The Higher Education Academy (HEA) Physical Sciences Centre has been finding out what chemistry undergraduates and their lecturers think about the teaching and learning experience in higher education? Focus groups, interviews, and open comments from a questionnaire provide some useful insight for prospective students, chemistry departments and employers.

-

Feedback from staff and student focus groups provides useful information on the undergraduate teaching and learning experience

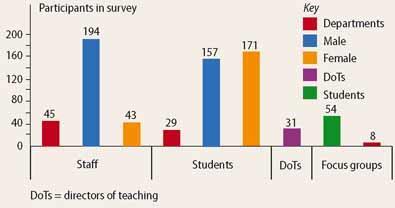

In 2007-08 the Higher Education Academy (HEA) Physical Sciences Centre sent questionnaires to staff, students and directors of teaching (DoTs) in university chemistry departments in England and Scotland. Students from all four years of BSc and MChem/MSci courses participated in the survey (Fig 1). The results of this research were published in a report, Review of the student learning experience in chemistry, in July and provide a baseline from which departments can develop their teaching.

In addition, volunteers were invited to three staff and student focus groups and four student interview groups (Fig 1). While material from the focus and interview groups, and from open comment boxes on the questionnaires, was considered too idiosyncratic to include in the survey report, nevertheless some interesting and pertinent points of view were expressed. These are worthy of a wider audience, and are the focus of this article.

Staff concerns about incoming students

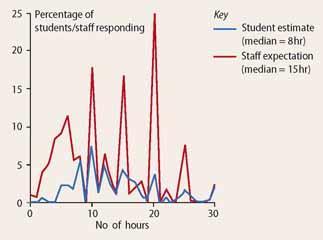

There was a strong consensus among the staff that today's students are not well prepared for the learning approach that they encounter on a chemistry degree programme (Fig 2). The fundamental problem seems not to be the range of ability, nor the variability in the A-level (or equivalent) specifications studied - though both cause difficulties for teaching staff - but rather the difference in teaching methods between schools and universities. Universities expect independent learners, whereas schools - aiming for high examination grades - use a teacher-led approach. Staff find that many incoming students have difficulty organising their time, taking notes, and prioritising their learning without detailed feedback on their performance.

Students agreed that A-levels rely too much on remembering facts, rather than acquiring the basic chemical understanding they need to start a chemistry degree. Most of them found assessment regimes at university different from their school experience - at school, teachers taught them how to pass exams, at university they had to work out for themselves what is needed. However, some students also said that university staff don't help them to become independent learners, giving little encouragement through the course.

Modularisation of A-levels is another grouse. Staff commented that this has led to students having patchy subject knowledge, and a pigeonhole mentality, whereas departments need students with more open minds who are able to interrelate different aspects of the course. But modularisation is also a feature of degree courses, and staff generally believe that the proliferation of 10 credit modules has led to over assessment.

Poor practical skills of students were also a common problem for university staff. Many students agreed that their schools had not given them enough laboratory work to acquire the skills needed to do first-year experiments confidently, and some commented that there were too many demonstrations and not enough hands-on experimental work.

A low level of mathematical skills of incoming students is another frequent complaint, with some staff believing that mathematics is not always taught in schools to a suitable level for university science. 'Remedial' maths courses are offered by most departments, even for students with A-level maths. However, students who have done maths sometimes find these courses boring while those who haven't got A-level maths find them intimidating especially when they are in the same classes as students with better maths skills than themselves. One department that demands A-level maths as an entry requirement rejects more than 40 per cent of applicants, but thinks it is worth it. However, in contrast to staff, some students were not convinced that a good working knowledge of maths is important for chemists.

Students in the department

Once on the course, students' work ethic and attitude are variable. Staff find that students often underestimate how hard they will have to work on a university chemistry course, and said it is difficult to get them to become self-motivated learners and put in the hours of private study that they expect (Fig 3). Some students agreed, finding it difficult to balance academic work, family, friends and hobbies or societies because of the demands of the course.

There was a feeling among staff that students don't always take the first year seriously. They tend to rely on information they can get quickly on the Internet, for example, rather than taking time to learn basic facts and information. Some staff suggested that a higher qualifying score to move from the first year to the second year might discourage this attitude. However, against this argument, some students find they need time to adjust to university life, and a policy where scores gained in the first year do not contribute to the overall degree grading was considered to be fair. Students then have an opportunity to settle in and learn from their mistakes without being penalised.

While many departments have adjusted their first-year modules to meet the needs of a variable student intake, for some this remains a challenge. Some staff find having to cater for the needs of less able students - who some feel should not be at university - jeopardises the opportunity for developing the full potential of the more committed and able students. They said there is a limit to what can be done, and it is only the financial models that force departments to adopt policies that allow under-achieving students to stay on.

Although most students find that working in the laboratory is a 'fun and friendly' time, they do not like the extra questions given on top of the practical work, and what they consider to be the excessive amount of writing-up required. Students complain that actual laboratory skills are not assessed, since practical marks are based almost entirely on written reports.

What makes a good lecturer?

Students say that good lecturers show a depth of knowledge in their subject, deliver it with passion and at a pace that allows them to understand the material and to take a good set of notes. They added that writing on a board or OHP keeps a lecturer at an appropriate pace for them to understand the material and take good notes.

Students agreed that it is better if lecturers don't try to put too much into each lecture, but spend time explaining the more complex ideas. Good lecturers initiate and maintain interaction with the students, and check students' understanding as the lecture proceeds. They include examples and exercises to aid understanding, and are happy to be interrupted for questions or clarification. However, students were critical of lecturers who go off at tangents to the main course themes.

Although all departments now use educational technology, good traditional teaching is still appreciated by students, and most staff were not convinced that any of the new technology helps students to learn any better. Mentions of the medium used for teaching are rarely seen in student evaluations, except in response to specific questions, because lecturers are seen to be good (or not) regardless of their method of delivery. Students found that PowerPoint presentations often have too little or too much detail on them, and some lecturers rush through their slides too quickly for students to read and appreciate the information. If PowerPoint notes are to be of any real use to students they need to be accessible on the university's virtual learning environment (VLE).

When staff were asked what they thought might make them better teachers, their answers reflected the pressures they are currently under. There was a definite sense that the research assessment exercise (RAE) distorts the relationship between teaching and research. Students get the impression that for some staff lecturing is incidental to their real job in research, and so teaching is not their priority.

Many staff would like to have time available to reflect on their teaching, and opportunities to learn to use new teaching techniques and technology. Before this could happen there would have to be more acceptance that teaching and learning is a valid form of scholarship, and more recognition of teaching excellence, through promotional opportunities and internal awards.

Students enjoy good working relationships with their lecturers, especially where the 'open door' policy has become a recognised part of the feedback system. They are positive about tutorials, and prefer them to be planned with work set.

Staff are generally more approachable than students might think at first, and it is more likely that in early years students are nervous of approaching staff, rather than staff being unwilling.

Work placements

The opportunity to spend some time in industry is eagerly taken by many students, and is highly regarded by most departmental staff and employers. However some students think the benefits can be overrated, especially if they have to spend time in an unsuitable workplace.

Not all students feel it is necessary to commit a year to working in industry. Shorter periods, they agree, could give the benefits without the problems. Students would also like other chances to make links with companies, and visits by employers, to get them thinking about what sort of career to follow.

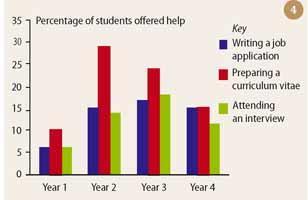

However, not all staff think the department should prepare students specifically for employment, nor do they agree that they should provide their students with the essential requirements for obtaining a job (Fig 4). Some students support this view, considering their main aim at university is to get a good degree.

Staff were more keen to support the development of a new curriculum that would improve the quality of graduates by encouraging critical thinking and analysis to a greater extent. Such a curriculum might move from being content-driven to skills-driven, and might involve more active participation by students. It would need to be flexible enough to tailor appropriate programmes for different outcomes. Assessment would follow guidelines understood by both staff and students, and designed to match learning outcomes, even to the extent of removing question choice from examinations, to cover a greater spread. The curriculum would be more relevant, and less modular, perhaps having just one examination at the end of each year.

Other suggestions for improving the student learning experience included: removing the walls between the organic, inorganic, and physical divisions (to encourage more synoptic thinking); greater harmonisation between theory and practice, lectures and practical work; and better coherence between the teaching input of different members of staff. There was the suggestion that the curriculum ought to include philosophy of science (to help students understand the process of scientific thinking), chemistry in context (to see applications of chemistry in the real world), the public understanding of science, and the use of scientific information. Although the introduction of problem-based learning within a chemical context has added variety to the learning experience, it has had a mixed reception. Some students like the freedom of resource-based modules, but others find this approach rather challenging, and have learned less as a result.

The views expressed here could be dismissed as anecdotal. Nevertheless, they were held strongly enough for participants to be willing to air them in open discussion, and reflecting on them could lead to an enhancement of your students' learning experience.

Copies of the report are available for download from HE Academy website or as hard copy from Liz Pickering, Administrator, Higher Education Academy Physical Sciences Centre, Chemistry Department, University of Hull, Hull HU6 7RX.

Michael Gagan is a consultant in the HEA Physical Sciences Centre, where he can be contacted.

No comments yet