Researchers use a particle accelerator to bring information on enigmatic element 102 to the table

-

Download this

Use this story and the accompanying summary slide for a real-world context when studying elements and the periodic table with your 14–16 learners.

Download the story as MS Word or PDF and the summary slide as MS PowerPoint or PDF.

Nobelium is now the heaviest element to have been directly detected in a larger molecule. These nobelium complexes were created as part of a series of investigations charting the chemistry on the edge of the actinide series.

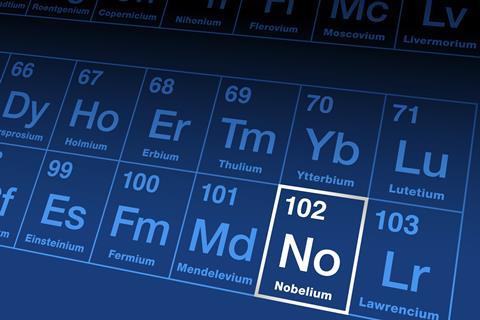

Nobelium is element 102 and it is too unstable to exist naturally on Earth. Scientists first made nobelium in particle accelerators in the 1950s, with Swedish, US and Russian teams all claiming to be the first to create it. Due to the challenges with making it, nobelium has remained one of the most mysterious elements on the periodic table, with no known uses and very few of its chemical properties confirmed experimentally.

A complex situation

Scientists at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, US, first created nobelium ions by firing a calcium beam into a lead target using a cyclotron particle accelerator, resulting in nuclear fusion. The team found that the nobelium ions then rapidly reacted with trace amounts of nitrogen and water present in the accelerator to produce a variety of nobelium complexes. These findings mean that nobelium is now the heaviest element with definitively identified compounds.

The scientists now plan to investigate the next elements in the actinide sequence, including lawrencium (element 103), rutherfordium (element 104) and dubnium (element 105).

Thomas Albrecht, an actinide chemist at the Colorado School of Mines, US, who was not involved in this work describes these findings as an ‘important milestone in expanding our understanding of how chemistry evolves in the outer reaches of the periodic table’.

This article is adapted from Kit Chapman’s in Chemistry World.

Nina Notman

Reference

J L Pore et al, Nature, 2025, doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09342-y

Download this

Summary slide with questions and the article for context when teaching 14–16 lessons on elements and the periodic table: rsc.li/4izxHVZ

Downloads

Nobelium revealed as the heaviest element with identified compounds student sheet

Handout | PDF, Size 0.17 mbNobelium revealed as the heaviest element with identified compounds summary slide

Handout | PDF, Size 0.26 mbNobelium revealed as the heaviest element with identified compounds student sheet

Editable handout | Word, Size 0.53 mbNobelium revealed as the heaviest element with identified compounds summary slide

Editable handout | PowerPoint, Size 0.51 mb

No comments yet