Why stop at asking students to give presentations? The technology to empower them to produce versatile and reusable blended learning objects is readily accessible, explains Simon Lancaster

Requiring students to prepare a highly visual account of a topic using software like PowerPoint, Keynote or Prezi is common practice at every level of education.1 In higher education, presentations not only provide an alternative assessment strategy, balancing the reliance on examinations, but they also offer translatable skills training, which is essential for the modern professional workplace.2 However, there are disadvantages. The presentation is short-lived, all that preparative effort for a brief talk and, unlike an essay or report, it cannot be recalled in full to help with revision or be emailed to someone who was unavoidably detained.

Recently we discussed the potential of lecturers using video in chemistry learning and teaching and introduced the concept of vignettes, short interactive highlights of chemistry screencasts.3 Here we look at handing over the production of vignettes to the students.

Capturing the presentation

There are many web-based and stand-alone solutions that allow the capture of what appears on the presenter’s screen to be synchronised with their narration, a process called screencasting. This is in contrast to ‘total lecture capture’, which implies a camera trained on the presenter to accompany screen and audio feeds. Good live total lecture capture requires planning and excellent facilities, essentially a dedicated production team. In contrast, to screencast you need only a personal computer or tablet and a microphone, facilities in reach, not just for most teachers, but for most students.

We observe that screencasting presents an opportunity for asynchronous viewing of student presentations. In some instances it will be inappropriate on health or welfare grounds to ask a student to give a talk in front of their peers and screencasting presents an acceptable alternative. If it proves logistically impossible to accommodate every speaker in a given timetable slot, this approach presents the teacher with a solution to the scheduling dilemma. More generally this approach can be valuable in building student confidence before presentations to large audiences or providing feedforward before live seminars. Where the learning objectives do not include refining presentation skills, but nevertheless PowerPoint or equivalent is regarded as the best composition medium, screencasting may be the ideal solution.

The scenario

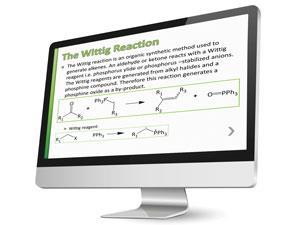

In the school of chemistry at the University of East Anglia, the MChem (integrated masters) final exams have a synoptic component, drawing upon lecture courses delivered in the first and second years of the degree. Rather than having faculty review the material again, colleagues introduced a series of student-led revision seminars. Pairs of students were charged with preparing presentation and revision notes on one of a series of topics from the early part of the degree. This provided both a revision strategy and a platform for practising presentation skills. However, at the point of examination preparation, students were left with a set of notes and a vague recollection of a long past seminar. Meanwhile at UEA we have been screencasting a large proportion of our lectures for a number of years. Working with the University of Southampton we developed interactive blended learning objects, highlighting the take home messages of some of these lectures, which we called vignettes. These are a much better format to support student revision than binge-watching longer screencasts. It was a natural progression to consider students authoring vignettes.

Implementation

Rather than present our students with the daunting prospect of developing a blended learning object from scratch, we scaffolded a stepwise process where they gave a presentation then turned it into a vignette. The students were first paired and allocated a revision topic, such as the stability of organo-transition metal complexes or electronegativity and its role in predicting reactivity. The pairs were chosen arbitrarily, with the intention of simulating a work environment in which one cannot always choose your collaborators. Allowing students to choose their own partners may moderate the challenge, but interestingly this aspect did not attract any comment from our cohorts.

Since the material had already been taught in years one and two of their course, we could ask our students to provide a draft presentation early in the semester before there were any competing deadlines. Two distinct sets of feedforward were then provided by faculty on each draft presentation. Feedforward was a key part to the whole process. Both the presentation and the vignette production were entirely formative exercises with no mark directly attributed. The incentive for students to engage was the belief that they were working together, in pairs on individual topics but as a group to prepare for the final examination. Several stages of constructive feedback were used to maximise the formative potential. The first type of feedforward on the draft presentations was a technical commentary correcting mistakes, ranging from typographical errors to wrongly aligned curly arrows. Secondly, innovative use of screencasting was made to provide feedback running through the presentation, slide by slide and animation by animation, to comment on the general approach and suggest opportunities for interacting with the audience.

Students were then given time to incorporate both sets of suggestions before delivering their presentations. The presentations were recorded using the software package Camtasia Studio.4 Some of our students incorporated the use of electronic audience response systems in their talks. In our experience of presentation peer review, students are reluctant to provide constructive feedback because it can appear pointlessly critical. The beauty of this approach is that students are aware that any improvements they suggest will impact upon the standard of the revision tools available to them later in the course.

Workshops on using Camtasia Studio were provided but were rather under-used, with students choosing to teach themselves. In many cases vignette production was left until after the workshop and immediately before the submission date. We responded by reducing the number of workshops and providing online screencast resources explaining the editing process, all of which are freely available.5

All of the student vignettes were published on the module page of the university’s virtual learning environment (VLE), Blackboard. The nature of the vignette means that although video-only versions can be, with permission, published to sites such as YouTube, the interactive elements need to be hosted as web pages or as SCORM content within a VLE. Where student vignettes were of exemplary technical standard (and with the permission of the students), we have published as open educational resources (OER) accessible to all.6

Blackboard allows usage statistics to be tracked, and through monitoring numbers of views it was seen that the average student accessed each vignette multiple times in the run up to the exam.

Evaluation

The question naturally arises whether these vignettes led to improved examination results. It is very difficult to satisfactorily demonstrate such an effect for a number of reasons: the indirect relationship between the topics and the examination questions, the unreliability of statistics for a student cohort of less than 30 and the inevitably variable quality of the vignettes. Noting those caveats, prior to the introduction of vignettes the average mark for the synoptic questions was 53.44% (SD 13.29) and afterwards 57.27% (SD 18.77). Perhaps slightly more telling is that prior to their introduction only 52% of students achieved the pass mark in the synoptic question, whereas in 2012–2013 this figure increased to 60%.

Students were very positive about screencasts and vignettes

Additionally, qualitative student evaluation was conducted through a student focus group – independently organised by Gurpreet Gill at UEA’s centre for staff and educational development – to gain insight into how the participants viewed the vignette project. None of the faculty involved with the project participated in this evaluation process. Pointedly, the focus group took place before the examination but while many of the students would be beginning to revise. As had been found for years one and two, students were very positive about screencasts and vignettes. However, they were less positive about producing them themselves, largely because of the effort required and the difficulty of mastering the software at the last minute. We believe, however, that the Camtasia Studio interface is very simple and extensive online instruction is available. What we had not anticipated, but with hindsight is not surprising, is that involving students in the design and pedagogy of blended learning objects gave them a better appreciation of the effort that we as a school had invested in providing these resources for them.

Evaluation from student focus group

- Thought about information in a different way when preparing interactive questions

- You can add more to existing presentation which is good

- Made you go over material you might have forgotten

- Had lecture notes and additional material (narration)

- Highlights key areas

- No experience made preparation difficult

- Students don’t have a lot of time to do it. Takes longer than actual PowerPoint

- Need more Camtasia experience/easier software

- Very good revision tool if a lot of effort is put into producing it

- Quality may differ and affect revision – can’t rely on them

Legacy

Our approach has the potential to add value to any activity where students are asked to present their work. The screencasting technology is not restricted to PowerPoint and does not inhibit the use of technologies such as clickers in the student presentations. Asking the student to prepare a vignette produces a lasting legacy from their talk, which can be a reusable teaching aid for that or future generations of students and a tangible digital item for a portfolio of work. Production of the vignette allows students to exercise creative and technical skills not always developed on our degree programmes. A bonus is that producing these learning objects gives the student an insight into teaching and an appreciation of the effort we put into preparing resources for them.

Recommendations from student focus group

- Introduce the approach earlier on in the degree programme, for example during the first year, and supplement this with tutorial questions focused on the vignette topic

- Allow more time for introducing the approach and training students in usage

- Award credits and marks for the vignettes

- Allocate vignettes to individuals rather than pairs, and if feasible base this on subject interests

- Investigate use of other presentational software packages

Simon Lancaster is a senior lecturer in chemistry at the University of East Anglia, UK

Acknowledgements

With thanks to the MChem students at the University of East Anglia and our colleagues in the school of chemistry for their support and cooperation throughout this project. We are grateful to Gurpreet Gill for the independent management of the focus groups. Thanks also to the Individual Teaching Development Grant and National Teaching Fellowship Schemes of the Higher Education Academy for financial support.

References

- J M K McAlpine, Assessment & evaluation in higher education, 1999, 24, 15 (DOI: 10.1080/0260293990240102)

- T L Overton, S Johnson and J Scott, Study and communication skills for the chemical sciences. Oxford University Press, 2011

- Education in Chemistry, July 2012, p13 (http://rsc.li/MOU2YA)

- Camtasia Studio

- Jisc guide to broadcasting on-screen activity

- [link no longer available]

No comments yet