John Emsley looks at the heavy metal that makes light work of tough jobs

Objects designed to impact on things, such as the tips of ballpoint pens, darts and even the noses of Polaris submarine nuclear rockets, are made of tungsten alloys.

Mystery mineral

There are several tungsten minerals, such as ferberite (FeWO4), scheelite (CaWO4) and wolframite ([Fe,Mn]WO4). World production of tungsten is around 74 000 tonnes per annum, with China producing almost 90%. The metal is also recycled, and this meets 30% of demand.

Tungsten was almost discovered on several occasions. In 1761, the German chemist Johann Gottlob Lehmann analysed a mineral referred to as tung sten (Swedish for heavy stone) without recognising that it contained a new metal. The Irish chemist Peter Woulfe examined it in 1779 and realised that it did contain a new metal, but got no further. In 1781, the Swedish chemist Wilhelm Scheele succeeded in isolating an acidic white oxide from the ore.

Two Spanish brothers, Juan José Elhuyar and Fausto Elhuyar, finally reduced the new oxide to the metal itself in 1783 by heating it with charcoal. Fausto wanted to call the new element volfram, which is still its name in Sweden, while Juan preferred tungsten, which became the name preferred name in England and France. In Germany, Spain and Italy it is called wolfram.

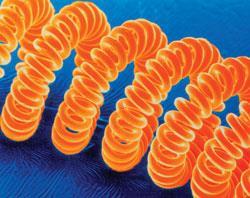

Tungsten is generally obtained as a dull grey powder, which is difficult to melt. As the pure metal it is easily worked, can be cut with a hacksaw and is very ductile (a gram of the metal can be drawn into a wire 400 m long).

Strong and flexible

Tungsten has played a key role in weaponry. By the end of the first world war, demand had soared to 35 000 tonnes a year. More recently, tungsten is being used in place of lead in bullets - the US Army have an oddly named 'Green Ammunition Program'.

In 1864, the Englishman Robert Forester Mushet found that adding about 5% of tungsten to steel produced a metal that was harder, stronger and could withstand red heat without deforming. Soon it found use in machine tools, allowing metal cutters to work much faster and last longer.

Tungsten is used for electric contacts, arc-welding electrodes and for heating elements in high temperature furnaces. High-speed steels contain around 7% tungsten and these are used for saw blades, punches, dies and other high impact devices. However, so-called cemented carbide tools are taking their place.

Tungsten carbide

Cermet or hardmetal (cemented carbide) is the most important use for tungsten and its main component is tungsten carbide (WC). It is made by mixing tungsten powder with pure carbon powder and heating to 2200°C. It was invented in 1923 by Karl Schröter.

Cemented carbide has the strength to cut cast iron and it makes excellent cutting tools for the machining of steel. It revolutionised productivity in many industries when it was introduced in the 1930s and that included ultra-high speed tungsten-tipped dental drills. Cemented carbide now accounts for 40% of the world production of tungsten.

Light and heavy

Pure metallic tungsten was used for the filaments of old style incandescent light bulbs. In 1903, W D Coolidge reduced tungsten oxide to the metal and then shaped this into thin rods that he was able to draw out into fine wire, an ideal material for filaments. Moreover, tungsten's vapour pressure is the lowest of all metals. This means that the filament did not evaporate and redeposit on the cooler parts of the light bulb.

As it is such a heavy metal, tungsten has been used as ballast for yacht keels, aircraft tails, and F1 racing cars. Fishing weights are now made from tungsten in place of the lead sinkers that were used. These were responsible for killing bottom feeding birds, who scooped up the weights and eventually died a slow death from lead poisoning.

Data file

Atomic number 74; atomic mass 183.84; melting point 3414°C; boiling point 5555°C; density 19.3 g cm-3. Its most common oxidation state is +6, as in WO3, WCl6 and WO42-.

No comments yet