How did horse meat remain undetected in the food chain for long enough to reach supermarket shelves? Ian Farrell investigates

In the UK we don't like the thought of eating horse meat, but it turns out that's exactly what many of us have been doing, even though we weren't aware of it at the time. Equally, recent tests have shown that those who don't eat pork for cultural reasons may also have been ingesting something they didn't want to. While neither of these examples of food fraud is hazardous to health, adulteration of food and drink can be dangerous: methanol in counterfeit vodka can cause damage to the brain and eyesight, while the addition of melamine to baby milk in China in 2001 caused scores of infant deaths before it was discovered.

Defence against the dark arts

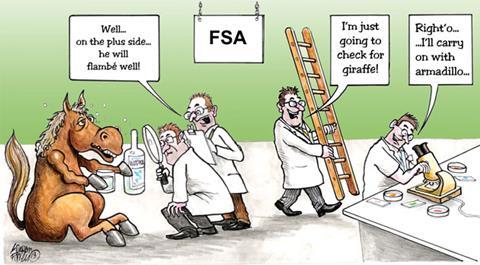

So what stands in the way of the food fraudsters, and protects the public from harm? The first line of defence comes in the form of the army of analytical scientists working for public analyst labs, private testing companies and government departments, like Defra and the Food Standards Agency (FSA). Using methods like real-time PCR and ELISA immunoassays scientists can detect traces of horse DNA at levels less than 0.01%, and horse meat protein at 1%. That's pretty good, so why wasn't horse meat detected earlier, and prevented from getting onto the supermarket shelves?

The reason the fraudsters got away with things for so long is that testing on its own is not enough to detect such crimes. Flying in the face of everything we've learned from TV shows like CSI, Dexter and Silent Witness, testing is targeted and specific. A machine or method does not exist that will simply identify the different animal species present in a sample, each one must be searched for individually, which means we have to know what we are looking for in the first place in order to find it.

Ever eaten giraffe?

Horse meat was found because that was what was being searched for, but where do we stop? Do we look for traces of giraffe? Zebra? Armadillo? It's impossible to test for everything, which is where intelligence comes in. If the analysts know what is likely to be used in the adulteration of foodstuffs, this can narrow the search by a huge margin, and increase the chances of detecting food fraud.

Intelligence can come from a variety of sources. The food industry itself is a good one, with companies reporting rumours that they have heard about competitors acting in an unfair way.

A knowledge of history is useful too: this is the third big horse meat scandal since the war, and what has fooled people once will undoubtedly fool them again.

No comments yet