In the early Middle Ages 'physicians' treated most illnesses ineffectually, with herbs and plant extracts. Paracelsus (1493-1541) challenged this practice, suggesting inorganic chemical remedies would be better. Consequently, chemists began to explore the newly discovered elements and their salts for curative properties.

-

Hennig Brandt discovered phosphorus in 1669

-

The element was used to treat a variety of illnesses from gout to tuberculosis

Elemental yellow phosphorus was isolated by the Hamburg merchant Hennig Brandt (or Brand) in 1669. He allowed urine to ferment, boiled it down and dry-distilled the residue with potassium hydrogensulfate. The product, the more reactive of the two common allotropes of phosphorus, spontaneously inflamed in air (at ca 37°C) and glowed in the dark. With such seemingly 'miraculous' properties some experimentalists speculated that the new element might have a beneficial medical effect, if applied in the right doses to the right diseases. The search was on for a medicinal use for phosphorus and this continued up to the start of the 20th century.

Hennig Brandt - a brief biography

Brandt served as a junior army officer in the Thirty Years War before he was able, with the assistance of his first wife's substantial dowry, to pursue his interests in alchemy. In part, he wanted to find the philosopher's stone, which would 'turn base metals (such as lead) into gold'. By the time his wife died, her fortune was exhausted, but his second wife was a wealthy widow, allowing him to continue his search. He investigated urine and, though this led him to discover phosphorus (boiling 50 buckets of urine to obtain 120 g of the element), it proved unsuccessful in transforming lead to gold. Desperate for funds, he sold his secret to Daniel Kraft of Dresden, another alchemist, on the condition he did not tell the German alchemist Johann Kunckel, who was later to prepare phosphorus from urine himself and publish his findings. Kraft turned his information into gold, demonstrating the properties of phosphorus to the courts of Europe, while for over a century, Kunckel was credited with its first discovery.

Kunckel's pills

Phosphorus was first used medically around 1710. Johann Lincke, a German apothecary, sold pills, allegedly containing 200 mg of yellow phosphorus protected from the atmosphere by a surface layer of gold or silver, for treating 'colic, asthmatic fevers, tetanus, apoplexy and gout.'1 (Elemental phosphorus is a powerful reducing agent and the pills become coated with silver simply by dipping them in a solution of AgNO3.) However, a fatal dose of phosphorus can be as low as 1 mg kg-1 body mass, which suggests that Lincke, and other early practitioners were, fortunately, using impure forms of the element. He called them 'Kunckel's pills' after Johann Kunckel (1630-1702), a German chemist who continued Brandt's work on the element, and cast it into spherical pills (stored under water) to use in later chemical experimentation.

The first detailed accounts of the medicinal use of phosphorus were published in 1751 in Haller's Collection of (medical) theses. A Dr Gabi Mentz reported that phosphorus was a 'cure' for:

- a 'malignant petechial [spotty] fever' which led to 'obstinate diarrhoea with intense anxiety of the praecordia [chest], delirium and general prostration of the powers'.2 The patient recovered after receiving several doses of 2 grains (=130 mg) of phosphorus dispersed in an opium substrate;

- 'bilious fever'; and

- common typhus:

on the third day of the disease [typhus] the patient was deprived of the use of his external senses; that he became delirious and exceedingly exhausted. Two grains of phosphorus was given to him at 2 o'clock, and two more in the evening, which restored him to his senses, and occasioned a copious sweat. Proper remedies were afterwards employed, which occasioned his recovery.3

At this time all 'responses' were interpreted as cures, but in fact, many were down to the body's natural powers of recovery or periods of apparent remission in illnesses.3 Notwithstanding, these 'cures' were often faithfully repeated from textbook to textbook, sometimes over scores of years.

Fifty years later self-experimentation by Dr Alphonse Leroy led to the element's reputation for restoring or enhancing sexual potency. Leroy swallowed a dose of three grains of phosphorus, again in an opium substrate:

For two hours he was in a critical situation and took quantities of cold water until the uneasiness passed off. His urine became very red. On the following morning his muscular power doubled, and he experienced an almost intolerable venereal irritation.

This report chimes with an observation made by the French chemist Bertrand Pelletier, undated but probably a little earlier:

A drake and several ducks having drunk from a basin containing a solution of phosphorus and copper, died. But the male bird has such an irresistible propensity to 'tread' the females, that he died the first.4

Given that phosphorus poisoning causes abdominal pain, renal and haematological injury, it is perhaps not surprising that Leroy's urine turned red, and that he suffered 'venereal irritation' as a result of passing blood clots. We speculate that sexual urges would have been the last thing on his mind.

Even these early practitioners recognised the danger of poisoning their patients with elemental phosphorus. Writing in 1802, S. L. Mitchill and E. Miller mixed enthusiasm with caution:

Phosphorus, whose use was introduced into medicine about 50 years ago, is known as the most powerful, exciting remedy which we possess. (It is used). in all cases where a high degree of nervous debility persists, in nervous fevers... impotence virilis, epilepsy, arthritis and in cases of persons poisoned with lead and arsenic... Experience has shown that the application of this remedy requires the utmost caution; and it may sometimes prove very dangerous (causing) a vehement inflammation in the stomach and bowels.often terminating in death.5

Mitchell and Miller advised that no more than one grain should be taken per day. One of their preparations involved emulsifying the element with sweet almonds and then diluting down with 'spiritus nitre dulcis' (ethyl nitrite). Similar mixtures (but containing a much reduced phosphorus content) were still being recommended for impotence as late as the end of the 19th century. J. W. Howe enthused in 1887:

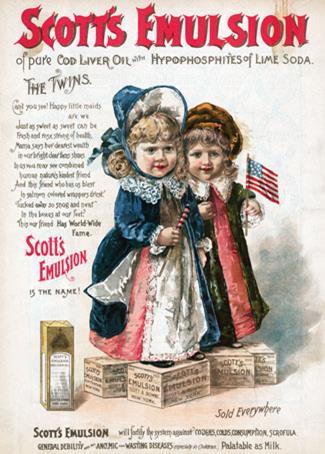

It is a powerful stimulant to the genital organs. It increases the desire for sexual intercourse without producing any local irritation of the genital apparatus. It also reduces the anaemic condition of the brain and furnishes it with that material that has been lost through excess..It must be given in minute doses and its effects carefully watched.. Half a grain of phosphorus may be dissolved in 1 ounce (=28 g) of cod liver oil, an half a teaspoonful of the mixture administered after meals until there is a manifest increase in the frequency and power of erections..As soon as symptoms of a disordered digestion appear, the administration should be discontinued for a few days and then resumed.6

In fact elemental phosphorus has no effect on virility, it will not restore potency to the impotent and it will have no positive effect on those taking it for coughs, colds, arthritis, gout or nervous debility.

The only condition that the element can 'cure' is pregnancy, but such cures (abortions) put the mother at considerable risk. Phosphorus, like arsenic, is slightly more toxic to the foetus than the mother. When, towards the end of the 19th century, it became difficult to obtain arsenic compounds, frantic mothers turned to phosphorus. And they had a ubiquitous source: the 'strike anywhere' matches contained yellow phosphorus in amounts from 1 mg upwards.

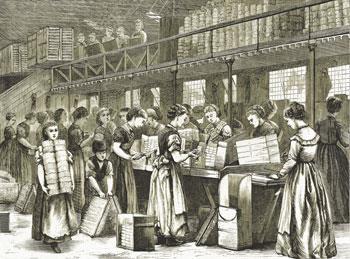

The women would scrape the heads off around 100 matches and consume the lot. Given the lethal nature of phosphorus it is not surprising that many attempts ended tragically. Swedish figures for the period 1851-1903 record over 1400 identified cases of such poisoning, of which only 10 mothers survived.7 It was this risk, together with the risk to the match workers of developing yellow phosphorus-induced necrosis of the jaw bone (phossy jaw) that led to its replacement by the much safer red allotrope, around 1900.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (consumption, or 'phthisis' when it was confined to the lung) was a dreaded disease in earlier times, with effective treatment by antibiotics not available until the 1950s.8 Until then patients generally died from the illness. In 1899 tuberculosis was responsible for around half of the deaths of those between the ages of 15 and 35.

Until the bacillus responsible for the disease was identified (Robert Koch, 1882) all sorts of causes were proposed: mental depression, breathing in other people's air, exposure to high winds, sexual excesses, living on wet soils and working in trades, such as needle-grinding, that exposed the lungs to particulate matter. Similarly many 'cures' were suggested, including cod liver oil, arsenic preparations, the inhalation of creosote fumes and many more - but all were useless. Among these 'cures' were sodium and calcium hypophosphites.

In the mid-19th century John Francis Churchill, a doctor working in Paris, hypothesised that those suffering from tuberculosis were unable to use inspired oxygen effectively because they lacked a key element. But what element?

Almost certainly Churchill would have known of phosphorus' affinity for oxygen and its toxicity, the latter precluding its long-term use. So he decided to use a phosphorus-containing compound with a strong affinity for oxygen. Hypophosphorous acid, HOP(O)H2, was well known for reducing several metal ions to the parent metals, itself being oxidised to phosphoric acid in the process. Somewhat surprisingly, its salts were moderately well tolerated by the human body. Churchill recorded in 1857:

The effect of these salts on the tubercular diathesis (ie predisposition) is immediate with all the general symptoms disappearing with a rapidity which is really marvellous. The hypophosphites of soda and lime are certain prophylactics against tubercular disease.9

Desperate patients were treated with proprietary hypophosphite preparations such as Dr McArthur's chemically pure syrup of the hypophosphites of lime and soda by desperate physicians who reported case after case of astonishing success.10 Eighteen years after the introduction of the hypophosphite regime, Chemical News reviewed the outcome from such treatment:

Dr Churchill does not profess that every patient was cured. In some the disease was already so far advanced that recovery was impossible; in other, carelessness of the patient, his manner of life, or the presence of special complications led to a negative result. But in a most decided majority of cases within reasonable limits, the theory has proved triumphant, and the patients recovered. Corresponding success has attended this method of treatment in the hands of other physicians, when the conditions laid down by the discoverer were observed, especially when the remedy was genuine, free from phosphates, carbonates etc which frustrate or modify its action.

The journal, though, inserts a note of caution:

The reception of so an important a discovery has not been encouraging. The hypophosphites have been used not according to Dr Churchill's suggestions, and he has been blamed for the resulting failures. In other quarters his remedies have been used in secret and the cures attributed to other causes.11

However, within 25 years the hypophosphite treatment for tuberculosis had vanished from textbooks, though the preparations were still in the pharmacopoeias.

It was becoming increasingly obvious that it wasn't working. Its 'successes' were possibly the result of the placebo effect, but more probably because pulmonary tuberculosis often goes into apparent remission, at least for a short time, before re-emerging in more florid form. If a remission occurred, it was attributed to the hypophosphites. And if it didn't, then excuses were made for their non-action.

In addition, another treatment was gaining momentum. Robert Koch cultured the tuberculosis bacilli in a broth with glycerol as an additive, evaporated the mixture at 100oC and filtered it to give a product he named 'Tuberculin'. This was hailed as a revolutionary treatment and, despite no firm evidence that it was effective, it enjoyed a 20-year cruel popularity from 1890.

You can still buy hypophosphite remedies over the counter. The Anglo-French Drugs Industry (an Indian company) markets Maximin Forte Syrup. Each teaspoonful contains 82 mg of calcium hypophosphite. But there is no mention of its use against tuberculosis but rather:

As a supplement to prevent deficiency states, to strengthen immunity and prevent recurrent infections in both paediatric and geriatric populations.

A glowing element

Phosphorus is unique among elements in first being discovered in human urine. The glowing substance must have been an extraordinary sight for Brandt and the early finding of high levels of phosphorus in brain tissue would have reinforced its mystery. No wonder that it was later promoted as a 'brain food'. Indeed, Coca Cola was initially marketed as a brain tonic, owing to its phosphoric acid content. However, the complexity of phosphorus' role in the brain remained little explored until the work of another German, Johann Thudichum, in the late 19th century. And his first major treatise was on the pathology of urine.

Alan Dronsfield is emeritus professor of the history of science in the school of education, health and sciences, at the University of Derby, Derby DE22 1GB.

Pete Ellis is professor of psychological medicine at the School of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Otago, Wellington, PO Box 7343, Wellington South, New Zealand.

Further Reading

We recommend John Emsley's text as an excellent overview of the chemistry of phosphorus in a general, medical and historical context.1 All the pre-1900 references listed may be downloaded, free of charge, from the Internet. Wikipedia has a useful article on Brandt and the extraction of phosphorus from urine.12

Related Links

Hennig Brand

References

- J. Emsley, The shocking history of phosphorus. London: Macmillan, 2000.

- R. Hooper, A new medical dictionary. Philadelphia: M. Carey & Son, 1817.

- A. T. Dronsfield, P. M. Ellis and A. Battistini, Ed. Chem., 2004, 41 (6), 162.

- F. Magendie, A formulary for the preparation and medical administration of certain new remedies, 2nd Edn. London: John Churchill, 1836.

- S. L. Mitchill and E. Miller, The medical repository and reviews of American publications in medicine and surgery . New York: T & J Swords, 1802.

- J. W. Howe, Excessive venery, masturbation and continence. New York: E. B. Trent, 1887.

- E. Shorter, Women's bodies: a social history of women's encounter with health, ill-health, and medicine. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1991.

- A. T. Dronsfield, T. M. Brown and P. M. Ellis, Ed. Chem., 2004, 41 (6), 151.

- J. F. Churchill, Dublin Hospital Gazette, 1857, 4, 252.

- J. A McArthur, Consumption and tuberculosis: notes on their treatment by hypophosphites. Boston: Alfred Mudge & Son, 1880.

- Anon, Chemical News, 1875, 31, 24.

- text

No comments yet