As lithium-ion batteries are pushed to their limits, what technology could replace them?

Three weeks after launching its Galaxy Note 7 in August 2016, Samsung started to receive reports of exploding phones. The company replaced the batteries in 2.5 million devices, but by October, following more fires, including one onboard a plane in the US, it halted sales and recalled 19 million phones. The final tally was 92 overheating batteries and 26 reports of burns.

The recall, which Samsung estimates will cost it in excess of $5.4 billion (£4.5 billion), has been laid squarely at the feet of the lithium-ion batteries that power the phones. But lithium-ion batteries catching fire is not a problem unique to Samsung, in fact it has been a concern for decades. Sony estimates that since their launch in 1991, an estimated over 7 million lithium-ion batteries have been recalled in laptops alone. Recent years have also seen reports of exploding hoverboards, e-cigarettes, a battery pack in a Tesla electric car and now smartphones.

Getting to the root cause

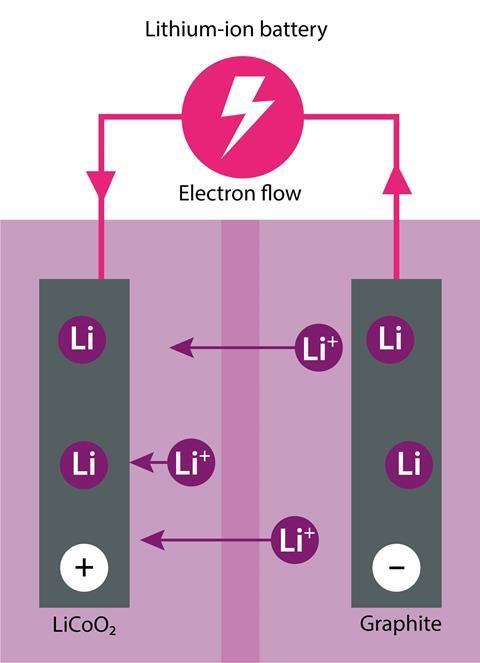

Lithium-ion batteries are made up of a layered oxide cathode (often lithium cobalt oxide, LiCoO2), a graphite anode, an electrolyte (typically lithium hexafluorophosphate, LiPF6) in an organic solvent, and a microporous separator. This separator is a polymer layer, that can be thinner than human hair, which prevents short-circuits between the anode and cathode while at the same time allowing ions to flow between them. When charging, the lithium ions and electrons move through the electrolyte from the cathode to the anode. And during discharge, the ions move back again to the cathode.

The initial trigger of the fires in these batteries is often a short-circuit between the two electrodes, which can occur if there is a fault in the separator. This causes the battery to discharge very rapidly producing a lot of heat and chemical changes that lead to the temperature inside the cell rising even more rapidly. Chemical engineers call this thermal runaway. The highly oxidised cathode can decompose and lose oxygen during this rapid heating. This oxygen, in the presence of a volatile electrolyte, provides the perfect conditions for a battery to ignite.

The short circuits can occur for a number of reasons including due to accidental physical damage to the batteries during use. Another well-known phenomenon that causes short circuits is the formation of dendrites – microscopic lithium needles. These can form if a battery continues to charge past the anode capacity. Bill Macklin, chief engineer at Abingdon-based battery materials company Nexeon, explains this can cause plating of lithium on the anode surface or the formation of needle-like dendritic structures. ‘They are a potential hazard because they can short all the way through back to the cathode by penetrating the separator,’ he says.

In 2006 Sony recalled its batteries worldwide, thanks to microscopic metal or ceramic particles that had been inadvertently embedded in the battery during manufacture. Over time these penetrated the separator and caused a short. ‘During the cutting process, when you cut through the ceramic lithium metal oxide [cathode], some powder can become dislodged from the coating and get embedded between the coating and the separator,’ says Bill. ‘Or you can have metal fragments from when you slice the metal current collectors as you cut the electrodes to the right size.’

Samsung used two different battery suppliers for the Galaxy Note 7, which added to the confusion over the potential cause of the problem. In January, after more than three months of speculation following the recall, Samsung reported the results of its investigations into the fires. The company tested 200,000 devices and 30,000 batteries, finding that the batteries from the two different suppliers had different issues.

Those from one manufacturer were too large for the phones. And being squashed left them prone to damage; specifically the crimping of the electrodes. This in turn weakened the separator causing short circuiting. Those sourced from the second supplier had thin separators, meaning the risk of damage to them was higher. Additionally some manufacturing inconsistencies were identified including some phones missing insulation tape and others having sharp protrusions internally that could damage the separator.

Tweaking the status quo

But safety concerns are not the only reason researchers are scrambling to develop a replacement for lithium-ion batteries. The lithium-ion cell is getting nearer to its theoretical maximum energy density of 600 Wh kg-1, meaning they may not be able to offer the energy storage capacity needed for energy-hungry applications such as electric vehicles. (The energy density is the amount of energy stored in a given system per unit volume or mass.) Lithium-ion technology is still pushing itself further, but as Bill admits it’s ‘evolution not revolution’. David Ainsworth, chief technical officer at Abingdon-based battery developer Oxis Energy, agrees: ‘There has not been much movement in the last five years.’ But progress towards a replacement that can hold more power has been equally slow. ‘People are struggling to come up with something better,’ says Bill, ‘there isn’t really a credible near term replacement’. There are however a number of exciting options further down the pipeline.

One angle being taken by some research groups is to design a superior cathode material such as layered lithium-rich transition metal oxides. Bill’s Nexeon, a spinout from Imperial College London, is working on the anode instead, replacing graphite with silicon. Anodes made of silicon can intercalate (hold in their structure) more lithium – meaning they can hold more charge. The main battery manufacturers are already using low percentages of silicon blended with the graphite, but there is a snag to this approach. ‘If you fully lithiate silicon the expansion is about 280% of the initial volume, whereas with graphite the expansion is about 10%,’ explains Bill. Nexeon’s answer is to grow silicon nanopillars. ‘If you can adopt nanosized features and structures then although the same percentage volume changes occur, the stresses in the materials are sufficiently reduced,’ Bill says.

Another strategy to boosting power capacity is getting rid of the liquid electrolyte. ‘People have been trying to develop solid state batteries for several decades and I think it’s so far proved unsuccessful,’ notes David. The problem has been finding a solid ionic conductor that has high enough room temperature conductivity, but there have been advances here. Electronics giant Dyson recently acquired solid-state battery developer, Sakti3, a spinout from University of Michigan in the US. In 2014, Sakti3 unveiled a solid-state cell with a healthy 400 Wh kg-1 energy density. Superionic conducting materials are the key to this advance. And in 2016, Japanese researchers published several promising new materials of this type, one being Li9.54Si1.74P1.44S11.7Cl0.3.1 The 3D mesh-like structure of this material arranges the lithium ions in channels through which they can hop.

Changing the chemistry

These are all tweaks of the original lithium-ion idea, but the next generation of batteries may come from a different chemistry altogether. David’s Oxis Energy is developing a lithium-sulfur cell that uses a metallic lithium metal anode and a sulfur-based cathode. ’You get a much higher theoretical capacity from sulfur than you do from something like lithium cobalt oxide and that’s due to the electrochemistry,’ explains David.

In a lithium-ion cell, the ions move in and out of the electrodes, but in the lithium-sulfur cell an electrochemical reaction happens in the electrolyte solution. During discharge, sulfur dissolves from the cathode to form longer chain polysulfides which are reduced to shorter chain polysulfides and eventually Li2S itself, with the process reversed during charging. Meanwhile, lithium is dissolved from the anode surface during discharge and plated back onto the anode while charging.

The tantalising theoretical energy density of 2600 Wh kg-1, nearly five times that of current lithium-ion technology, makes the lithium-sulfur battery a serious contender. David suggests that one potential future application for his company’s battery is electric vehicles. ‘I think you can probably envisage at least 50% more range [distance per charge],’ he says. Most current electric cars achieve only 200 miles.

Where lithium-sulfur batteries do fall down is with their size. While sulfur is light for the amount of energy it can store (50% lighter than Li-ion), it has a lower energy density by volume. This means it’s unlikely to be useful for consumer electronics. So far Oxis energy can produce cells of 400 Wh kg-1, which compares well to the best in class lithium ion at around 240 Wh kg-1.

At first glance, returning to highly combustible lithium metal (the first lithium-ion batteries contained this) may seem like a backwards step for safety. ‘We actually make quite a large selling point of the safety credentials of our technology,’ says David. The sulfur acts as a passivation layer if any short circuit occurs and therefore prevents thermal runaway. Charging and discharging also totally dissolves any byproducts, so any dendritic lithium is re-dissolved. ‘People understand theoretically why it is better, because of the chemistry, but until you see a big player actively doing it, then you have got to be slightly worried about having too many bets on lithium-sulfur replacing lithium-ion,’ Bill cautions.

Another alternative chemistry on the horizon is the sodium-ion battery, being developed in the UK by Sheffield-based company Faradion. Last year they received a government innovation grant to develop a prototype battery for electric vehicles. It works on the same principle as the lithium-ion battery but using the larger alkali metal. Critics say these batteries are unlikely to give improved energy densities, due to the sodium ion’s larger size and lower mobility – which would make charging and discharging slow. But Faradion claim with the right cathode and anode this isn’t the case. It also has a big cost advantage, sodium being about 25 times cheaper than lithium.

A lot of hot air?

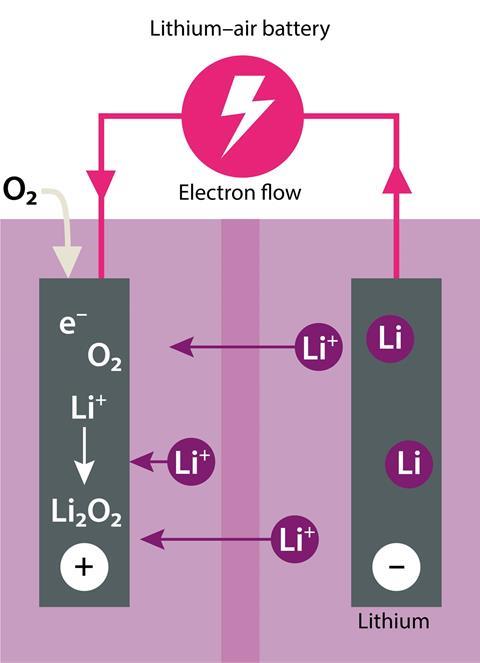

The holy grail of battery technology is the lithium–air battery, with a theoretical energy density of 12,000 Wh kg-1, which compares favourably to that of 13,000 Wh kg-1 for gasoline. The cell consists of a lithium metal anode with oxygen from air introduced at the cathode through a carbon fibre membrane. Peroxide ions form at the cathode and then react with lithium ions to form lithium peroxide (Li2O2), with the electrons transferred providing the electrical energy.

Although the chemistry seems simple, there are some large hurdles to overcome before this technology is ready to hit the shelves. Most attempts so far have shown disappointingly low efficiencies and the battery chemistry can be completely stopped if the anode is ‘poisoned’ by the production of lithium peroxide films which prevent electron flow. The cells also require pure oxygen, as water and carbon dioxide can cause the formation of lithium hydroxide and lithium carbonate, which stops the battery recharging.

The possibility of a commercial lithium–air battery seemed to fade in 2014, when it was reported that both computing giant IBM and the US Joint Center for Energy Storage Research had wound down their lithium–air battery research programmes, but in October 2015 the story seemed to look more hopeful. A paper from the lab of Clare Grey in University of Cambridge, published in Science, claimed to have solved the recharging problems by adding lithium iodide and water to the cell.2 She postulated that as the battery discharged, hydrogen was stripped from the water to form lithium hydroxide (LiOH) crystals rather than Li2O2: negatively charged iodide ions converted into triiodide ions then combined with the LiOH crystals, dissolving them away, and allowing for complete recharging.

Clare claimed her test cells could be charged and recharged more than 2000 times. But in 2016 her results were disputed. Two rebuttals were published in May from researchers at seven universities and national laboratories in the US, China, and Australia. They argued the findings were not as result of a lithium–air cell, but rather a lithium–iodine battery, another high-energy rechargeable battery, but without the potential of lithium–air technology.3,4 Whether there is a future for the lithium–air battery remains to be seen. ‘I think there is a solution, but we could be talking 20 years plus for a practical air cell,’ says David.

The search for the best battery design – in terms of safety and capacity – continues, with developments in lithium-ion cells and alternative technologies. But as our demand for more power grows in both the mobile device arena and electric vehicles, it may be that we see more of the type of problems experienced by some Samsung Galaxy Note 7 users. ‘People are close to the margins of what is practical to build now,’ says Bill ‘and that’s when safety risks can increase’. But finding new, safer battery chemistries with good energy capacity ‘is going to be a long hard road’, he concludes.

Rachel Brazil is a science writer based in London, UK

References

1 Y Kato et al, Nat. Energy, 2016, article number: 16030 (DOI:10.1038/nenergy.2016.30)

2 T Liu et al, Science, 2015, 350, 530 (DOI: 10.1126/science.aac7730)

3 V Viswanathan et al, Science, 2016, 352, 667 (DOI: 10.1126/science.aad8689)

4 Y Shen et al, Science, 2016, 352, 667 (DOI: 10.1126/science.aaf1399)

1 Reader's comment