Antimony, symbol Sb, one of the earliest elements to be recognised, demonstrates that there is much intriguing chemistry to be found in the nether regions of the Periodic Table. A metalloid with a strong affinity for sulfur, antimony is pharmacologically active and has been used in medicines, but is also a poison.

-

Antimony - used in ancient times as an emetic and in cosmetics

- Antimony lives in the neighbourhood of arsenic and shares similar traits

Evidence for the occurrence of antimony can be traced back to antiquity.1 The name comes from the Greek, anti and monos, meaning 'metal not found alone'.2 Indeed, antimony is usually found as the sulfide ore, stibnite, Sb2S3, the black form of which was used by ancient Egyptian women as a cosmetic for darkening their eyebrows and eyelashes.3,4

The earliest record of metallic antimony is thought to have been provided by the 1st century Greek physician Dioscorides in his five-volume treatise De materia medica, one of the most influential works on pharmacology for 16 centuries. Dioscorides' treatise refers to the metal's potential medical uses, for example in the treatment of skin disorders.

The art of preparing pure metallic antimony is described in the 17th century work Triumphal chariot of antimony by Basil Valentine which, though published in 1604, is thought to have been written about 250 years earlier.4 The process involved roasting stibnite to form the oxide, followed by reduction with carbon to obtain the free element. In 1615 German chemist and physician, Andreas Libavius described an alternative method, in which stibnite was reduced directly to metallic antimony by reaction with iron.

Other references to antimony followed, notably Nicholas Lémery's Treatise on antimony, published in 1707.

A little bit of chemistry

Antimony occurs in Group 15 of the Periodic Table,3 and is generally considered to be a metalloid rather than a metal, because it does not always behave in the way that is characteristic of metals. For example, it is a relatively poor conductor of electricity, with a resistivity of 41.7µ cm compared with 1-2 μ Ωcm for metals such as copper.3 Antimony is also a relatively poor conductor of heat. The element is similar to arsenic, which lies immediately above it in the Periodic Table, in that it resembles a metal though antimony is less reactive, and is stable in air and moisture, unlike arsenic, which tarnishes in damp air.3

Approximately 116,000 tonnes of antimony are produced worldwide each year,3 mainly in China. The main use of the element is in a variety of alloys. Antimony alloyed with lead, for example, is used to make storage cases for batteries, and also in solder and type metal. Alloyed with these metals, antimony increases the hardness and stiffness of the combined metals and also improves their corrosion resistance. Antimony also forms III-V semi-conductors such as AlSb, GaSb and InSb, which are used in infrared devices and diodes. Small percentages of antimony oxide are used to remove bubbles in optical glass and to oxidise and thus decolorise speciality glasses pigmented green by traces of iron, and as an opacifier in porcelain enamel and ceramic glazes. Antimony sulfide is used in the vulcanisation of rubber, and as a pigment to vary the colour from vermillion to yellow, depending on the extent to which it has been allowed to oxidise. Antimony sulfide also finds relatively minor uses in fireworks, ammunition primers and tracer bullets.

Two allotropic forms of elemental antimony exist, ie the stable, metallic form, and the meta-stable amorphous grey form.3 There was also thought to be a third allotrope, the explosive antimony, first obtained by British chemist George Gore in 1858. Gore was doing an electrolysis on SbCl3, and rather than preparing free antimony, as he assumed he would, he obtained a mixture of elemental antimony with between 4 and 20 per cent SbCl3 deposited within it. This solid solution has a shiny appearance and looks like polished graphite, but when scratched, undergoes a violent exothermic reaction that converts the grey allotrope of antimony to the metallic form.

In compounds, antimony exhibits oxidation states of +V and +III, the latter being the more stable. (Note, however, the pentavalent fluoride has particularly striking properties, with the ability to form strong protionic acids (up to 1012 times stronger than H2SO4.) The element has strong affinity for sulfur as evident in its occurrence as the sulfide, and also in the mechanism of its toxicity, ie via interaction with sulfur-containing proteins. And this leads us into another important aspect of antimony - its pharmacological role.

A poisonous twist

In times gone by antimony has been used both as a medicine and as a poison. Popular in Roman times and later in the 15th and 18th centuries were 'antimony cups'.5 Wine was allowed to mature in cups made of cast antimony metal and later the alloyed metal. The resulting drink contained reasonable amounts of antimony, which was considered a 'universal medicine' for treating 'all ills' though in reality, many deaths resulted from consuming this mixture.

Another important medicinal compound, first described in the early 1600s by the German alchemist, Hadrian Mynsicht,4 was 'tartar emetic', ie potassium antimony tartrate, KSbO.C4H4O6. This salt became used in conventional medicines as an emetic6 - a substance that induces vomiting - which was perceived to be a useful treatment because it helped the body rid itself of damaging substances, such as adulterated or decaying foodstuffs. Tartar emetic is still used in homeopathic medicine, albeit at extremely low doses.

When taken in excess, potassium antimony tartrate causes severe vomiting and purging, and also depression of the nervous system. These symptoms are similar to those of arsenic poisoning, but with antimony their onset is sooner, and victims are aware of a metallic taste in their mouth.6 Death occurs as a result of exhaustion, following loss of appetite and emaciation. Victims of antimony poisoning suffer gastric intestinal irritation, and internal investigation post-mortem reveals orange stains along the walls of the alimentary canal. These are caused by the formation of Sb2S3 from hydrogen sulfide generated as a result of putrefaction. The mode of action of potassium antimony tartrate is reasonably well understood. Animal studies have shown that the compound accumulates in the red blood cells and is transported to the kidneys, where it reduces the effectiveness of the enzyme phosphofructokinase. This inhibits the ability of the cells to utilise glucose, the oxidation of which is the body's primary source of energy.8 This probably accounts for the exhaustion experienced by the victims.

Antimony is taken up by the red blood cells by interaction with the -SH groups in glutathione, a tripeptide found in the red blood cells.9 The Sb(III)-glutathione complex readily exchanges antimony-III ions with the surroundings, and the formation and dissociation of this complex is responsible for the efficient transport of antimony to the tissues of the body in vivo. The affinity of antimony for sulfur is thus critical to its toxicity.

Potassium antimony tartrate has been used by murderers, partly on account of its wide availability, but also because the symptoms of its use are difficult to tell from those of certain organic diseases, such as cholera.6 A particularly famous case involving this substance was that of George Chapman (See Box).

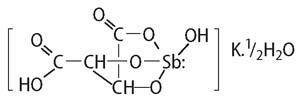

As a final point, though potassium antimony tartrate had been known for about 400 years, it had to wait until 1965 for its structure to be elucidated. In that year, Grdenic and Kamenar at the University of Zagreb, using X-ray diffraction, discovered the structure:7

Their results further revealed that the salt was a derivative of the antimonite ion [Sb(OH)4]- with the antimony atom in a deformed trigonal bipyramidal geometry - but that, as they say, is another story.

John Nicholson is professor of biomaterials in the department of chemical and pharmaceutical sciences at the University of Greenwich, Medway Campus, Chathham, Kent ME4 4TB.

A barber's poisonous trail9

George Chapman was of Polish origin, his real name being Severin Klosowski. He was born in 1865, and as a young man worked as an assistant surgeon. In 1887, he immigrated to England and settled in London, where he worked as a barber and had a series of relationships with women. One of these was Annie Chapman, whose surname he took. He later lived with a Mrs Mary Spink, whom he poisoned with tartar emetic on Christmas Day 1897.

In rapid succession he had similar relationships with Bessie Taylor (who died in February 1901) and Maud Marsh (who died in October 1902). In the case of the latter, the doctor refused to issue a death certificate, though it is not clear why, and at the subsequent post-mortem 7.24 grains (ca 470 mg) of antimony were found in her stomach. Chapman was arrested, and tried for all three murders in March 1903. He was convicted only of Maud's death, a decision that took the jury just 11 minutes to reach. He was hanged in Wandsworth jail soon afterwards.

References

- G. T. Seaborg and W. D. Loveland in The new chemistry, Nina Hall (ed), chap 1. Cambridge: CUP, 2000.

- C. R. Hammond in Handbook of chemistry and physics, D. R Lide (ed), section 48, 2nd edn. Florida: CRC, 2001-02.

- N. N. Greenwood and A. Earnshaw, The chemistry of the elements, 2nd edn. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1997.

- J. R. Partington, A short history of chemistry. London: Macmillan, 1948.

- T. A. O'Donnell, Superacids and acidic melts as inorganic reaction media. New York: VCH, 1992.

- K. Watson, Poisoned lives. London: Hambledon and London, 2004.

- D. Grdenic and B. Kamenar, Acta Cryst., 1965, 19, 197.

- R. Poon and I. Chu, J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol., 1998, 12, 227.

H. Sun, S. C. Yan and W. S. Cheng, Eur. J. Biochem., 2000, 267, 5450.

No comments yet