Watch the video and download technician notes from the Education in Chemistry website: rsc.li/2PbS7p0

In Ohio in 2006, 15-year-old Calais Weber suffered severe burns to 48% of her body after her teacher poured methanol onto a ‘rainbow flame’ demonstration. Tragically she wasn’t the first student to be injured in this way, and she wouldn’t be the last.

In December 2013 the US Chemical Safety Board (CSB) told Calais’ story in a video highlighting the risks of performing this demonstration incorrectly. Within weeks of the film’s release, another student in Manhattan suffered life-changing injuries in an almost identical accident. This led to calls for the demonstration to be banned and replaced with the dipped-splint method for demonstrating flame colours. These calls were reinforced by the CSB in September that year when another three children and adults were injured in another similar accident in Reno at a science museum.

Coinciding with their calls was yet another methanol fire in Denver. An eyewitness described how ‘the fire extended up to the ceiling and out towards the back wall of the classroom, and all of the students who were hurt were sitting in the back of the room.’ This would still not be the last incident.

Methanol is toxic by inhalation and skin contact, releases heavier-than-air vapours that can travel some distance and has a particularly low flash point. There is no reason to use methanol in the rainbow flame demonstration. Moreover, there’s never a good reason to add a flammable solvent to a demonstration once started – especially from a large bottle. The fire research laboratory of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives released footage of a flame-jetting event, which highlights how easily these demonstrations can go wrong.

Methanol is toxic by inhalation and skin contact, releases heavier-than-air vapours that can travel some distance and has a particularly low flash point. There is no reason to use methanol in the rainbow flame demonstration. Moreover, there’s never a good reason to add a flammable solvent to a demonstration once started – especially from a large bottle. The fire research laboratory of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives released footage of a flame-jetting event (bit.ly/2vHRZqh), which highlights how easily these demonstrations can go wrong. The difficulties eliminating injuries from this demonstration reflect how persistent outdated practices can be.

You can safely perform this demonstration if you pay close attention to the risks (pdf, CLEAPSS members only). Here’s how.

You can safely perform this demonstration if you pay close attention to the risks (bit.ly/2P93grG, pdf, CLEAPSS members only). Here’s how.

Kit

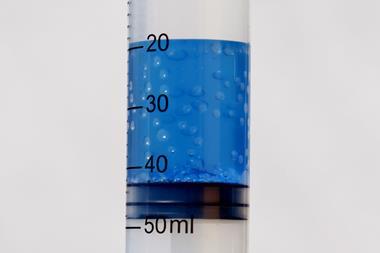

- Approx. 50 cm3 of ethanol (importantly, not IDA/IMS), (highly flammable liquid and vapour, harmful)

- 2.5–3.0 g of the following salts: lithium chloride; sodium chloride; potassium chloride; anhydrous calcium chloride (irritant); hydrated strontium chloride; hydrated barium chloride (harmful, toxic); hydrated copper(II) chloride (harmful, irritant, very toxic to aquatic life). 2.5 – 3.0 g of boric acid (may damage fertility, may damage the unborn child)

- 80 mm borosilicate crystallising dishes or 250 cm3 borosilicate beakers

- Heat-resistant mats

- Wooden splints

- Metre rule

Preparation

Work in a well-ventilated room and wear eye protection. Place the beakers / basins on the heat-resistant mats and spread 2.5–3.0 g of each salt around the base of the container. Dampen the solid with approximately 0.5 cm3 of water and add approximately 6 cm3 ethanol over each. Stopper the ethanol bottle and remove it to at least 2 m away from the demonstration.

In front of the class

Position the audience 3 m away from the demonstration with eye protection. Ask for a volunteer to switch off the lights if the switch is not nearby. Ignite the solvent in each container with a splint on a metre rule. Each beaker will burn with a characteristic colour. Allow the flames to burn out – do not attempt to add more solvent until at least 15 minutes have passed since the last flame extinguished.

Safety and disposal

Boric acid is a teratogen – you may not wish to use it.

Do not be tempted to pour more alcohol onto the flame or hot glassware in order to extend the demonstration. Use only borosilicate glass (avoid watchglasses, which are usually made from soda glass and may crack).

Dilute the contents of the copper(II) chloride beaker to 1 l and pour down the sink. The other salts will be unchanged at the end of the demonstration and can be retrieved and recycled for future demonstrations.

Declan Fleming

Downloads

Technician notes

Word, Size 54.5 kbTechnician notes

PDF, Size 46.06 kb

4 readers' comments