Chemical industry legislation may be the ideal basis for the development of green educational programmes, which teach students about the importance of chemistry in environmental topics.

Over the last three decades environmental issues have been brought to the foreground of our everyday lives. Concerns over differences between northern- and southern-hemisphere countries, as well as the rise of globalisation and international migration, require a new look at how green legislative processes are developed at an international level.

Nowadays, the degree of attention paid to environmental issues is significant. The phrase 'sustainable development' has become synonymous with institutions - be they local or international, business or government - who are willing to integrate economics with environmental issues, without making the latter solely an obstacle for the former.

Sustainability and the curriculum

Schools must get involved too: there is a growing need for environmental topics to be a bigger part of education.1 Sustainability issues pose challenges that need to be become part of the chemistry curriculum, connecting chemistry learning to the broader goals of education, especially ethical topics.2 Chemistry teaching in secondary schools can focus on the interplay of science, technology and society with local issues, public policy making and global factors.

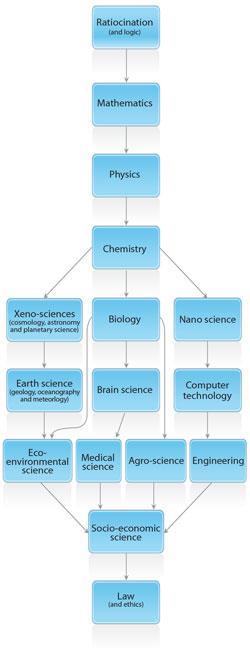

This interaction between chemistry and other subjects is of huge significance. Balaban and Klein have proposed a partial ordering of sciences,3 in which chemistry may be argued as being the 'central science', but the relationship between chemistry and law, economics and ethics is a distant one. Such a relationship should play a larger role in education, so that the central role of chemistry in society can become clearer. Sustainable development is not simply the product of economic, environmental and social factors. The intercultural dimension - the fourth pillar of sustainable development - is becoming more and more relevant in today's globalised society.4 Adding information to the syllabus from some of the legislation surrounding the production, handling and storage of chemicals could be a way to address these needs.

Chemical legislation

It wasn't long ago that a chemical substance could be classified as 'toxic' in the US, 'noxious' in the EU and 'not dangerous' in China. To address this disparity, the Global Harmonization System (GHS) pushed for common labelling throughout the world at the 2002 World Summit in Johannesburg.

Additionally, a ruling on the Registration, Evaluation and Authorisation of Chemicals (REACH), in place in the EU since 2007, has the goal of protecting the environment and human health. Its regulations are based on the assumption that a private company itself - not the ruling government - is best placed to certify the chemicals it produces and sells. All chemicals must be trademarked and analysed by the manufacturer, who must inform the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) of the chemical properties and the safety procedures.

The Classification, Labelling and Packaging (CLP) regulations are Europe's answer to GHS, and have been around since 2009. CLP allows the distinction between different dangerous chemicals, and information about any hazards is provided in safety data sheets (SDSs). CLP regulation is respectful of the GHS criteria and it affects REACH at the same time: in fact, the SDS defined in the CLP are part of the communication protocol as explained in the REACH. The GHS itself leads to new amendments in the REACH regulations, from which some provisions are also to be transferred, such as the obligation for a firm to classify its own chemicals. So GHS, REACH and CLP have a relationship that is not as strictly hierarchical as their date of invention would let us believe. In fact REACH and CLP both have significant feedbacks into previous regulations.

The Italian legislative decree 81/2008 is best known as TUSL (Testo Unico in materia di Salute e Sicurezza nei luoghi di Lavoro). This is of particular interest because of the strict relationship between REACH and TUSL chapter 9 (related to the dangerous chemicals), chapter 10 (concerning the exposure to microbial agents) and chapter 11 (related to treating explosive substances).

Adopting green policies

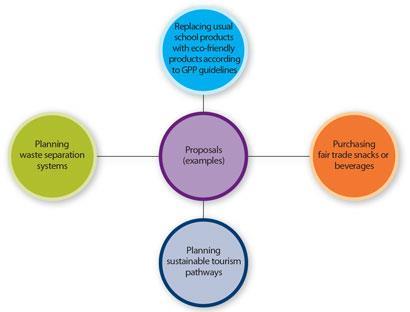

Teaching sustainability in schools is more effective if the institution itself adopts green policies. In particular, a green procurement policy (GPP) represents valuable teaching support and an effective environmental policy tool for schools.5 Since schools are usually not accustomed to green procurement, a GPP could be achieved in steps, starting small and increasing with time. All management policies should be strictly related to the teaching of environmental education, and should consider chemistry as a subject that cannot be omitted.

GPP is inherently connected to Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) - a technique for assessing the environmental impact associated with the stages of a product's life, from cradle to grave. The two concepts can be linked through environmental aspects, through economics and legislature, social issues and the intercultural aspects of sustainable development.

Jargon buster

There are many acronyms in environmental legislation. The following topics are important in defining how economics, politics and law all interact with chemistry.

- Global Harmonization System (GHS)

- Registration, Evaluation and Authorisation of Chemicals (REACH)

- Classification, Labelling and Packaging (CLP)

- National system for safety and health workers protection, for example TUSL (Testo Unico in materia di Salute e Sicurezza nei luoghi di Lavoro) for Italian schools.

- Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

- Green Public Procurement (GPP)

Agenda 21

As a result of the Rio de Janeiro Summit in 1992, Agenda 21 was created to work out a broad programme of action for the 21st century. It aims to balance development with the protection of the environment within the framework of responsible economy.

Local Agenda 21 comprises guidelines for the promotion of sustainable urban development and active citizenship at a local level, by including the subjects directly involved in any decision-making processes.

Indeed, Local Agenda 21 can be used as the starting point for developing a chemistry teaching programme, highlighting the efforts of the chemical community to protect health and environment, as well as the interdependence of scientific, legislative and economic themes. Once such a teaching programme is up and running it should be possible to explain the relationship between REACH, CLP and ethics. This path could be developed in several steps in order to build up a syllabus that fits the local situation.

At the end of this course, suggesting the implementation of a school management plan can be a useful exercise, where students digest, understand and improve the environmental policy of their own school.

This way of working could be adopted by every science teacher, depending on specific educational needs. Chemistry can play a large part in the development of students, ensuring they are aware of the local-global exchange mechanisms and their own ability to affect local policy.

Teresa Celestino is a chemistry teacher and textbook author, currently studying for a PhD in chemical education at the University of Camerino, Italy

References

- M A Fisher, J. Chem. Ed., 2012, 89, 179 (DOI: 10.1021/ed2007923)

- F Dondi, La Chimica e l'Industria, 2009, 9, 100

- A T Balaban and D J Klein, Scientometrics, 2006, 69, 615 (DOI: 10.1007/s11192-006-0173-2)

- E Elamé, Proceedings of the Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie ((Développement durable: leçons et perspectives, Université de Ouagadougou, 4-6/06/2004), 2004, 1, 71

- T Celestino, Il Chimico Italiano, 2011, 1, 13

No comments yet