Ruth Jarman opens the eyes of trainee teachers to opportunities to help students learn chemistry in informal settings

Each year the number of informal sources and settings where children and adults can learn about science and technology outside of the classroom is increasing, as – generally – is their quality. Newspapers, news websites, popular science books, and television and radio programmes are the main sources, while public settings now range from shopping centres, to sports arenas, music festivals, science centres and museums.

Chemistry tends to be less well represented in these informal outlets than the other sciences. In the news, for example, there are fewer reports explicitly linked to chemistry than those related to biology or physics.1 To a certain extent this is because news stories that could have been framed as the fruits of chemistry research are often presented as flowing from biomedical research instead. There are also fewer popular science books dealing explicitly with chemistry compared with those with biology or physics themes. In part, this reflects publishers’ perception of their audiences’ interests. Pulitzer prize-winning science writer Deborah Blum’s publishers, for example, advised her that ‘the word chemistry on the book’s cover would tank sales’.2

Chemistry features less frequently in television documentaries, shows and films than biology and physics.3 Where it does, the focus is as often on the negative as on the positive. Breaking bad may have presented chemistry as cool, but it also presented chemistry as criminal.

Finally, chemistry often loses out to physics and biology in science centres and science museums. This is because the subject can be challenging to present in an engaging fashion in these settings. Most science centres and science museums do however run chemistry demonstration shows and workshops, and some also offer chemistry-related displays. A notable example is the Elements exhibition, which is currently running in the National Museums Northern Ireland’s Ulster Museum in Belfast.

Encouraging engagement

Formal science education has an important, but too often unrecognised, role in making young people aware of – and giving them the skills needed to engage with – contexts for science learning beyond the classroom. This applies to chemistry as much as it does to other scientific disciplines. Though they may be less conspicuous, there are sources and settings for informal learning in chemistry and our pupils should be alerted to their significance.

At least three benefits can flow from incorporating such contexts, even in a small way, into chemistry curricula.

Firstly, identifying and discussing chemistry in the news, encouraging engagement with online chemistry resources, promoting the reading of popular chemistry books, arranging educational visits with a chemistry focus all have the potential to enrich and extend our pupils’ experience of the subject, while stimulating interest and involvement. After all, by their very nature, these sources and settings are designed to catch attention and often also to fuel curiosity and a sense of wonder. Science centres and museums, for example, aim to engage at an emotional as well as an intellectual level.

However, there is a second reason for including a consideration of informal chemistry resources in our chemistry courses. If young people are alerted to a range of ways in which they can explore chemistry beyond the classroom, and helped to feel comfortable accessing them, then this may lay a foundation for lifelong learning. The importance of this is well illustrated by the very telling findings of the recent Royal Society of Chemistry’s research into public attitudes to chemistry.4

This study revealed that public perceptions of chemistry were more positive than had been anticipated. Rather than being antagonistic, people tended to be simply neutral toward the subject. However, many struggled to see chemistry as relevant in their daily lives and they lacked much emotional connection with it. Generally, individuals did not feel informed about chemistry or particularly confident about accessing it. Significantly, they reported limited encounters with chemistry in the media, though there was evidence they may have been coming across chemistry-related news reports but failing to recognise them as such.

Making young people aware, while they are still at school, of the channels through which they can continue to find out about chemistry beyond formal education and giving them opportunities to actively engage with these channels may be one way we can begin to address these issues.

There is a third possible benefit of creating bridges between formal and informal contexts for learning. Teachers who acknowledge the importance of informal learning in chemistry may also be able to take better account of pupils’ own out-of-school science-related experiences. These experiences are sometimes brushed aside in the classroom, rather like a restaurant with a big sign saying ‘only food purchased on these premises may be consumed here’.

Teaching the teacher

If activities aimed at encouraging and equipping pupils to engage with informal chemistry learning sources and settings are to be included in our science courses, then a case can be made for exploring relevant approaches in teacher professional development programmes, including in initial teacher education.

The opening of the Elements exhibition at the Ulster Museum provided a superb stimulus and opportunity for this to be done within the science PGCE (postgraduate certificate of education) programme offered at the nearby Queen’s University Belfast’s school of education.

With funding from the Royal Society of Chemistry Northern Ireland section, a chemistry in the museum day was planned for the 2013/14 PGCE programme. The event aimed to:

- Enhance the PGCE students’ awareness of sources and settings for chemistry learning beyond the classroom and prompt them to introduce their pupils to opportunities for learning chemistry informally.

- Extend the chemistry knowledge of those PGCE science students whose specialism is biology and physics.

- Develop students’ abilities to prepare high-quality resources for encouraging and supporting beyond the classroom learning in chemistry.

- Encourage the students, as newly-qualified teachers, to act as ambassadors in schools for the Elements exhibition and to demonstrate how it can help support the chemistry curriculum.

The event involved university staff, museum staff, the RSC regional coordinator and the science communicator Paul McCrory.

A day in the museum

A talk entitled What’s wrong with chemistry? started the day. The entry point was a discussion of the paradox that, while chemistry makes an immense contribution to almost every aspect of modern living, a number of research studies have reported that many young people and adults fail to recognise its relevance to their daily lives.4,5 The trainee teachers explored ways to point out links with everyday life, focusing on four approaches, each with connections to informal learning sources and settings.

- Setting up classroom chemistry exhibitions, with examples of how this might be done.

- Sharing chemistry anecdotes, with reference to popular science books as a source of such stories.

- Starting from everyday contexts, with reference to how a news story about the making of medicines could add relevance to a traditional chemistry practical – the preparation of magnesium sulfate.

- Actively encouraging pupils to engage with a wide range of sources and settings for informal chemistry learning and providing regular opportunities and prompts for them to do so.

Next up was an illustrated talk from Paul on the wide variety of informal sources and settings that offer opportunities for chemistry learning. Reference to science centres and museums set the scene for our visit to the Elements exhibition itself. This was introduced by its curator and the PGCE students were then challenged to identify as many links as possible with Key Stages 3 and 4 and post-16 chemistry curricula. A plenary provided opportunities for sharing their ideas and insights.

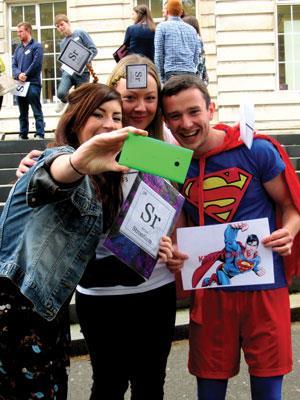

Before lunch the students participated in a periodic table photo shoot on the steps of the museum. In advance of the event, each had been assigned an element and invited to prepare an A4 page featuring its symbol. After a few minutes of utter chaos, a human periodic table began to emerge.

In the afternoon, workshops were presented that explored the importance and design of pre-visit and post-visit activities for pupils. In small groups, the PGCE students were tasked with devising an idea for a pre-visit and/or post-visit activity, which they then had to present to their peers. There was strong emphasis on encouraging them to think as creatively as possible and on celebrating the informal characteristics of the museum experience.

It was suggested that preparatory and follow-up lessons, and indeed the visit itself, should be distinctly different from a routine chemistry class. The possibilities, for example, for including elements of free-choice and of accenting affective aspects of the visit were explored.

Despite the limited time available, participants came up with some interesting and inventive ideas. One group proposed an elemental Dragons’ den, where, working in teams, pupils would select an element from the exhibition that they considered a ‘super element’ and, post-visit, would pitch their choice to their peers. Other ideas included pupils codebreaking with chemical symbols, preparing profiles for an elementary dating agency, designing a card-match game for visitors to the exhibition, designing an elements catchphrase competition (‘say what you C’) and adopting an element and explaining why it had been awarded a place in the exhibition.

After the event

Following on from the chemistry in the museum day, the PGCE students were asked to report the key messages they had taken away from the event. Typically, their responses showed they had found it interesting and instructive. The chief lessons learned related to how to organise and manage an educational visit and the importance of preparatory and follow-up activities. It was particularly pleasing to note how many students referred to the wide range of science-related links in the museum, from ways of stressing the relevance of chemistry, to chemistry demonstrations and how to present them, and to creative approaches to planning learning experiences and resources.

The commitment displayed by the students during their museum visit and the learning outcomes they reported were exactly what the organisers were hoping for. Prompted by this response, the event is now an annual feature of the PGCE programme. The 2014/15 students engaged with equal enthusiasm in the activities of the day. Their element ‘dress-ups’ were even more exuberant and their ideas for pupil pre- and post-visit lesson plans were just as creative. We had Cl17U92Es99O8, where questions were placed in ‘rooms’ representing the four aspects of the exhibition: earth, life, fashion and death. As for the murder, the first letters of the answers, rearranged, spelled out ‘Who dunnit’. Other ideas were adopt an element, bingo, blind date, news reports and chembook (as opposed to Facebook). One group suggested the class, as a follow-up activity, prepared promotional videos aimed at encouraging teachers to bring their pupils to visit the Elements exhibition.

It is to be hoped that, as they enter the teaching profession, this experience will encourage the PGCE students to actively raise their pupils’ awareness of informal contexts for chemistry learning and to build the young people’s confidence to access them. After all, as one student concluded: ‘I have discovered that informal learning [in chemistry] can be a very valuable and enriching experience for everyone and that there are many more facilities for it than I ever thought.’ and another ‘I really enjoyed the day at the museum and I was really inspired by the Elements exhibition’.

Ruth Jarman is a lecturer at Queen’s University Belfast’s school of education

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the invaluable contribution of those who funded and presented at the chemistry in the museum day: the RSC Northern Ireland section, Paul McCrory at Learn Differently, Mike Simms and Geraldine Macartney at National Museums Northern Ireland and Angela McKeown then RSC regional coordinator.

References

1 R Jarman and B McClune, Developing scientific literacy: using news media in the classroom, p 23, Open University Press, 2007

2 Recounted in M R Hartings and D Fahy, Nat. Chem., 2011, 3, 674 (DOI: 10.1038/nchem.1094)

3 National Research Council, Chemistry in primetime and online, The National Academies Press, 2011

4 Royal Society of Chemistry, Public attitudes to chemistry, 2015

5 For example see P Lord, J L Harland and C Gulliver, An evaluation of the Royal Society of Chemistry careers advice and materials, Royal Society of Chemistry, 2006 (pdf)

No comments yet