Fraser Scott explains what this approach could mean for your classroom

All too often, teachers hear, ‘I couldn’t do the question because I didn’t know which equation to use!’ The student may have the procedural knowledge – the ‘how to’ – to answer the question. They may also have the underlying conceptual knowledge – the ‘why’. However, their conditional knowledge is missing – the student does not know the circumstances to use their conceptual or procedural knowledge.

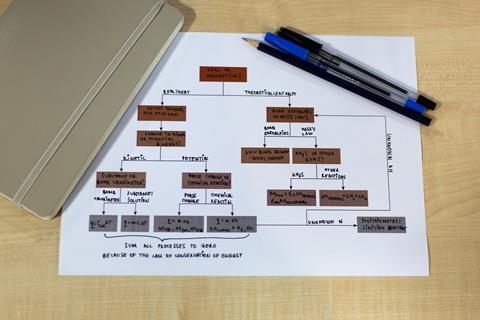

Experts navigate their conditional knowledge like a map when they are solving problems. They often do this tacitly, making it challenging for students to emulate. However, in decision-based learning (DBL), conditional knowledge is attended to in an explicit, rather than implicit, learning activity. Students follow a decision tree, based on experts’ problem-solving strategies, for particular types of problems.

DBL is rooted in cognitive psychology. Students proceed through a problem one decision at a time, so working memory is not overloaded. DBL also helps students internalise knowledge in their long-term memory as it is already arranged in a conceptual framework.

Tough decisions made easy

New research by Rebecca Sansom and colleagues from Brigham Young University, US, investigates DBL within a chemistry context. The researchers asked an expert to complete typical problem-solving questions on heat and enthalpy while thinking out loud. The research team constructed a DBL model for the topic using the conditional knowledge the expert described during the exercise.

They incorporated their DBL model for heat and enthalpy into the teaching programme of around 200 first year undergraduate students studying general chemistry, with a similar number used as a control group. The DBL model was not just used when attempting problems, but was embedded into the conceptual and procedural learning of the topic.

Those students who engaged with the DBL model significantly outperformed the control group on problem-solving questions related to heat and enthalpy. Importantly, 38% of students stated that, in addition to helping them make the correct decisions, the DBL approach helped them understand the problem better. For many students the DBL model helped them to feel less overwhelmed, stressed or confused.

Teaching tips

One of teaching’s great difficulties is attending to the things we do automatically, like using conditional knowledge. It is easy to overlook conditional knowledge during instruction, or to deal with it in an unorganised fashion. It should be straightforward to adopt a DBL approach to help with this. After all, we most likely already do it when modelling our solutions to students. So, why not go a little further and write out this decision framework. The benefits are multiple:

- It makes our preferred problem-solving strategies explicit, and easier for students to engage with.

- Giving students rapid feedback on their problem-solving strategies may take less time if both student and teacher are using a common framework of reference.

- As students become more familiar with the DBL model, it will become automatic, freeing up their working memory to tend to other aspects of a problem.

- DBL can provide a route to promote engagement outside of class. Without it, students may quickly give up on solving problems where they do not have direct teacher intervention.

References

R L Sansom, E Suh and K J Plummer, J. Chem. Educ., 2019, DOI: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.8b00754

No comments yet