Meteorites can be bought cheaply online and offer an excellent laboratory teaching tool, explain Luis Lahuerta Zamora, Salvador Lahuerta Zamora and Ana Mellado Romero

Thousands of fragments of rock or metal known as meteorites fall to Earth from space each year. Most of these are tiny, ranging from a few millimetres to a few centimetres in diameter, but very occasionally they are significantly larger. The largest meteorite known to have struck the Earth was over 2000 million years ago at the Vredefort Dome, approximately 120 km from Johannesburg in South Africa. The crater is 300 km wide, and it is thought that the meteorite that created this must have been 10 km wide. Today, the Vredefort Dome is a UNESCO world heritage site.

It is thought that over 99% of all the meteorites found on Earth are fragments of asteroids that originally resided in orbit between Mars and Jupiter. When these fragments leave this region of space, known as the asteroid belt, and travel though outer space they are coined meteoroids. Any meteoroids captured by the Earth’s gravitational force, are sucked in to its atmosphere. Here they decelerate rapidly, causing them to heat up and start to glow (at which point they are renamed meteors or falling stars). Most of the original fragment burns up as it falls, any material that does hit the Earth is called a meteorite.

Meteorite fingerprints

Meteorites originating from asteroid fragments are generally classified into three broad categories – metallic, rocky and intermediate – depending on the proportion of metallic and rocky minerals they contain.

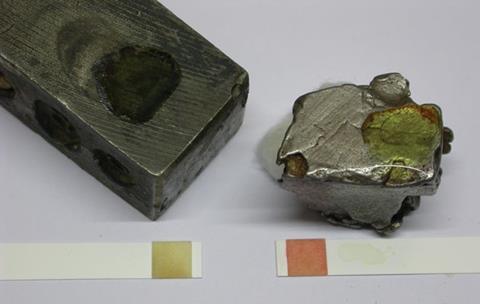

When a metallic meteorite is first discovered, it is often not immediately apparent that it is indeed a meteorite and not simply an archaeological remain of a manmade object. A visual inspection of the specimen is the first step to identification: looking for evidence, such as a melted crust or regmaglypts (indentations on the surface that look like fingerprints), that the object was subjected to extreme heating while crossing the atmosphere. This can be followed by thorough chemical and structural analysis.

Measuring the specimen’s specific gravity is an often-used, simple and economic method for detecting meteorites. This involves weighing the specimen and dividing its mass (in grams) into its volume (in millilitres), which is estimated by the volume it displaces when immersed in water. The mass to volume ratio obtained is the density of the specimen, which will be close to 8 g cm-3 for meteorites. This method, however, is not infallible because some manmade pieces of iron are very similar in density to meteorites.

More conclusive evidence can be found by analysing the specimen’s metallic make-up. Metallic meteorites contain Fe–Ni alloys similar in composition to the Earth’s core, where iron is the major element by far. However, the relatively high content of nickel (ranging from 5 to 35%) in metallic meteorites is one of the chemical indicators that allow them to be discriminated from other manmade iron samples – these usually contain much less than 1% nickel.

The experiment

We have devised a simple, inexpensive and eye-catching experiment that students can do to distinguish between a metallic meteorite specimen and a manmade metallic object, based on its nickel content. This method is based on the classic reaction of nickel(II) ions with dimethylglyoxime. In an alkaline ammonia medium, dimethylglyoxime forms a brilliant red complex with nickel(ii) ions.

Small meteorite specimens (about 5 g) can be purchased for around £6, and each specimen can be reused many times. Using cheap, readily available reagents and the human eye as the detector, this experiment gives results on par with those of the commercial method used as a reference.

As a laboratory exercise with students working in pairs, we estimate this would take approximately 90 minutes. Alternatively a teacher demonstration would only take 15 minutes.

Kit

We strived to cut costs as far as possible by using economical, commercially available reagents. The exceptions to this were the meteorite and dimethylglyoxime.

- A meteorite specimen (we purchased ours from the Spanish firm LITOS. It was certified to come from the Campo de Cielo meteorite that landed in Argentina approximately 4000 years ago)

- Steel carpenter’s hammer (ensure it contains virtually no nickel)

- 8–10 M hydrochloric acid (sold as a descaler and sink and plug hole unblocker)

- 3% hydrogen peroxide (sold as an antiseptic solution)

- Citric acid from lemon juice

- Cotton buds

- Ammonia (sold as a household cleaning product)

- Ethanol (sold as antiseptic alcohol)

- Dimethylglyoxime

The only solution we needed to prepare in the laboratory was the 1% dimethylglyoxime. This was done by dissolving 1 g of reagent in 100 cm3 ethanol. Everything else was used as bought.

The demonstration

The experiment should be simultaneously performed on both samples: the meteorite and the hammer head. Both of which should be placed with the surfaces that are being treated as flat as possible to prevent the reagents from slipping off. The experiments should be carried out wearing gloves and safety goggles, and in a well ventilated space such as a fume cupboard.

First, a drop of hydrochloric acid should be put onto each sample to dissolve the iron and/or nickel in it and any visible changes observed recorded. After two minutes, a drop of 3% hydrogen peroxide should be added over the previous drop in order to oxidise Fe2+ to Fe3+ and any visible changes recorded. Then, a drop of lemon juice (containing citric acid) should be put over the previous two drops and again any visible changes recorded. Next, a cotton bud should be used to absorb the final solution on each sample. Finally, a drop of ammonia and one of the ethanol solution of dimethylglyoxime should be added to each bud, the colour acquired by the cotton recorded.

Questions for the students

-

While carrying out, or watching, this experiment the students should be asked the following questions:

- What chemical reactions are taking place after each reagent is added, and to explain any visible changes observed?

- Why is it necessary to oxidise Fe2+ to Fe3+?

- How can Fe3+ interfere and why is its effect avoided by adding lemon juice?

- What colours do the two cotton buds take and why?

Background

Dimethylglyoxime is a widely used reagent for detecting nickel(II) ions. Its use was first reported by the Russian chemist Lev Aleksandrovich Chugaev in 1905. Since then, dimethylglyoxime has been used as a chelating agent for the qualitative and quantitative determination of nickel(II) ions, with which, in an alkaline ammonia medium, dimethylglyoxime forms a brilliant red complex.

Adding acid to the samples in the first step of the experiment dissolves the Fe–Ni alloy in the meteorite producing the respective divalent cations and hydrogen gas:

Fe + 2H+ → Fe2+ + H2

Ni + 2H+ → Ni2+ + H2

The iron in the hammer will also react with acid to form iron(II) ions and hydrogen gas, and therefore the students will be able to observe tiny bubbles of hydrogen gas on the surface of both samples. This is the only visible change to the samples that the students should observe during the experiment.

As Fe2+ (and many other metal ions) forms a reddish coloured complex with dimethylglyoxime, it must be removed. If it isn’t, its colour would mask that of the nickel-dimethylglyoxime complex the students should be seeing at the end of the experiment.

The Fe2+ is therefore oxidised to Fe3+ by adding hydrogen peroxide (the acid is already present from the first step):

2Fe2+ + H2O2 + 2H+ → 2Fe3+ + 2H2O

However, Fe3+ can also interfere with the detection of Ni2+ using dimethylglyoxime because it precipitates as a gelatinous, reddish brown iron hydroxide [Fe(OH)3] in an alkaline ammonia medium:

Fe3+ + 3OH– → Fe(OH)3

To avoid this issue, citrate ions in the form of citric acid (H3C6H5O7) are added. This forms a water-soluble, virtually colourless complex with Fe3+:

Fe3+ + HC6H5O72– → Fe(HC6H5O7)+

After the addition of the ammonia and dimethylglyoxime to the cotton buds, a marked difference in colour between the two will be observed. The bud containing the solution from the hammer will be yellowish brown, owing to the tiny amount of the iron hydroxide that will inevitably still form. The bud from the meteorite will turn pinkish, owing to the red nickel-dimethylglyoxime complex that has formed. It’s worth noting that this experiment only tells you whether or not nickel is present, full quantitative results require spectroscopic techniques.

This method was validated by comparing the results with those obtained using commercially-available tests strips. These strips, sold by Merck as the MQuant Nickel Test, work in the same way as our experiment, and the colour outcome was identical to that of our method.

Luis Lahuerta Zamora is an analytical chemistry professor at CEU Cardenal Herrera University, Spain. Salvador Lahuerta Zamora is the director of the Minor Planet Center’s Manises Observatory, Spain. Ana Mellado Romero is a chemistry professor at the Polytechnic University of Valencia, Spain

Further information

- The Meteoritical Society

- NASA resources http://1.usa.gov/1zaEV7d and http://1.usa.gov/15I3wWz

- National History Museum resources http://bit.ly/15O1HY3 and http://bit.ly/1LgOFmL

No comments yet