Endpoint: Stuart Walker has the last word

The outcome of the debate into how the UK's energy is produced has made nuclear energy headline news. The Government has made clear its support for nuclear energy by backing a new generation of fission reactors which will provide a significant proportion of the UK's energy needs in the future. However, 50 years ago, another type of nuclear energy was headline news for different reasons.

A star is born

On the 25 January 1958, the press crowded into Hangar 7 of the Harwell nuclear research establishment, near Oxford, to hear news of a revolutionary scientific discovery. Nuclear physicists at Harwell had heated deuterium gas to ca 5 × 106 °C inside a torus, code-named Project Zeta, in an attempt to recreate the nuclear fusion processes inside the Sun. The scientists announced that free neutrons had been detected during these experiments, suggesting that nuclear fusion had been achieved inside the torus.

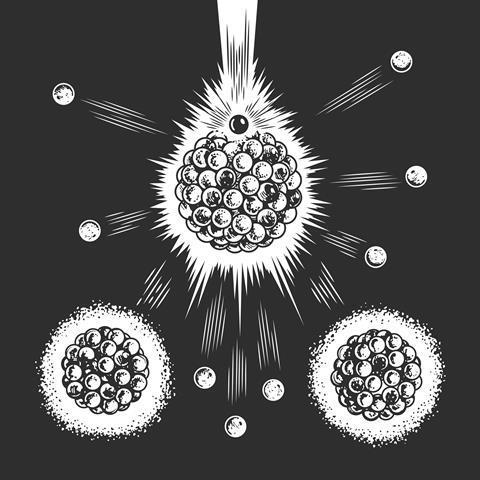

Free neutrons are a product of the fusion of two atoms of deuterium:

21H + 21H → 32He + 10n + Energy

When questioned, director of Harwell, Sir John Cockcroft said he was 90 per cent sure that nuclear fusion had occurred. The press seized on these preliminary results, desperate for good news following the 1956 Suez crisis that highlighted the UK's position as a declining world power. Furthermore, US and Soviet nuclear rivalry and the launch of the first man-made satellite, Sputnik, only exacerbated Britain's tenuous position on the world stage.

The headlines made much of the fact that a controlled fusion experiment recreates the processes occurring inside a star, 'A Sun of our own' and 'Britain's H-men make a Sun' and 'The mighty Zeta provides limitless fuel for millions of years'. Reports predicted that this form of nuclear energy would eventually make other forms of energy obsolete.1

Champagne supernova

With the sound of popping champagne corks still reverberating around Hangar 7, the first signs of trouble soon emerged. Further analysis of the free neutrons produced during the heating of the deuterium revealed that many of them had been produced by the heating process itself, so no significant nuclear fusion had in fact occurred.

Nuclear physicists went from being almost worshipped in the press for their achievements in building the hydrogen bomb and instigating the first British nuclear power station, to being reviled not only for Project Zeta's failings but also for the reactor fire that had occurred at the Calderhall nuclear power station during the previous year. In response, chief scientist at Harwell, Sir George Thompson commented that a viable nuclear fusion reactor could be developed in around 20 years. This quote no doubt spawned the commonly shared scientific joke that 'Viable nuclear fusion is always 20 years away'. The dream of unlimited energy from nuclear fusion was exploding.

Utopian dreams

The biggest promise to come from Project Zeta has yet to be realised. Nuclear fusion has the potential to provide virtually limitless amounts of energy without releasing any environmentally harmful byproducts. And the fuel for the nuclear fusion process, deuterium, can be extracted from seawater, a virtually limitless supply. Although Project Zeta did not live up to these heady goals, it was not without its successes.

The experience gained in high temperature plasma physics enabled UK scientists to confirm Russian claims of a superior type of nuclear fusion reactor, the tokomak, which later became the basis of the first significant controlled release of nuclear fusion power. In 1991 the Joint European Tokomak (JET) at Culham, only six miles from Harwell, produced 2 MW of power for two seconds. Although this is a long way from producing a working nuclear fusion power station, it demonstrated that it is theoretically possible (see Educ. Chem., 2006, 43 (3), InfoChem).

Producing energy from controlled nuclear fusion would supersede the new generation of nuclear fission power plants that are planned for the UK. However, with the new multinational fusion reactor, ITER, still in the planning stage, nuclear fusion reactors will not be meeting our energy needs in the near future.

Let's hope that one day the prophetic words of Bas Pease, one of the original Project Zeta nuclear fusion scientists, will put our current energy debate into context: 'It's limitless, once it works, it really will solve an energy problem forever'.

Dr Stuart Walker teaches chemistry at Ridgewood School, Barnsley Road, Scawsby, Doncaster DN5 7UB

References

- BBC radio 4 programme, Britain's Sputnik website

1 Reader's comment