'...teachers who wish to use practical work to teach scientific method, will have to find time to allow students to undertake authentic enquiry'

Endpoint: Keith Taber has the last word

Experiments have been a favourite activity of school science for many years. Most pupils like them, and many science teachers feel they are an essential part of learning science. Indeed, at one time, school science was a sequence of 'an experiment to...', as recorded through a carefully structured laboratory report: in terms of Aim, Diagram, Apparatus, Method, Results, Conclusions. However the notion that school science should be organised around a series of 'experiments' has been eroded, and perhaps it is now time to recognise that they have little to offer in modern teaching.

Practical work in science

Often in the vernacular of the classroom, the experiment is seen as synonymous with science practical work, and the critique of experimental work in school science has at least two major components. One concerns the validity of equating practical work with experiments, the other concerns the value of practical work itself. School science practical work, involving acids, high voltages and animals sacrificed in the name of education, has costs. It makes science an expensive curriculum subject, and raises serious safely issues. The justification for investing in these costs is the perceived role of practical work in terms of learning science; in learning about the nature of science; and in motivating pupils.

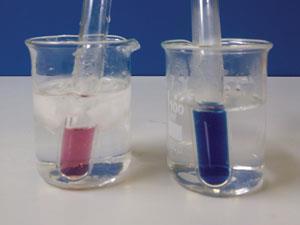

There is limited evidence that practical work actually motivates students, rather than alleviating their boredom with 'theory' by providing a break from listening and writing.1 Students genuinely motivated by science often find learning about the ideas themselves interesting. It has long been recognised that the intended value of school practical work in demonstrating key ideas, and allowing pupils to link theory to actual experience, seldom works.2 Students often misinterpret their observations in terms of their prior conceptions, at least when they are not too busy handling apparatus to observe anything of significance in the first place. If the aim of practical work is to provide opportunities for making observations, and link evidence to scientific ideas, then teacher demonstration offers greater potential for learning. The technician can set up working apparatus, and the teacher can highlight the salient points, and use questioning to ensure the students have appreciated how the phenomenon is understood from the scientific perspective.

Active learning

Science learning should be active, so that pupils are not simply passive observers. This need not mean that so much science curriculum time is committed to students collecting, manipulating, misinterpreting, and then clearing-away materials and apparatus. What is important for learning science is that students' minds, not their hands, are active.3 A scheduled practical lesson could be planned around a demonstration that is proceeded by small groups discussing a relevant concept cartoon designed to elicit preconceptions and predictions of what will happen in the demonstration. Following the demonstration, pupils could be set active learning tasks. A suitable DART (directed activity related to text) could be used to allow students to make quick, accurate notes, whilst leaving time for a more creative writing activity: eg designing and justifying an everyday analogy for the scientific concept. (Dissolving a solute is like paying your money into a bank account because.)4

The processes of science

Now some science teachers will want to retain experiments in their lessons, because they think that it helps teach about the nature of science - 'how science works'. Yet despite so much time being spent doing 'experiments' in UK schools, most students actually have very disappointing ideas about the nature of science. Many school science experiments have been set out as 'demonstrating' or 'proving' some principle, showing they were actually anything but experiments. No wonder so many pupils think science is about having theories (ie guesses or hunches) that are unproblematically converted to facts or laws by doing a simple standard experiment. Even in those sciences where experimental work is the norm, it is nothing like the school science experiment.

So teachers who wish to use practical work to teach scientific method, will have to find time to allow students to undertake authentic enquiry: motivated by genuine questions, where the answers are not given in the class textbook (or even already in the students' notebooks). That will mean working over extended periods to allow students to design, critique and refine experimental approaches. Only then will they get a feel for the experimental method, by doing a real experiment in school science.

Keith S Taber is a senior lecturer in science education at the University of Cambridge.

What do you think?

What are your views on this topic? Let us know by email, Twitter, Facebook or our MyRSC readers group.

Also of interest

Practical Work in Secondary Science: A Minds-On Approach

Ian Abrahams

Related Links

Follow us on Twitter @RSC_EiC

Become a fan of Education in Chemistry on our Facebook page

References

- Abrahams, Practical Work in Secondary Science: A Minds-On Approach. London: Continuum, 2011

- R Driver, The Pupil as Scientist? Milton Keynes: Open University Press, 1983

- R Millar, Int. J. Sci. Educ., 1989, 11, 587

- K S Taber, Enriching School Science for the Gifted Learner. London: Gatsby Science Enhancement Programme, 2007

No comments yet