Selecting the right chemistry course and the right institution are paramount in a prospective chemist's life

-

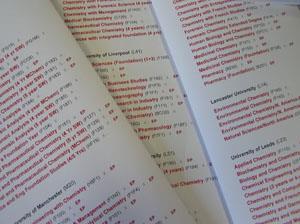

There are over 700 HE courses on offer with 'chemistry' in their title

-

Students need to be made aware of what the various labels mean

Selecting the right chemistry course and the right institution are paramount in a prospective chemist's life. An awareness of the jargon used in the description of degrees as well as knowing where to look for information, opinion and comment will be crucial to the potential chemistry student. Knowing how the application procedure works, in both the ideal and worst case scenarios, is also important.

In 2007 the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS)1 listed 213 courses with chemistry (as a single subject) offered by 47 universities. If you consider all courses with the word chemistry in the title this rises to 738 courses (at 68 institutions) - a bewildering variety indeed. However, there are in fact only two main degree types on offer. These are:

- bachelors qualifications (BSc), which typically take three years. BSc graduates are eligible for member-ship of the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC); and

- undergraduate masters degrees (ie MChem or MSci), which are four years' duration and may carry RSC accreditation for professional recognition in the form of Chartered Chemist status (CChem).2

Increasingly students are taking the MChem/MSci qualification if they want to pursue a career in the chemical industry or go on to do a PhD. Indeed some universities will not take a BSc graduate directly onto a PhD programme. This implies that a student needs to know what they are going to do after graduation even before starting a degree.

Most universities, however, will allow students to transfer between MChem/MSci programmes and the corresponding BSc programmes, typically up to the end of the second year, providing they can meet specific academic criteria. Nevertheless, it is worth students putting as much effort into picking the right course first because motivational and psychological factors can complicate even the most straightforward course transfer.

More labels

Watch out for degrees with the 'EuroBachelor' (EuroBSc) label. These are likely to become more commonplace as Europe attempts to unify the format of degrees by 2010 (under the 'Bologna agreement').3 Currently, a EuroBSc is academically equivalent to a BSc, but is possibly better recognised across Europe (an attribute that is not yet proven).

There are also single or combined honours courses, or the more applied type of chemistry courses (each of which might be at BSc or MChem/MSci level). What course students opt for is subjective but distils down to two key points:

- what mixture of academic subjects will keep them interested and motivated in their studies; and

- how will the qualification help them achieve their initial career ambitions.

Applied chemistry courses focus early on one particular area of chemistry, eg colour, food, forensics, materials, polymers etc. While many are excellent courses they are, arguably, too focused which might limit career options. Indeed, some industrialists and professional bodies make a point of saying that they prefer prospective employees to have a first degree in chemistry rather than a more specialised qualification.4

Combined honours degrees (also called joint honours) are labelled 'chemistry with X', where X is a second subject taught alongside chemistry in every year of the degree. A graduate of these degrees will have academic strength in two subjects, which is recognised in the name of their degree. However, applicants for these degrees should check the proportion of chemistry taught in each year of study because this will vary from one course to another. Degrees that are perceived by employers as a dilution of the main subject may not be considered as appropriate entry qualifications to some careers.

Single honours degrees in chemistry also differ from one institution to another. Chemistry is not the only subject studied - most will offer a variety of subjects in the first and second years. Such courses comprise core chemistry courses (to be taken by all) along with more core or elective subjects (representing student choice). Some universities offer courses that serve to fill in gaps in pre-university education - for example, in maths, physics and/or biology. The difference between single and combined honours is that the 'non-chemistry' studies typically stop at the end of the second year.

It is worth noting that details of all the courses taken throughout a degree (and the assessment outcomes) will be available to prospective employers - under the Bologna agreement universities will be required to produce full transcripts (courses and grades) for their graduates. Thus degree titles that include the name of the second subject specialisation might lose any impact they may once have had.

Work experience

Another area where universities differ is in the opportunity for work experience. Some offer 'sandwich' courses in which a student will spend a period in industry that is not formally assessed. More commonly universities include, as part of MChem/MSci programmes, an assessed placement. This might be clear from the degree title, for example, 'chemistry with industrial experience'. (These 'chemistry with X' degrees are not typical of combined honours courses, which are made up of two subjects. They simply bring together chemistry with work/research experience.)

Other universities offer placements in all, or a subset of their MChem/MSci degrees. Close consideration of the diversity of placement type - scientific content, location, finance, its scientific quality, local supervision and remote academic support, and assessment requirements are important considerations for any student looking at these degrees.

Available information

What then are the key sources of detailed information and guidance available to students? Clearly, teachers, careers coordinators, family and friends are invaluable sources of information, though each will have their own experience which influences their opinions (no bad thing but perhaps the student applicants are not aware of it). University league tables are another useful resource but their conclusions should be treated with care given the different treatment that each publication applies to the same data.

University-level and course-specific brochures are readily available and will often be provided direct to students who are part of the UCAScard scheme.5 In addition, UCAS asks that universities provide 'entry profiles' for their courses which UCAS hosts on its website1 (look for them on the course search facility) - a useful central resource for all applicants which can be used as the entry point to the web pages for each institution. A word of advice - always go to the department's website because this usually provides more comprehensive information on its courses than the central university website. The RSC also has extensive information on its website about what is available and what options are open to students interested in chemistry in HE.6

A really useful resource is the output from the National Student Survey.7 Graduating students from across the UK are asked to fill in a comprehensive questionnaire relating to all aspects of their experience. These data are collated centrally and are provided to all via the Teaching Quality Information (TQI) website8 along with other information about Higher Education. This student-led view of university life is a useful counterpoint to information provided by the university. More recently prospective students have started using chat rooms, like MySpace and The Student Room,9 to pose questions to existing students.

Even with all this information there is no substitute for making a personal visit. Most universities now host open days for Year 12 students before the UCAS application process starts as well as during the application cycle. The former events have taken on an increased importance for prospective students in recent years and have certainly played a major part in their ability to short-list courses and in some cases prioritise them as well. If for any reason a student cannot attend an official pre-UCAS visit they can contact the undergraduate admissions tutor (UAT) of the department to see if a visit can be arranged.

The application process

In 2007-08 the number of courses that students can apply for changes from six to five, which places a premium on getting the course choices right. One thing students need to consider is whether to use up all of the choices available on the UCAS form when first applying. It is not mandatory to do so and it is often useful to leave at least one selection empty to allow for an application to be made at a later date based on information picked up in the early part of the application year.

Provided that an application is made to a chemistry course by 15 January of the application year it will be considered on a level playing field with all other applications received up to that date (the exception is applications for Oxbridge and medicine, which are required by the previous 15 October). Applications may be considered when received after 15 January but the UAT is not required to consider them according to the same criteria as those submitted before the deadline.

Having chosen the course and the university, students apply through UCAS online. The application will eventually wind up on the UAT's desk. The student's prior academic record and current portfolio of study are clearly important but so is the student's personal statement. It is crucial that it is error free and demonstrates good written communication skills. One of the things we look for in the personal statement is the applicant's ability to evaluate what they have learnt from their life experience to date and to describe this with clarity. UATs want to know how an applicant has developed on the basis of what they have experienced rather than simply reading a list of experiences.

The outcome of the UAT's deliberations depends very much on the policy of each chemistry department. Some will make an offer to an applicant on the basis of the content of the UCAS application and invite the student to visit the department. Others will invite students to the department (with or without a formal interview) and only consider making an offer afterwards, and some will base the decision to offer a place on an interview held during the visit.

It is unwise to judge a department on the style with which they go about filling places on their courses. However, applicants should rightly expect to have clear information on the selection process being used and might also want to ask the UAT for an explanation of the process that he or she uses. Whatever method is used by the UAT the decision comes down to whether an applicant has the knowledge base and skills set to allow them to fulfil their potential on that particular degree programme.

The dialogue between the applicant and the UAT may continue up until early May at which time most students will have identified a first (firm) and second (insurance) choice. For those who have not had an offer there is a process called UCAS Extra that allows students to find a place on a course for which they had not originally applied, though not all courses will be available through this route.

The waiting game

After concentrating on their courses and final examinations, the students have to play the difficult waiting game until publication of A-level results in the UK in mid-August (other pre-university qualifications are available at other times and will be responded to as soon as they are available). Students who meet their academic offers will receive immediate confirmation of their place. Those who do not meet their offer might still find themselves offered a place after their situation has been referred back to the UAT.

It is extremely important that applicants get in touch with the UAT of their firm choice to confirm their status. Second chances come in the form of insurance places and also with the clearing process so a student who does not make their first choice will still have options open to them.

A subject must interest students if they are to do well. When looking at courses they must untangle the titles and 'jargon' and look at the detail of the curriculum and experience offered, and ensure that this degree will hold their interest for its full term. Whatever happens, the final choice has to be made by the student who is going to have to deal with the future highs and lows arising from their decision.

Dr Jeremy Hinks is undergraduate admissions tutor for the school of chemistry at the University of Southampton, Highfield, Southampton SO17 1BJ.

What questions to ask relating to the course

- What is the chemistry curriculum in the first year?

- How does the curriculum and its delivery take into account the academic background of the students starting the course?

- What is the nature of the practical tuition in the early years?

- How does the practical work support the teaching of theory?

- What academic support is there for the development of skills in maths, physics and biology - subjects that intersect with parts of the chemistry curriculum?

- What are the wider opportunities for study outside of chemistry?

- What flexibility is there in changing from one degree to another if I find that I have made the wrong choice in the first instance?

- How many students do not successfully complete the first/second year of the course?

- What diversity is there in terms of areas of specialisation in chemistry in the senior years?

- How is the practical research component of the course arranged: diversity of projects, allocation of projects, level of supervision, quality of facilities and format of assessment?

- How effective is the interaction between the undergraduate and postgraduate schools?

- How effective is the feedback provided on assessed work - coursework and examinations?

- How are students supported in their time on the course with respect to academic and pastoral care?

- What are the opportunities with regard to work placements either as a part of the degree or as an extracurricular activity?

- What consideration is given to teaching the skills (beyond subject knowledge) that will be important on entering the job market?

- What is the level of success of graduating students in taking the next step beyond graduation and where are your graduates employed?10

Also of interest

Accredited Courses

The RSC accredits certain degrees as satisfying the academic requirements for RSC membership

Choosing courses

All the information you need to make the right course choices

Careers information for students and postdocs

Advice on careers, further study and how the RSC can help

Related Links

UCAS

UCAS is the central organisation that processes applications for full-time undergraduate courses

Bologna Process

Intergovernmental initiative which aims to create a European Higher Education Area (EHEA) by 2010

Forensic Science Society

Careers

UCAS card

UCAS Card will allow you to access information about higher education as well as individual universities and colleges

National Student Survey

A survey targeted mainly at final year undergraduates

Unistats | UK university and college search, reviews, statistics | UCAS points

Unistats is the official website to help you make an informed choice when deciding which university or college to apply to. Unistats brings together authoritative, official information in one place, in a way that is not available on any other website

The Student Room

Forums for all levels

No comments yet