Show students how lead remains in the capital’s air despite being banned in the last century

Download this

Starter slide, age range 14–16

Use the starter slide with your 14–16 students to give them a new context when studying types of air pollution.

A one-slide summary of this article with questions to use with your 14–16 students: rsc.li/3lvOAWk

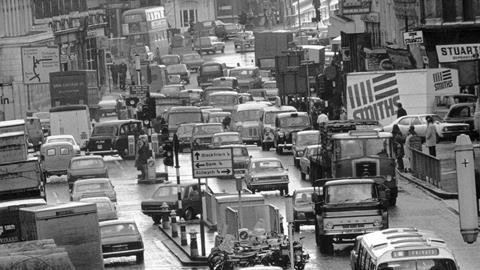

Almost half of the lead polluting London’s air comes from leaded petrol that fuelled cars more than half a century ago, scientists from Imperial College London have found. Although leaded petrol was banned in 1999, the toxic metal has stuck around in the form of lead-laden dust on the UK capital’s streets, kicked up by wind and traffic.

Like many other lead compounds, tetraethyl lead is highly toxic. High lead levels trigger acute poisoning; long-term exposure causes memory loss, neurological problems and a decrease in cognitive function, particularly in children. But this didn’t stop tetraethyl lead from becoming the fuel additive of choice for many decades. Introduced by General Motors in 1921, it was a desperate move after years of searching for a compound that would reduce engine knocking. Tetraethyl lead and the inorganic lead salts that leave cars’ exhausts as a fine aerosol became the main source of environmental lead pollution in the 20th century.

In the UK, lead levels in the air dropped dramatically after the ban. Lead emissions are now below the legal limit, but there’s still around 50 times more lead in the air than the natural background level – a situation study leader Dominik Weiss from Imperial College London likens to passive smoking. No amount is likely to be completely safe.

The lead emitted by cars in the 1960s and 70s has stuck around – in road dust and topsoil. The researchers discovered that more than 40% of the lead found in London’s air today comes from historical leaded petrol. The remaining 60% is likely to come either from brake and tyre abrasion – car components can contain lead as a by-product – or from other non-gasoline historical sources such as coal combustion.

Put this in context

Add context and highlight diverse careers with our short career videos showing how chemistry is making a difference and let your learners be inspired by chemists like Stuart, a project leader in enhanced experimentation, oil & gas.

Comparing metal particles’ isotope ratios with historical data, the researchers spotted the telltale signature of leaded petrol. Lead from petrol is less radiogenic than lead from other sources. While natural lead has a fixed isotope composition for each of the four stable isotopes (204Pb, 206Pb, 207Pb and 208Pb), radiogenic lead is the final product of radioactive decay chains in uranium and thorium ores. Unlike the natural background levels in the UK or lead coming from coal, leaded gasoline used in the UK had low 206Pb/207Pb, and thus high 208Pb/206Pb. This is because lead ore used to make lead additives was from geologically old lead deposits, imported mainly from Australia or Canada.

Read the full story in Chemistry World.

Downloads

EiC starter slide leaded petrol still poisoning London

Presentation | PowerPoint, Size 0.86 mbEiC starter slide leaded petrol still poisoning London

Presentation | PDF, Size 0.24 mb

No comments yet