The conservation lessons we can learn from the discovery of one of the oldest known periodic tables

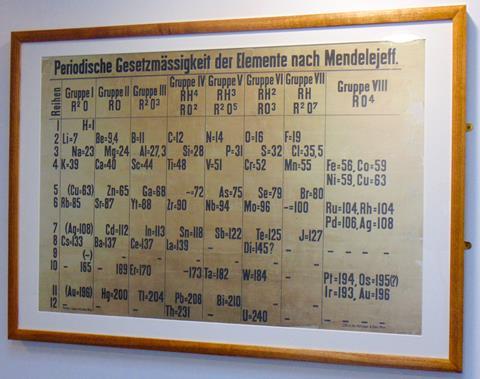

In 2014, chemistry lecturer, Alan Aitken was cleaning out a store at the University of St Andrews. Among many mundane items he found a bunch of rolled-up charts, which included a large but flaking wall chart resembling an embryonic periodic table.

On the chart, some elements were clearly shown, some were blank – yet to be discovered – and a few had been scribbled by hand. For example, both gallium and scandium (discovered in 1875 and 1879 respectively) are shown, while germanium (discovered in 1886) is not. This helped researchers to date this periodic table to between 1879 and 1886. It is thought to be one of the oldest known classroom charts of the periodic table.

The edges of this periodic table were flaking away. Intervention was necessary. Richard Hawkes, a paper conservator from Artworks Conservation, led the process. He explained that ‘the paper had turned a darker brown colour overall, although it would never have been white.’ This suggested photo oxidation from exposure to light, acidity in the paper, and the presence of wood pulp (lignin) in the material.

A world where we rely on written records may seem more and more alien to our students but this article highlights the challenges of preserving our written history. There is much more to the chemistry of paper than we tend to realise and this article weaves familiar chemistry including pH, solubility and polymerisation into an engaging narrative.

Solutions and solubility

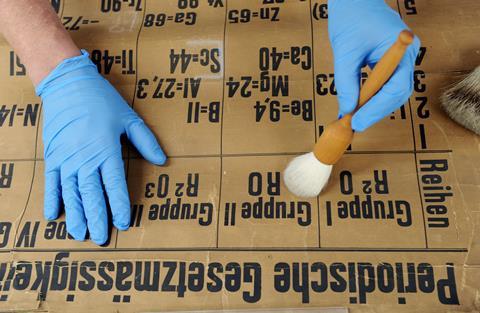

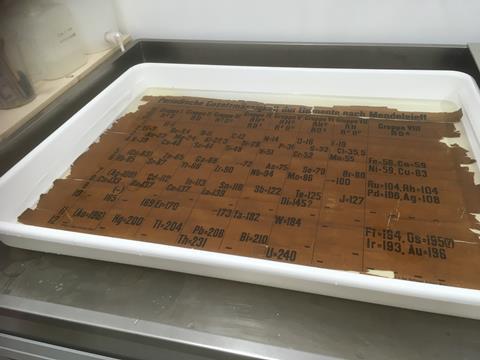

Dirt was ingrained in the surface of the paper and there was also loose dirt and dust on the surface. The canvas backing was carefully removed and the remaining surface was laid in a giant tray of filtered water. Using calcium hydroxide the pH of the water was adjusted to neutral. This process washed away surface layers of dirt and discolouration that were soluble.

Before immersing it, Richard had done careful solubility tests on the ink, using tiny triangles of blotting paper, but he confessed: ‘no amount of testing can prepare you for immersing in water!’

The water was renewed regularly to prevent any ill effects of acidity washed from the paper into the water. The next step was an alkaline wash. The periodic table was immersed in a dilute solution of magnesium hydrogen carbonate, which helps to de-acidify the paper. When it dries, it leaves behind an ‘alkaline reserve’. This insoluble residue is magnesium carbonate, and helps to protect the paper against future acid attack.

Magnesium hydrogen carbonate is not available as a solid. Richard prepared his solution from a 0.1 M solution of magnesium hydroxide (the substance also found in household Milk of Magnesia remedies) by bubbling carbon dioxide from a soda siphon through it, giving a pH of about 6. Carbon dioxide in water produces slightly acidic conditions. This is less risky than working with an alkali at higher pH, which could turn the linseed oil in the ink into soap. After this immersion treatment, the table was dried face down. Drying it face down meant that any tiny gritty carbonate deposits left would be on the back. The pH of paper undergoing such treatment rises from pH 6 to nearer 10 as it dries.

Richard used a cooked wheat starch paste and Japanese kozo paper – a very pure, light, long-life variety of paper – to repair tiny tears. Gelatine filled porous gaps, in a technique called ‘sizing’.

Pulp fiction

The paper used for printing this chart was not high quality. This is true of many historical paper artefacts. Often low grade paper is used for items like a ticket or a poster where its lifetime is expected to be short.

The printing press and demand for mass produced paper transformed late 19th century news and printing with the use of ground wood pulp paper. However, the main constituent in paper, cellulose (a polymer) has shorter chains when derived from wood pulp rather than traditional linen and cotton rags, and it’s less robust. Wood pulp also contains lignin (the structural material in plants), which interferes with the cellulose chains aligning in paper, discolouring the paper and reducing its strength. The de-acidification immersion helps to remake some hydrogen bonds between cellulose fibres during drying.

Fake your own ancient paper

A stand-alone lesson or investigation, age range 11–14

In this activity students use common household acids to carry out acid hydrolysis on paper, faking the ageing process on paper. This can be used as a stand-alone lesson led by the teacher or students can investigate how different factors affect the ageing process either in class or in an enrichment session or science club.

Paper degradation

Light and acid are the two main causes of degradation in paper. Oxidation initiated by light makes paper more brittle and makes it appear more yellow. Acid hydrolysis can break the link between the monomers (glucose units) of cellulose, weakening the fibres. Strongly alkaline conditions are damaging too, so conservators prefer to work between pH 6 and 9. Conditions above pH 10 have been shown to cause damage to the cellulose polymer, and this can cause peeling. Acidity can be present in the paper itself from its manufacture, or in the atmosphere. In polluted urban atmospheres, sulfur dioxide, for example, can be absorbed by paper and slowly converted to sulfuric acid. Another challenge comes from iron gall ink. This was widely used in manuscripts; for example, Beethoven’s manuscripts in the German National Library. Acid and iron can attack paper. Conservators prefer to use calcium rather than magnesium in such conservation cases, as the pH of calcium hydrogen carbonate is within the range where iron gall ink is stable.

And what about the St Andrews periodic table now? It was returned to the University’s Special Collections in 2018 where the climate-controlled stores will help to conserve it for future generations. You can see a full-sized reproduction in the School of Chemistry.

Many thanks to Richard Hawkes for his help with this article.

Article by Morag Easson, a Royal Society of Chemistry trainer and independent science education consultant. Resource by Kristy Turner, a school teacher fellow at Univeristy of Manchester and Bolton School

More resources

11–14

Neutralisation circles is a fun, introductory practical activity using universal indicator. Students can see the pH of areas of the wet paper changing as neutralisation occurs on the paper. The paper can be dried and kept for reference.

14–16

An important part of the paper conservation process in the article focuses on metal hydrogen carbonates, metal carbonates and their reaction with acids, and the use of pH. It gives a different context for applying these core ideas.

- Making magnesium carbonate is a class practical demonstrating the formation of an insoluble salt in water.

- Acid rain in the classroom is a practical activity from SSERC that generates tiny amounts of SO2 and NO2 gases and bubbles them each into water/indicator.

- AfL 46: Word equations provide clear exercises in word equations, grouped in patterns, with examples related to the chemical reactions in this context.

16–18

Equilibria involving carbon dioxide in aqueous solution is an excellent practical activity demonstrating the acidity of fizzy water with indicator, and what happens when this is degassed. Discussions of this equilibria could be extended, eg the blood’s buffering system.

More resources

11-14

Neutralisation circles is a fun, introductory practical activity using universal indicator. Students can see the pH of areas of the wet paper changing as neutralisation occurs on the paper. The paper can be dried and kept for reference: rsc.li/2YinY0w

14-16

An important part of the paper conservation process in the article focuses on metal hydrogen carbonates, metal carbonates and their reaction with acids, and the use of pH. It gives a different context for applying these core ideas.

Making magnesium carbonate: the formation of an insoluble salt in water (by precipitation starting with soluble salts): rsc.li/2YwPfM1

Acid rain in the classroom is a practical activity from SSERC that generates tiny amounts of SO2 and NO2 gases and bubbles them each into water/indicator: bit.ly/2YGRuws

AfL 46: Word equations provides clear exercises in word equations, grouped in patterns, with examples related to the chemical reactions in this context: rsc.li/2MuvOwI

16-18

Equilibria involving carbon dioxide in aqueous solution is an excellent practical activity demonstrating the acidity of fizzy water with indicator, and what happens when this is degassed. Discussions of this equilibria could be extended, eg the blood’s buffering system: rsc.li/2Ovuo88

Downloads

Fake your own ancient paper

Word, Size 0.15 mbFake your own ancient paper

PDF, Size 0.14 mb

No comments yet