From early smog problems to modern concerns about air pollution, catalysts pave the way in controlling the emissions from combustion engines

- Although the problem grew, it took many years to legislate against air pollution

- Modern legislation forces increasing challenges for catalyst design

Smog problem

As early as the 1940s and 50s, air quality in many of the major cities in the world had deteriorated to such an extent that a solution needed to be found. A major contributor to this pollution was photochemical smog and low-level ozone caused by the pollutants emitted from motor vehicles.

To combat this problem, in the mid-1970s, initially in California, vehicles were fitted with catalytic converters to remove the pollutants and so improve the air quality, despite some early resistance from the automotive industry. Slowly the uptake of the catalytic converter has spread around the world.

More recently the increase in popularity of diesel vehicles, and introduction of legislation to cover a wider range of vehicle types, has led to new problems and further challenges are expected as we look to the future.

Historical air pollution

Air pollution is not a new problem to human civilisation. In fact in Elizabethan times Shakespeare's witches, as well as encouraging Macbeth's killing spree, also commented on the air quality:

fair is foul, and foul is fair: Hover through the fog and filthy air.

Even before that, in 1306, Edward I brought in an air pollution law, banning the burning of certain types of coal in order to improve the air quality, leading to one poor soul who broke the rule being summarily put to death.

More recently, and since the industrial revolution, there have been numerous records of air pollution impinging significantly on the world's population and human health. Of particular note is the 1952 smog episode resulting from coal burning that killed roughly 4000 Londoners, leading to Parliament enacting the Clean Air Act in 1956, effectively reducing the burning of coal.

Modern air pollution

Today's main sources of worldwide pollution still include power stations burning coal or natural gas. A major concern now is the combustion products from internal combustion engines running on petrol and diesel.

These noxious pollutants include carbon monoxide, unburnt hydrocarbon and particulate matter (PM) from incomplete fuel combustion. Also present are nitrogen oxides, formed in the engine cylinder at high temperature and pressure, and some sulfur oxides, from sulfur found in the fuel and lubricants.

Some of these chemicals are toxic in their own right but in combination can form unsightly, poisonous and deadly photochemical smog, for example through the reactions of nitrogen dioxide with oxygen and hydrocarbons.

Long wait for regulation

The first recognition of the potential need for a catalyst to remove pollutants from gasoline motor vehicles was presented in 1909 when the French chemist Michel Frenkel spoke to the 7th International Congress on Applied Chemistry in London. He proposed 'supplementary combustion in the exhaust box, with the aid of a catalytic agent'.1 This idea was notable as it was only a year after the Model T Ford went into mass production.

However even Frenkel's prophetic insight was preceded by the 1845 Railway Clauses Consolidation Act, the first regulations in the world dealing with transport emissions, in this case smoke emissions from steam engines in England.

Despite these early attempts to bring attention to the effects of transport emissions on air quality, the world waited until 1975 when the US introduced regulations forcing the introduction of catalytic converters onto gasoline vehicles in an attempt to improve air quality and limit the formation of photochemical smog.

Early catalysts

The first devices were relatively simple oxidation catalysts, composed of platinum supported on fine particles of alumina, packaged into a metal canister welded into the exhaust. Their role was to oxidise unburnt hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide using additional air injected into the exhaust gas.

Highly valuable and expensive platinum was chosen for the catalysts after much experimentation with cheaper alternatives. Platinum was more stable in the exhaust gases and less prone to poisoning by sulfur compounds originating from sulfur in the fuel.

Lead poisoning

A major problem encountered in the early days was the poisoning of the catalyst by lead added to the fuel to help the engine run smoothly. It was the need for catalysts on vehicles, as well as concerns over lead's impact on human health, which resulted in the phasing out of lead additives to fuel.

Later, catalysts were coated onto ceramic honeycomb monolith structures (fig 1). These are now usually made of a magnesium aluminium silicate called cordierite (2MgO.5SiO2.2Al2O3). These are themselves inert in the catalytic process and are a huge technological advance from Frenkel's 1909 proposal of mountain flax or cardboard!

By cleaning up the emissions of hydrocarbons, one of the ingredients for photochemical smog was immediately removed from the air. However, most automobiles emitted large amounts of NOx, and this is toxic in itself.

CO oxidation over Pt/Pd:

2CO(g) + O2(g) → 2CO2(g)

Hydrocarbon oxidation over Pt/Pd, eg:

C8H18(g) + 12½O2(g) → 8CO2(g) + 9H2O(g)

NO reduction (CO) over Rh:

2NO(g) + 2CO(g) → N2(g) + 2CO2(g)

Dealing with NOx

The next step was to deal with nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions. Two catalysts were fitted in series:

- A reduction catalyst to remove NOx

- An oxidation catalyst as before.

The engine was calibrated to run rich (excess fuel, to enable the reducing feed for NOx removal). Next, air was added upstream of the oxidation catalyst - a fairly cumbersome approach!

Future advances

The really big technological advance came in the 1980s, where a device was implemented that could combine all the catalyst functions into one catalyst. This was named the three-way catalyst (TWC), and is to this day the mainstay of gasoline vehicle emissions control.

The TWC comprises platinum or palladium to catalyse oxidation reactions, and rhodium for reduction of the NOx, and was made possible due to a number of major technology advances that the automotive industry was able to take advantage of:

- replacement of carburettors by electronic fuel injection systems, allowing more precise mixtures of air/fuel to be maintained

- measurement of oxygen levels in the exhaust using oxygen sensors

- microprocessor control to feed back information from the oxygen sensor (engine running lean/rich) to the injection system.

Efficient combustion

These advances meant it was now possible to run a gasoline engine with the exact stoichiometric mixture of air to fuel for the combustion reaction.

Previously engines had been running either rich (excess fuel, ie reducing conditions) or lean (excess air, ie oxidising conditions). So the engine attempts to run at the perfect ratio at all times, but because control of the air to fuel ratio depends on a feedback loop, small and rapid fluctuations occur either side of the stoichiometric ratio. Therefore, the exhaust cycles between slightly rich and slightly lean.

To enhance the performance of the TWC under these varying conditions cerium oxide is also added. Cerium oxide is easily able to cycle between oxidation states, providing oxygen under slightly rich conditions and promoting reduction when the exhaust is slightly lean.

2CeO2 + CO → Ce2O3 + CO2

Ce2O3 + ½O2 → 2CeO2

Apart from incremental technical advances over the years, to meet ever tightening regulations, this would be almost the end of the story, and much has been written over the past two decades about three-way catalytic converters.3 But recent years have seen increasing concerns over both fuel economy and carbon dioxide emissions, and increasing popularity of more efficient diesel powered vehicles.

Diesel

The German, Rudolf Diesel, invented the diesel engine in the late 19th century but during his lifetime his invention generated little interest. Sadly Diesel's life ended shrouded in mystery and conspiracy theories, when he went missing on a cross-channel sailing to Britain in 1913. However, after much development over the ensuing decades, to overcome the diesel engine's noisy and smoky reputation, today his engine is found in half of the passenger vehicles sold in Europe. They are routinely fitted to ships, trains, buses, trucks and farming or construction machinery.

New challenges

The diesel exhaust composition poses a whole new set of challenges to the chemist and engineer, compared to conventional gasoline powered vehicles. As the combustion occurs in an excess of air (lean), all the emissions control processes must also operate under oxidising conditions.

The rising popularity of diesel vehicles has also brought with it new legislation. This deals with the same pollutants found in a gasoline exhaust, but now also includes PM, which is a major concern. This is typically composed of hydrocarbons and sulfur oxides adsorbed onto solid carbonaceous matter.

Catalysts for diesel

As was the case for gasoline vehicles, emissions control catalysis for diesel is not new. The simplest device to incorporate on a diesel vehicle is a diesel oxidation catalyst, which is based on a supported platinum or palladium catalyst. This uses the excess air from the engine to oxidise carbon monoxide and hydrocarbons to carbon dioxide and water. The first such devices were fitted to fork lift trucks in the 1960s,2 but are now to be found on most diesel powered road vehicles.

Removing the carbon monoxide and hydrocarbons from a diesel exhaust presents a number of challenges, chiefly converting these pollutants often at the low temperature encountered in a diesel exhaust. However, it is the NOx and PM that pose the greatest concerns, both from the point of view of ease of removal and their deleterious impact on human health. It is in the implementation of devices to remove these pollutants where all the major new developments have been made.

Selective catalytic reduction

For NOx control two solutions have been proposed. The first is known as selective catalytic reduction (SCR), in which a reductant, usually a urea solution, is sprayed into the exhaust to provide the conditions necessary for NOx reduction. The urea vapourises and decomposes to ammonia, which then reacts with the NOx over the SCR catalyst, typically supported vanadium oxide (V2O5), or iron or copper supported on zeolite, which is coated onto a monolith (as for the TWC). These reactions occur at temperatures above around 200°C.

In some situations, such as in cold countries during the winter this temperature is difficult to obtain. By installing an oxidation catalyst before the SCR, it is possible to convert some NO to NO2. If the stoichiometry of 1:1 can be achieved, the SCR reaction will occur at a lower temperature, though in reality only a small temperature advantage is possible as urea decomposition starts to become rate limiting below 200?C. Alternatively, using a catalyst that is extruded from the catalyst material, rather than coated onto an inert support structure can also enhance the reaction. These catalyst materials have only become available to the automotive industry in the past few years.

Urea decomposition:

NH2CONH2 → NH3 + HNCO

Hydrolysis:

HNCO + H2O → NH3 + CO2

NO SCR:

4NH3 + 4NO + O2 → 4N2 + 6H2O

NO2 SCR:

8NH3 + 6NO2 → 7N2 + 12H2O

Fast SCR:

2NH3 + NO + NO2 → 2N2 + 3H2O

One of the main problems with SCR is the challenge of injecting the correct amount of urea for the reaction, so that no ammonia exits at the tailpipe. The pungent odour of ammonia in the air is definitely not welcome. A catalyst can be fitted to convert any ammonia breaking through as insurance. It is also necessary to ensure the compliance of the vehicle operator, who now must purchase urea solution solely for environmental purposes.

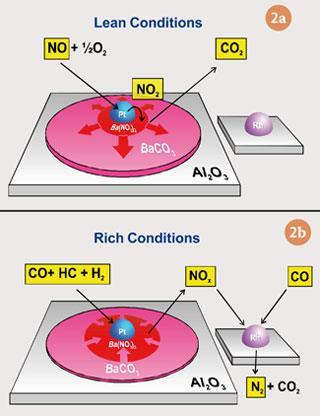

Lean NOx trap

The second NOx control system is known as the lean NOx trap, and this is a more challenging route than SCR. It is likely to dominate for small diesel vehicles, such as passenger cars, at least in the near term, as it is a more cost effective solution for these vehicles than SCR.

In a NOx trap, a NOx storage component, usually an alkali or alkaline earth metal oxide, eg barium oxide, is added to the platinum and rhodium catalyst. Under normal lean diesel conditions this stores NOx as nitrate, but every 60-120 seconds or so the nitrate regenerates by running the engine with more fuel for a few seconds, so that some carbon monoxide and hydrocarbon can reduce the nitrate to harmless nitrogen.

Lean operation(fig 2a)

NO oxidation:

2NO(g) + O2(g) → 2NO2

Storage of NO2 as nitrate:

MO + 2NO2 + ½O2 → M(NO3)2

Regeneration(fig 2b)

Nitrate reduction by CO (or by H2):

M(NO3)2 + 3CO → MO + 2NO + 3CO2

NO reduction (CO):

2NO(g) + 2CO(g) → 2CO2(g) + N2(g)

NO reduction (H2):

2NO(g) + 2H2(g) ⇋ N2(g) + 2H2O(g)

Engine design

This requires complex engine design and operation, and also results in a fuel being used for exhaust clean up rather than motive power, so some of the advantage of using a diesel engine is lost. The technology also relies on very low sulfur fuel, as sulfur can be stored as sulfate on the storage material. As this is very stable, there is a loss of catalyst performance necessitating a periodic high temperature desulfation step. This removes the sulfur once a certain level has been accumulated, thus regenerating the catalyst.

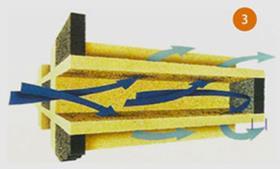

Continuously regenerating trap

For controlling PM one of the most successful devices has been a filter system known as the continuously regenerating trap (CRT®), which has now been fitted to 100 000s of vehicles. This comprises a diesel oxidation catalyst to remove carbon monoxide and hydrocarbons, and also to oxidise some of the NO to NO2. It has already been shown that this can be beneficial for the SCR catalyst, and this is also the case here. In this device, the NO2 reacts with PM trapped on the second component, a diesel particulate filter (DPF) at a temperature of above 200°C. This is known as passive regeneration and is a continuous process.

Typically constructed from cordierite, silicon carbide (SiC), or aluminium titanate (Al2TiO5), these devices capture the PM in their porous wall structure as the gas is forced through the wall from the inlet channel to outlet channel (fig 3).

Even greater passive regeneration performance can be achieved by adding a platinum catalyst to the filter; this is the CCRT® (Catalyzed CRT) device. In some cases it is not possible to use passive regeneration.

Another way to regenerate a DPF is to raise the temperature of the system periodically to around 500°C, so that oxygen in the exhaust can be used for PM oxidation. Heat is provided by injecting extra fuel. This is oxidised on the catalyst generating an exotherm which in turn heats the filter. In this case it is important that the regeneration management is carefully set up, since again this extra fuel partly negates the advantage of a diesel engine. If the temperature is not well controlled and is pushed up too high the result could be melting, cracking or destruction of the filter, at a monetary cost to the owner.

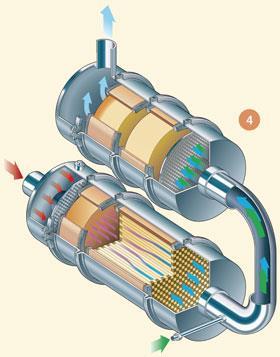

State of the art research

For removal of NOx and PM, the two systems are combined, for example a CRT followed by an SCR catalyst, and this is the basis of the SCRT® system (fig4).

Instead of putting the catalysts in series, it is also possible to incorporate the NOx control catalyst onto the filter itself. This is the focus of the latest, state of the art, research, with SCR or LNT catalysts being coated onto the filter, allowing NOx and PM pollutants to be removed on one catalyst device. A system can be now be designed which saves valuable space on the vehicle, and potentially also cost. These are known as four-way catalysts.

Another idea recently proposed is to layer the catalysts one on top of the other. For example, layering a NOx trap/SCR system, giving a catalyst with wider functionality, but this research is still in its infancy.

Looking forward

Now into the second decade of the 21st century, and over a hundred years after Frenkel's presentation in London, many challenges remain or can be foreseen. Vehicle and engine manufacturers are faced with the challenge of simultaneously improving efficiency and pollutant emissions, and so engine technology will continue to advance at speed. This will eventually lead to an engine that can combine the advantages of gasoline and diesel engines.

Engines will get smaller, operating in new vehicle designs that include a fuel cell or batteries for a second source of motive power.

The future will bring a much wider range of fuel types, such as synthetic fuels and biofuels derived from crops or alternative fossil fuels, ie coal or natural gas, as well as hydrogen, natural gas as a fuel, and blended fuels. Sulfur levels will continue to be reduced, as demanded by legislation, the public and the catalyst industry. It will also be necessary to design catalysts that can operate at lower temperature, a perennial challenge, so that pollutants can be removed even when the exhaust gases are cold, such as just after the engine has been started.

As road emissions continue to improve, the focus will move to other sources of pollutants such as ships and, the ultimate challenge, aeroplanes. Legislation will continue to tighten, and include new regulations, for example, on nitrous oxide, which is a strong greenhouse gas 300 times more effective than carbon dioxide, and also the number of particulates emitted from the exhaust. In fact, the latter is now included in the latest legislation which will come into force in 2014 (Euro 6 legislation). The United States Environmental Protection Agency is now proposing specific N2O regulations also for implementation from 2014.

To address these challenges chemists and engineers are required more than ever before to advance the emissions control technologies already available, and to invent new ways of defeating the problem of motor vehicle pollution.

Andrew works in the Emissions Control Research Group at the Johnson Matthey Technology Centre in Reading, and is also a visiting Research Fellow at the University of Cambridge.

References

- M Frenkel, J. Soc. Chem. Ind., London, 1910, 28, 692 (DOI: 10.1002/jctb.5000281304 - This link will open in a new window)

- J G Cohn, Environ. Health Perspect., 1975, 10, 159 (DOI: 10.1289/ehp.7510159 - This link will open in a new window)

- M V Twigg, Philos. Trans. R. Soc., A, 2005, 363, 1013 (DOI: 10.1098/rsta.2005.1547 - This link will open in a new window)

No comments yet