Nina Notman discovers at how bark beetles are destroying pine trees at an alarming rate

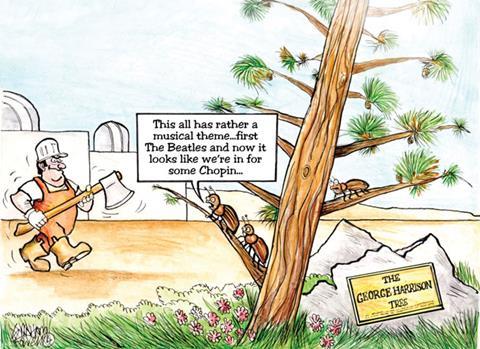

In 2004, a pine tree was planted near the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, US, in memory of George Harrison. As well as being lead guitarist for the UK rock band the Beatles, George – who died in the city in 2001 – was an avid gardener. Over the next 10 years the tree grew from a tiny sapling to around 3 metres tall. But in July this year, LA council officer Tom LaBonge told the LA Times that the tree had died – ironically due to a bark beetle onslaught.

California has been experiencing a severe drought since 2000 and when trees suffer from a prolonged lack of water their ability to fight off pests diminishes. ‘As a result of being drought stressed, the George Harrison memorial tree became infested with a bark beetle which was not positively identified, but based on the species of pine was most likely an Ips species,’ explains LA council tree surgeon Leon Boroditsky.

This pine tree, however, is just one of millions in North America that have succumbed to bark beetle attack over the past 15 years. Bark beetles are natural predators of pine trees, and so the trees have natural defence mechanisms against them. As a beetle bores into the bark, the tree’s first line of defence is to release its resin, which pushes the beetle back.

If the ‘shoving it back out’ approach doesn’t work, pine trees then resort to chemical warfare in an attempt to rid themselves of the pests. In response to beetle attack different species of pine emit higher levels of various volatile organic compounds, including carene, procyanidin and monoterpenes such as α-pinene, β-pinene and β-phellandrene, which repel the beetles.

To counter this, the beetles turn to biological warfare, infecting the trees with fungi, which hinder their ability to produce beetle repelling chemicals.

Infestations of bark beetles are not only bad news for the pine trees, but also for the environment. Trees are responsible for emitting large quantities of volatile organic compounds into the atmosphere where the oxidation products of these compounds can go on to form secondary organic aerosols. These compounds degrade air quality and also have a negative impact on climate. Coniferous trees, such as pines, are estimated to be responsible for approximately 10% of global monoterpene emissions, and preliminary studies suggest that some pine trees release up to 25 times more volatile organic compounds when infested with bark beetles.

The George Harrison memorial tree is due to be replanted soon, meaning that the LA council must be hoping that the line ‘no one I think is in my tree’ from the Beatles’ hit song Strawberry Fields Forever rings true this time.

No comments yet