Including commercial awareness in undergraduate chemistry courses calls for an interactive teaching approach, says Samantha Pugh

Employers in the chemical and related industries consistently criticise UK chemistry graduates as lacking in business-related skills and commercial awareness outside of pure scientific knowledge. Transferable skills, such as teamworking, solving open-ended problems, oral presentation and efficient information retrieval are highly valued, but often identified as lacking.

Employers also seek graduates who have some understanding of the way businesses operate, as shown by responses to a survey conducted at the University of Edinburgh1 – one employer stated the case quite succinctly: ‘It’s rare that people use more than 10% of the science they know at any time with us. But what we need is for them to understand, interface and interact with people from other disciplines (commercial and technical such as engineers).’

In response to the Royal Society of Chemistry’s call for proposals to develop business skills resources for chemists in higher education (under the National HE STEM programme), the University of Leeds has created a new second year module called Chemistry: Idea to Market. The course is worth 10 credits (of 120 required for the year), and is designed to lead students through the various stages of taking a new product from concept to market. The main emphasis is on developing new products within a larger company, rather than entrepreneurship and starting new businesses, which is well-supported by other resources.

Business topics are explored in context, using case studies that give students the freedom to develop areas that interest them. Such problem-based case studies are effective learning tools,2,3 and the nature of the topic lends itself to this teaching method. Similarly, moving away from a lecture-based approach to facilitated workshops is a more successful way of developing transferable skills and other attributes employers desire.4

While most employers say that they would like graduates to be more ‘commercially aware’, the challenge is defining what this actually means, and designing learning materials that are flexible enough to be valid in the varied career paths that chemistry graduates pursue.

The syllabus for the module covers many generic aspects of new product development for the chemical and allied industries. The facilitated workshops introduce students to the themes and skills that are required to deliver the project, and are split over four themes:

- Project management, including methods such as work breakdown structures and risk management

- Intellectual property (patents and trademarks)

- Marketing – both as a discipline and introducing specific market analysis techniques such as SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats), PESTLE (political, economic, social, technological, legal and environmental factors) and the Boston Matrix

- Scale up – including HAZOP (hazard and operability studies), HAZAN (hazard analysis), risk assessment and regulatory issues.

Industrial input

Involving employers in both the development and delivery of the curriculum enhances student employment prospects more than embedding transferable skills alone.5 This has been crucial to the module’s success.

A series of industrial case studies, written in collaboration with industry experts and supported with video clips, provided a framework for study. The module itself is delivered by a series of workshops that introduce the key topic areas, such as teamwork, project planning and marketing. Workshops on intellectual property and scale up/regulatory affairs were delivered by a patent attorney and an industrial chemist, respectively. Bringing in external experts makes a huge difference to the module; the students really engage with the presenters. Mostly, the students appreciate the real-world experience that these individuals bring to the sessions. A number of the external experts are alumni and are very willing and enthusiastic to be involved.

A number of thematic short videos covering intellectual property, project management, sales, ethics and sustainability support the workshops. These videos have the additional benefit of demonstrating some of the possible career routes for chemists. In a feedback focus group, one student commented: ‘I used to think that for a career using chemistry, it was “lab or nothing” but this module has shown us loads of other options.’

Learning output

On completing the module, students should have a better idea what is involved in developing a new product for commercial release in the chemical and allied industries. They should be able to identify the key factors in this process; follow a project management protocol; undertake feasibility studies and market analysis; consider the significance of regulatory compliance or health and safety issues relating to the product or production process; and present their findings to an expert audience. They should also gain some experience of the financial and budgeting requirements of such a project.

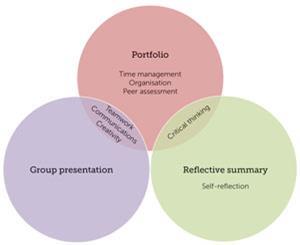

As well as developing knowledge, the course is designed to build skills, including teamworking, communication and presentation, time management and organisation, critical thinking, creativity and enterprise, self-reflection and peer assessment.

Because of the module’s structure and emphasis on skills-based learning, an examination is an inappropriate method of assessment. Instead, students are assessed on a short group pitch presentation, a group portfolio and an individual reflective summary.

The main aim of the group pitch is to help students practice their presentation skills, but using an unfamiliar format. Rather than giving an account of the work they have done, they need to focus on persuading an expert (business and academic) audience of their idea’s merits. This ensures that they also develop the ability to defend an argument, backed up by evidence. They also have to work as a group, so that the presentation is coherent. They need to be concise and avoid duplication, while covering all aspects of the project.

The portfolio provides evidence of all of the work the students carry out over the course of the semester. It includes all the research, plus minutes from meetings (students have identified minute taking as a very useful new skill). The portfolio is assessed for completeness, and is combined with peer evaluation to apportion individuals’ contribution to the group effort. Students have identified this peer evaluation exercise as an important aspect of the assessment, to ensure that marks are allocated appropriately.

The reflective log gives the students the opportunity to focus on what they have learned from the module, and especially the skills that they have developed. Students are asked at the start of the course to assess their aptitude in various skills, as a baseline for their end of module reflections. They are also encouraged to keep a weekly reflective log, although this is not monitored. The majority of students give very honest accounts of their experience, particularly in terms of the skills they have developed and their attitudes towards their future careers.

Evaluation

Feedback after the first cycle of teaching the module has shown that some students struggle with the open-ended nature of the module, whereas others enjoy the opportunity to work independently and stretch themselves. The method of delivery has a much greater impact than the subject matter on the overall student experience of the module.

Achieving a balance between enjoyment and benefit is an aspect that needs further consideration: how can pedagogy ensure enough support so that a module is an enjoyable experience, but maintains a sufficient level of student autonomy so that students obtain maximum benefit, in terms of developing their skills?

It is fair to say that no single learning approach suits everyone. Student opinions are very polarised between those who love the experience of the new approach and the opportunity to work autonomously, and those who are uncomfortable and lack confidence in executing the project, largely due to its open-ended nature.

According to complexity thinking,6 students learn best when they are organised into groups with a diverse range of viewpoints, but with each group having a similar goal. Good relationships between the students (and with the tutor) allow ideas to be proposed and evaluated more freely, and devolving authority from the tutor means that good student ideas are acknowledged and valued. A well-articulated set of ground rules also helps groups function more effectively.

While this module could be considered to be effective in several of these factors, there is definite room for improvement. Perhaps more could be done in the early sessions to establish the ground rules and operating framework. There was also limited diversity in the teams; the module would benefit from including students from other disciplines to bring in different skills and perspectives.

Equally, this method of teaching does not suit all tutors either. The module team has previous experience of working in industry and/or owning spin-out companies, so are on familiar territory with respect to business insight.

It will be interesting to track the graduate prospects of those students who participated in the module, and whether they think, in hindsight, the experience made a difference to their career readiness.

The student perspective

Kristina Paraschiv has just completed her second year of a chemistry degree at Leeds, including the Chemistry: Idea to Market module.

‘I chose the course because I recognised my lack of knowledge outside of the labs,’ she says. ‘I wanted to know more about the business side of a chemistry project, as well as the more practical side of how to put together the necessary materials and pitch it.’

Kristina is currently undertaking a summer research project at Leeds with Andy Wilson’s group, synthesising stapled peptides (protein fragments that are chemically modified to stabilise their folded structures) and looking at their potential as drug leads in disruption of protein-protein interactions. This placement is building up her experience of the way laboratories function and the processes of research, she says. ‘But the idea to market module helped me understand a chunk of the business side to things. It really put my chemistry degree in perspective.’

The current economic climate has made students like Kristina more acutely aware of the skills they need to get jobs when they graduate. ‘It’s a competitive job market out there,’ she says. ‘The course really sharpened my presentation skills. And the insight into the way company projects work has given me a more well-rounded point of view.’

Doing the course has also broadened her view of possible careers using her chemistry degree. ‘It allowed me to understand that, as long as I apply my knowledge, I would be happy working on anything from organic synthesis to water filtration systems,’ she says.

Conclusions

Overall, this approach to developing business skills in chemistry can be considered a success. The level of understanding and awareness of how chemistry-related businesses operate, and awareness among the student cohort of the skills and attributes that are required to be successful has increased, based on their reflective summaries.

The resources are freely available on the RSC’s Learn Chemistry website.7

Samantha Pugh, Stephen Maw, Patrick McGowan and Christopher Pask are engaged in teaching and research at the University of Leeds, UK

References

- K Parker and C Pulham, Business skills resource developer case study, 2012

- C J Garratt and B J H Mattinson, Education, industry and technology (D J Waddington ed.). Pergamon Press, 1987

- S T Belt et al, Chem. Educ. Res. Pract, 2005, 6, 166 (DOI: 10.1039/b5rp90007g)

- S Hanson and T Overton, Skills required by new chemistry graduates and their development in degree programmes. Higher Education Academy, 2010

- G Mason et al, Employability skills initiatives in Higher Education: what effects do they have on graduate labour market outcomes? National Institute of Economic and Social Research, 2006

- B Davis and D Sumara, Complexity and education: inquiries into learning, teaching and research. Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc, 2006

- Learn Chemistry

No comments yet