Cambridge chemists find out how secondary school chemistry students compile word equations.

Keith Taber and Pat Bricheno of Cambridge University have completed a study of students' understanding of chemical word equations.1 For the study 300 secondary students had to complete five word equations where one item was omitted from each equation. They were asked to name the missing substance and explain their answers.

Based on the results of the study, about 65 per cent of the answers provided were judged correct and 20 per cent incorrect. The other 15 per cent of responses were technically wrong but were considered to be close to the right answer. This shows that most respondents were able to offer a correct or nearly correct answer. However, if the non-responses are assumed to indicate that the student could not offer any answer, then about a quarter of possible responses were incorrect.

Analysis of the explanatory statements from the students showed that in the main they used, either separately or in combination, seven different strategies to complete the equations. The first strategy, used by only a few students, was simply to recall the reaction from their lessons. Since there are many reactions for students to learn the potential for making an error is high.

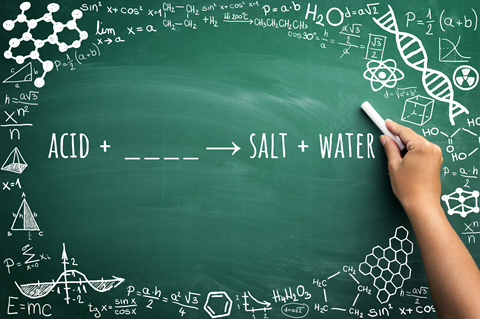

The approach that was largely associated with correct responses involved using a standard schema, such as acid + base → salt + water. The research showed that students who identified the correct reaction type often completed the task with ease.

A similar but less successful strategy was where the student applied patterns based on reaction types, eg metals react with acids to give hydrogen. However, this was unsuccessful when the student held only a partial knowledge of the reaction type.

A fourth strategy led students to base their response on their flawed understanding of the reactivity of a substance. For example, in a reaction involving potassium hydroxide such students would base their answer on the reactivity of potassium.

The fifth strategy used the principle of the conservation of matter and while this could lead to correct answers some students misapplied their chemical knowledge. The final two approaches relied either on the 'story' of the equation looking right or simply making a guess as to what looked to be the most appropriate answer.

Whatever process was used, the students succeeded only when they brought together several facets of chemical knowledge.

References

- K. S. Taber and P. Bricheno, Int. J. Sci. Educ., 2009, 31 (15), 2021.

No comments yet