Endpoint: Vanessa Kind has the last word

Michael Gove's gyring and gimbling will surely only have one result - perpetuation of a cycle of poor understanding and low achievement in chemistry in state secondary schools.

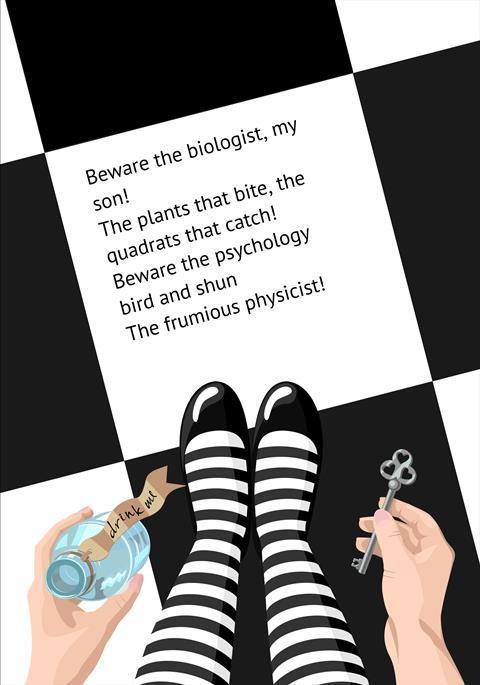

'Twas brillig and the slithy Gove

Did gyre and gimble in the House

All mimsy were the ministers

And the Training and Development Agency out-dowse

'Beware the biologist, my son!

The plants that bite, the

quadrats that catch!

Beware the psychology bird and shun

The frumious physicist!'

He took his chemical sword in hand:

Long time the green-leaved foe he sought -

So rested he by the periodicity tree,

And stood awhile in thought.

And as in groupish thought he stood,

The Biologist, with dipoles of flame

Came electroning through

the elemental wood,

And energised as it came!

One, two! One, two! And through

and through

The chemical blade went analytical-snack!

He left it dead and with its head

Went ionically back.

'And has thou slain the Biologist?

Come to my arms, my orbitalish boy!

O dativeous day! Bondooh! Hooray!'

'Twas brillig, and the slithy Gove

Did gyre and gimble in the House

All mimsy were the ministers

And the Training and Development Agency out-dows

(with apologies to Lewis Carroll)

'Un' chemistry teachers

Ensuring state secondary schools get good chemistry teachers remains an ongoing concern. The present government in England and Wales plans to resolve this by raising academic standards of graduate entrants to teaching,1 on the assumption that possessing a 'good' Bachelor's degree, ie 2:2 or better, equates to 'high quality' subject knowledge. This sounds laudable, as a teacher with 'good' subject knowledge is more likely to teach successfully than one deemed to be 'weak'. However, reality indicates this isn't so clear cut.

At present, around 55% of science graduates in teacher education have degrees in biology, or 'biology related' subjects, such as biomedical sciences, ecology, genetics or environmental science. This 'biological majority' has persisted for some years, despite various (expensive) attempts at redress. Further, most have not studied chemistry since they were 16; and took 'Double Award' Science 16+ courses, in which physics, chemistry and biology are squashed into two subjects-worth of study, restricting content to two thirds of a GCSE. So, the chance that non-chemistry, and, more specifically, biology based graduates starting teaching have 'good' chemical knowledge is, in fact, small.

Flaws in the basics

Evidence supporting this is apparent in data I collected over six years from around 270 academically well-qualified graduates starting teacher education at Durham. Many had flaws in their understanding of basic chemical concepts. For example, about a third said that a single copper atom is coloured; bubbles in boiling water contain air or oxygen; covalent bonds are weaker than ionic bonds so break more easily; and energy is released when bonds are broken.2 Less frequent, but strikingly 'non-chemical' ideas include: exhaust gases from a car have less mass than the original fuel (26%); hydrochloric acid contains hydrogen chloride molecules (15%); acids and metals react by 'swapping partners' (15%); and a precipitate and solution have greater mass than the mass of the two original solutions (13%). The 76 chemists showed significantly better understanding than physicists and biologists, suggesting chemistry (or chemistry related) degrees confer better subject knowledge. Nevertheless, simply 'having a good degree' does not help, as teacher educators in universities know. Any self-respecting initial training programme sends trainee teachers into schools after checking and sorting out misconceptions.

Better subject knowledge

But here's the rub: the government's other strategy for enhancing recruitment and quality is to move teacher education to schools, reasoning that learning 'on the job' is more effective than spending time in universities. However, evidence shows school based systems leave trainees underprepared for classroom life.3 Also, experienced teachers, responsible for training, are bound to curricula, school context and general behavioural concerns,4 not improving subject knowledge. Thus, in school no line of responsibility for developing 'good' subject knowledge exists. Most science teachers in state secondary schools are biologists, so who is able to improve new entrants' chemical knowledge anyway? My data suggest many graduates received poor quality chemistry teaching, and were examined at 16 for recall of rote-learned generalisations, not conceptual understanding. Michael Gove's gyring and gimbling will bring one result - perpetuation of poor understanding and low achievement in chemistry in state secondary schools. Unless, of course, someone slays the biologist.

What do you think?

What are your views on the topic? Let us know by email, Twitter or Facebook.

Vanessa Kind is Senior Lecturer in Education at Durham University and Director, Science Learning Centre North East

References

- Department for Education, The importance of teaching. London: The Stationery Office Ltd, 2010 (http://bit.ly/imptteach accessed January 2012)

- V Kind, J. Sci. Teach. Educ., submitted

- W R Houston in Handbook of research on teacher education, ed M Cochran-Smith et al, 3rd edn, ch.22, p388. New York, US: Routledge, 2008

- H Arzi and R White, Sci. Educ., 2008, 92, 221 (DOI: 10.1002/sce.20239)

No comments yet