Reminiscent of Who Wants to be a Millionaire voting systems, university lecturers can use electronic voting systems to monitor students' understanding and make learning more interactive for the students and the teacher

-

EVS can be used to engage large groups of students;

-

Students with limited chemistry knowledge find the systems useful in aiding their understanding

One of the major differences undergraduates experience during the transition to university is the style of teaching. In schools and colleges most students study Key Stage 5 subjects in relatively small, informal groups where teacher-pupil interaction is encouraged and two-way feedback occurs through question and answer type delivery. On starting in HE students are amazed by the sizes of the classes. For even a relatively small chemistry department with an intake of 60-70 students, biologists, pharmacists, and other first year undergraduates requiring chemistry can boost numbers in the lecture hall to around 200 or higher. In many universities class sizes of 400 are not unusual for first year groups where efficiency is crucial. Clearly the personalised classroom-style delivery is not practical and it is a brave student who shows his ignorance by venturing to ask a question in front of such an audience. In these environments learning can be a very passive process, the lecture acts as a vehicle for the conveyance of information and our students are expected to reinforce their understanding by 'self-study', a term, the meaning of which, many struggle to understand. The use of electronic voting systems (EVS) in such situations can vastly change the students' learning experience from a passive to a highly interactive process. This principle has already been demonstrated in physics, most notably in the work of Bates and colleagues at Edinburgh.1

These small hand-held devices, similar to those which have become familiar through programmes such as Who Wants to be a Millionaire can be used to provide instant feedback to students and teachers alike. Advances in technology now allow them to be used in a range of more sophisticated settings and comprehensive guides on use have been developed for even the most techno-phobic staff.

The changing face of HE

We have been involved in projects which comprise Strand 3.1 of the successful HEFCE funded programme 'Chemistry for our Future' (CFOF) managed by the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) from 2007-9. A key focus of the Reading and Southampton projects was to facilitate the school/college to university transition with the aim of improving retention and raising attainment throughout the course. Clearly such lofty goals involve a variety of different strategies and approaches, of which the use of electronic voting systems is just one. However, a thorough exploration of the effectiveness of EVS has demonstrated that the potential for these systems is not just limited to lecture situations and the advantages go far beyond simply stimulating interaction and keeping students awake!

It is important to recognise that the secondary-tertiary transition is not a new phenomenon, although it does appear that changes to teaching methods and assessment in schools, coupled with the differing expectations of today's students, have exacerbated the problem. In addition to this, HE has seen a massive expansion over the past 15 years, driven by the goal of 50 per cent engagement, which has led to greater diversity among our students. Most chemistry departments are becoming more sensitive to the different needs of their students; for example at Reading we have an established support programme for those students with 'non-traditional' backgrounds in chemistry. The appointment of 'School-Teacher Fellows',2 studies of secondary school teaching carried out in undergraduate education projects (coordinated through the undergraduate ambassadors' scheme3) and links with teachers such as through 'Chemistry Teachers Centres'4 have all highlighted to academics the changing face of the secondary student body. Additionally, the introduction of student fees in UK HE raises the stakes for departments, with high drop-out levels being untenable in today's world.

Institutions have also placed an emphasis on teaching methods which provide feedback to students, as this is a sensitive area for improvement in the National Student Survey. Additionally there is a strong drive for institutions to raise the profile of learning and teaching and particularly to include innovation in these fields. It is clear that these factors all act as incentives to incorporate and embed new learning technologies such as EVS in undergraduate teaching.

Applications of EVS

We have used EVS in a variety of ways to enhance teaching and learning at undergraduate level. Selected examples and outcomes are related below.

A-level revision activities

It is important for those of us who deliver first year courses to understand the knowledge undergraduates bring with them to HE. Although we can access A-level grades and specifications, this often bears little relation to the knowledge students actually bring with them to lectures. Long summer breaks, gap years and the modular teaching style of Year 12 and 13 courses may have eroded students' memories of key concepts and facts necessary for successful progression to HE.

At Southampton, in Year 1 we choose certain key topics for revision at the start of the year and students' performance is gauged by the use of EVS response in lectures. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this approach is valuable for reintroducing the topics and providing a platform from which to embark on the first year material.

Informal quizzes during lectures

There has been work carried out by educationalists in other subject areas, particularly in the US, on the benefits of EVS in supporting teaching and learning of material covered as part of a degree programme.5 Little published information is available on their application in teaching chemistry but we have been able to derive a positive correlation between EVS use and attainment.

At Reading, EVS have been used for the past two years throughout a core Part 1 inorganic chemistry module. The devices are used mainly for quick, mid-lecture quizzes which provide a natural break in the delivery and encourage students to reflect on their understanding and stimulate discussion with neighbours. The questions are delivered via Powerpoint and can be of a variety of different types, of which multiple choice is probably the most popular. The lecturer allocates a fixed time for receipt of answers and students respond using their voting devices. Once all responses are received, the software generates a chart displayed overhead showing the proportion of students with the correct answer (and incorrect answers) and highlights the correct answer. Students can assess their individual performance relative to the rest of the class and the lecturer can ascertain general understanding. A well-designed multiple choice question can be very informative about the nature of the misconceptions. The lecturer will then run through the correct answer, correcting any misunderstandings and providing valuable formative feedback. The voting devices are also used in this module for short, non-summative end of topic tests and for revision sessions. The particular handset type used in Reading can be used in the 'known mode' which allows students to input a personal identifier (name or student number). In this mode the handsets can be used for summative assessment in tests or in homework sessions where the scores of students are retained. The information can then be displayed or downloaded in a variety of ways. Individual student reports can be uploaded to Blackboard giving scores and feedback on correct and incorrect answers. Class results and averages can be stored in Excel with other assessment data.

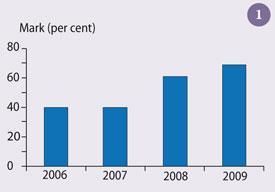

In the final Year 1 exam for this Inorganic module the average paper mark has increased from around 48.2 per cent in 2006 and 2007 to 58.1 per cent (2007/8) and 63.0 per cent (2008/9). The marks for the equivalent Part 1 Physical and Organic papers have remained roughly constant during this time. Furthermore, when specifically considering the three compulsory questions on the final exam which relate to the block of lectures in which EVS were used, the 2008 average was 61 per cent and the 2009 average 69 per cent, significantly higher than the average for the same section in 2006 and 2007 (see Fig 1). This indicates that knowledge from lectures which incorporate EVS is well retained. Although it is difficult to compare different cohorts of students over different years these results do seem to show an improvement on the section of the course in which EVS were used, particularly as the 2007/8 and 2008/9 cohorts showed a lower attainment in the other core exams.

Student perceptions

There are numerous reports of using EVS as a valuable learning tool8 to promote peer learning via discussion and our observations are that informal discussion certainly takes place and is stimulated by the use of EVS. Eavesdropping on conversations between students during sessions clearly shows that they are genuinely discussing the problems and theories behind them and this has clear ramifications for their learning. The use of EVS at both Reading and Southampton has been very well received by students and appears to have shown a positive effect on student attainment and learning.

Some comments from first year students after using the EVS handsets in lectures include: 'You know you can be honest because it's anonymous', 'testing my knowledge was helpful', 'they make you think in lectures', 'good for revision', 'easier to use than paper and more private' and 'good to be interactive'.

Questionnaire responses at Reading showed that 70 per cent found the use of EVS in lectures either enjoyable or very enjoyable and 65 per cent found them useful or very useful for checking their understanding in lectures. We have also used EVS quizzes in foundation chemistry teaching to students with only limited chemistry experience. Here we have found particular benefits for those students who typically find chemistry very challenging. Surveys of these students showed that over 70 per cent found them either useful or very useful for aiding understanding.

We attempted to determine the reasons why not all students are enamoured by the use of EVS and found that it is generally the stronger students who find them less useful. The reasons they gave questionnaire were that EVS waste time and are 'gimmicky'.

Other applications

Breaking the ice with new undergraduates

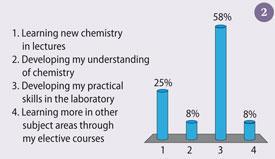

The first few weeks at university are an exciting time for new undergraduates, but can also be quite scary. Most departments have invested time and resources to help students through those first few weeks. At Southampton we use EVS in an introductory session during freshers' week to help gauge the mood of students after their first experiences of university life. Displaying the results by bar charts helps demonstrate to students that they are not alone in their apprehensions, and we are able to offer advice and reassurance where possible, as well as gaining a snap-shot of student feelings (Fig 2).

Both Reading and Southampton groups use EVS for chemistry quizzes in freshers' week which provide an ideal opportunity for team building and ice-breaking. At Reading students are teamed in 'mentor groups' with an established student or post-grad to help freshers feel at home. Prizes are awarded for the winning team with all participants getting consolation lollies. The power of such activities in helping new students establish links with their new department and peers should not be underestimated.

Surveys and evaluations

In an age where student opinion is becoming increasingly sought there is a danger of 'survey overload'. Students often find paper-based surveys tedious to fill in and the processing and presentation of the data is time-consuming and repetitive. Furthermore, many students simply ignore the form and so the data obtained is incomplete.

At Southampton, we have used EVS to collect course evaluation data from students at the end of a semester. A notable advantage over a paper survey was the instant collation of data into bar charts, with further processing possible using the EVS software. In addition, an overwhelming majority of the students (>95 per cent of those present) submitted answers to each question. The system used at Southampton is limited to multiple-choice questions (e.g. Likert responses), and does not allow alphanumeric responses, unlike some other EVS. Therefore, to supplement the EVS data we invited students to answer a series of questions in writing at the end of the session, which many of them did. In these cases, the quality of the written comments was higher than in cases where questions had been included on a survey form, perhaps reflecting the positive attitude of many students towards the idea of collecting the bulk of the data electronically. In a similar way, EVS were also used at Reading to collect data on student attitudes to various teaching methods and to gauge feelings about starting university as part of a "ReFreshers Week" activity mid-way through the first term. The anonymity of the system was vital in this situation and the immediate display of data allowed staff to respond to particular problems and introduce students to the various support mechanisms available to them at University.

Inspiring young people in outreach activities

EVS have been used successfully to inspire youngsters during outreach activities at both Reading and Southampton.6,7 Being easily portable we can take EVS into local schools to support the delivery of activities on topics such as the use of biofuels. EVS can act as ice-breakers, even with the most reluctant sixth-formers, who can offer opinions anonymously, and soon become engaged in the activities. EVS are also valuable for simple 'pub-quiz' type activities in schools where all age groups quickly make the link between using EVS and the popular TV show Who Wants to be a Millionaire.

The use of EVS is particularly appropriate for gauging the opinions of large groups in debating sessions. At Reading popular science topics such as GM foods and nuclear power have been discussed with pupils of a range of ages and abilities. Two teams of pupils research and formulate their arguments and audience opinion is surveyed both before and following the debate, with the winning team being decided by the swing of votes in their favour. Because the responses are anonymous, instant audience engagement is ensured.

Finally...

There are many reports of the use of EVS in undergraduate teaching. These mainly focus on their use in facilitating peer interaction and in formative assessment in large lecture classes. Our experiences using EVS confirm that they can be used successfully to engage students in large lecture groups and particularly to improve feedback in formative assessment. The anonymity of the system appears to be one of its most important features in encouraging students to contribute and interact with the lecturer and each other. However, we have carried out initial trials that indicate EVS may also have a use in tracking student progress and summative assessment.

The main disadvantages of the system tend to be practicalities such as time taken to distribute handsets. The software is easy to use and questions are easily incorporated into lectures, however, the onus is on the teacher to design appropriate questions to make EVS effective .

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the CFOF project officers from Reading, Dr Gan Shermer (now at the University of Bath) and Liz Tracey for their technical support and help.

References

- S. P. Bates, K. Howie and A. St. J. Murphy, The use of electronic voting systems in large group lectures: challenges and opportunities, New Directions in the Teaching of Physical Sciences, 2006, 2, 1-8.

- T. G. Harrison and D. E. Shallcross, The impact of Teacher Fellows on teaching and assessment at tertiary level, New Directions in the Teaching of Physical Sciences, 2007, 3, 77-78.

- M. J. Almond and E. M. Page, The Ambassadors, Educ. Chem., 2008, 179-181.

- See website

- J. R. MacArthur and L. L. Jones, A review of literature reports of clickers applicable to college chemistry classrooms, Chem. Educ. Res. Pract., 2008, 9, 187-195.

- D. G. Niyadurupola and D. Read, The use of electronic voting systems to engage students in outreach activities, New Directions in the Teaching of Physical Sciences, 2008, 4, 27-29.

- D. Read, Happy zapping in the classroom: enhancing teaching and learning with electronic voting systems, School Sci. Rev., 2010, 91, 107-111.

- E. Mazur, Peer instruction: a user's manual, San Francisco: Prentice Hall, 1997.

No comments yet