do not naturally fall to any one of the specialist scientific societies. The Society's library, archives and collection of portraits are now an important contribution to the work of historians of science from home and abroad.

The Royal Society is a body steeped in tradition but it tries hard not to stagnate and is always looking for new and increasingly ambitious ways of securing the future of British science. Its recent publication, The scientific century: securing our future prosperity, published in March, is testimony to this continuing remit.

No comments yet