Simon Rees reveals the origins of some chemical terms and what they can mean for students

On a cold, damp evening during the Christmas season of 1860, an expectant crowd gathers in the gas-lit gloom outside the Royal Institution in London. They shuffle into the steep banked seating of the auditorium and an excited hush descends as Michael Faraday enters and begins the first of his six lectures on the chemical history of a candle. As he commences his exploration and ignites the audience’s curiosity, he remarks:

‘But how does the flame get hold of the fuel? There is a beautiful point about that – capillary attraction. “Capillary attraction!” you say – “the attraction of hairs.” Well, never mind the name; it was given in old times, before we had a good understanding of what the real power was.’1

With this remark, Michael Faraday has provided a flicker of illumination on the theme of this article: the potential for words in science to promote understanding or to confuse and obfuscate. When Faraday introduced the term ‘capillary attraction’ to his audience, he immediately dismissed it as misleading because of its reference to hairs (capillaris is the Latin word for hairs). He states the term was assigned when the true ‘power’ (another interesting choice of word), or mechanism, was not known. This suggests he thought the term was initially assigned because it was thought the movement of the liquid was caused by the attraction of tiny hairs on the surface of the wick.

Routes to understanding

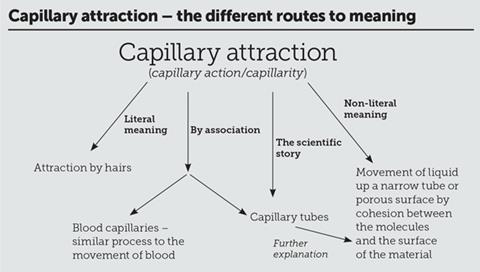

I have used capillary attraction as an example to show there are several potential routes to develop understanding of a scientific term (see panel). The literal meaning and knowledge of the Latin origins of the English word is the first route. Often, this is a successful route, but in this case it leads to an incorrect conclusion, as Faraday demonstrated.

To understand a word’s origin and the process it represents, we need to be aware of the second route to a meaning via the scientific story.2 The term ‘capillary attraction’ was ascribed in the 17th century after it was noticed that water rises within a capillary tube (a tube with an internal diameter of ‘hair-like’ thinness) so is attracted to the tube’s walls.3 This is an apparently logical term to give to the observation in this context, which can lead to an explanation of the mechanism involved.

200 years on, when knowledge and use of Latin was more prevalent than today, Faraday recognised its potential to cause confusion. His response, somewhat disappointingly, was to dismiss the term and expect his audience to simply accept it. As such he is tending towards our third route – the non-literal meaning. The original meaning of the term has been lost and we are simply expected to learn the explanation. This common route removes the potential for the term to provide an insight and explanation of the process and encourages rote learning.

150 years later, has anything changed? ‘Capillary attraction’ is a term that is still used but perhaps is more frequently referred to as ‘capillary action’. This, in itself, does not seem to be an improvement as it implies the action of hairs rather than attraction. Alternatively, there is ‘capillarity’, which also retains the ‘hair’ root of the word. Nowadays, however, fewer people have the knowledge of Latin to be immediately confused by this. Natural curiosity, though, leads us to wonder why it has acquired this term and we may try to make links with other similar words. This is our fourth route to meaning – by association. In this instance, we may think of a capillary tube and find a way to the correct explanation, but more likely is to envisage the tiny blood vessels – ‘capillaries’. Is there a connection? Does capillary action occur in capillaries? Is it the action of capillaries? After all, they both relate to the movement of fluids.

Language itself is fluid and changes over time. Is it not time we reflected on some of the words that we use and whether there are more accessible and appropriate alternatives? Do we actually need a term for this? Would it be sufficient to simply explain the phenomenon in terms of cohesion and adhesion (two further challenging words) of water molecules? Is it an artefact of science that specific names have been assigned excessively to phenomena and processes that only serve to isolate the scientific community from the public at large?

As chemistry educators, it is essential we imagine ourselves in the position of someone sitting in the auditorium at the Royal Institution with little knowledge of science and ask ourselves whether the language and words we use help or hinder understanding of the phenomena we are seeking to explain. Indeed, if I could go back in time and be Michael Faraday’s scriptwriter, I would have liked to have suggested a couple of alternatives (box 1).

Box 1: The alternative Faraday scripts

Exploring the scientific story

‘But how does the flame get hold of the fuel? There is a beautiful point about that – capillary attraction. “Capillary attraction!” you say – “the attraction of hairs.” I say “no – certainly not!” This name was given by the eminent scientist Robert Boyle two hundred years ago when he observed water rising against the force of gravity within glass capillary tubes as fine as a hair on your head.’

Removing unnecessary terms

‘But how does the flame get hold of the fuel? There is a beautiful point about that – the candle wax molecules are attracted to each other and to the wick such that they are able to rise against the force of gravity.’

Words as more than labels

Capillary attraction is an example of a scientific term becoming a label for a process rather than an interpretative tool. Clive Sutton argued that words are a much more powerful and useful aid to our understanding when we are aware of the stories behind them.2

For example, consider the case of ‘benzene’ – a ubiquitous and important term introduced early in organic chemistry and for which several scientific stories may be told. Firstly, there is the well-known ‘structural’ scientific story about Kekulé’s snake dream as he pondered benzene’s chemical structure. Not the most exciting of scientific stories but useful in appreciating the development of scientific ideas and a visual representation of the ring structure. Secondly, there is the ‘structural/reactivity’ story with the development of an explanation of benzene’s low reactivity, despite appearing to contain three double bonds. Here, a teacher can lead students into a state of cognitive dissonance where practical observations, such as a lack of reactivity with bromine water, do not agree with predictions based on a carbon–carbon double bonded structure.

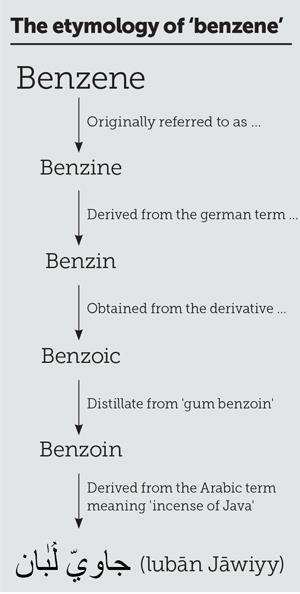

But what about the ‘why is benzene called benzene’ story? One can make a structural connection to the suffix ‘ene’ and the presence of carbon–carbon double bonds. But, for example, why is it not called cyclohexa-1,3,5-triene? Where does ‘benz’ come from? Have you just made an association with an expensive German car? If so then you are, inadvertently, on the right lines because the etymology of benzene is that it is derived from the German word ‘benzin’ (see panel). This word, in turn, was derived from benzoic acid, which was initially isolated from gum benzoin. Gum benzoin is a resin from the Styrax genus of trees that is famed for its fragrance and is commonly used in church incense (frankincense). Benzoin itself is derived from the Arabic, لبانجاوى (luban Jawiyy), which translates as ‘incense of Java’.

Exploring the origins of this word has turned benzene from having an arbitrary, functional chemistry meaning with little association to the actual word, into a substance whose origins are grounded in the human history of the past 2000 years.

Making connections

This etymological or ‘word origin’ scientific story evokes images of traders traversing the spice route and exchanging this exotic and valuable substance until it eventually reached our shores. It provides valuable opportunities to demonstrate chemistry’s historical and cultural origins as well as connections with other significant chemistry words. For example, the term ‘organic’ is now better contextualised as we can see how this substance originated from a plant. A bottle of benzoin essential oil can easily be passed around a class and suddenly the origin of the term ‘aromatic chemistry’ makes more sense.

We can then make links to perfume manufacture and cosmetics or ideas of early chemists heating up this curious substance to find out more about it. More modern linguistic links may be found with ‘benzin’ or ‘benzina’, the German and Italian words respectively, for petrol. This can lead to a discussion of the occurrence of benzene in fuel and potential opportunities to develop scientific literacy. We can also consider the confusion with phenol (surely this should be benzenol?); the only way to logically show the link between the words phenol and benzene is by considering the alternative etymological route of the French word ‘phène’ for benzene. This may lead to stories of competing chemists discovering chemicals and developing alternative names. If you still have the stamina, you may then be tempted to consider carbolic acid and toluene – the connections go on and on.

So, while previously the word benzene may have been taken for granted as a label for a particular chemical, benzene is now a much more exciting and meaningful word that places this compound within human history. This is a worthwhile strategy in any teaching environment but may be particularly useful for teachers working in multicultural environments. These word origin stories can be used to show the connections between different languages and cultures and help engage a diverse student cohort.

The common roots of words

Another etymological tool for chemistry students is to understand the common roots of words so they improve their reading skills and interpret new and unfamiliar vocabulary. Lactic acid, for example, is a term many students will be familiar with as a product of anaerobic respiration and the cause of cramp. There are many other words that share the common root of ‘lact’, which may be less familiar to students, such as lactate, lactose, galactose, alactic, lactamase and lactation. By exploring the meaning and origin of this common root to the words, the word gains more meaning and students are more able to ‘decode’ new and unfamiliar vocabulary.

The ‘lact’ root is derived from the latin for ‘milk’ but there are very few of these words, with the exception of lactation, that you would associate with milk. So why is a substance associated with our muscles named after milk? Once again, we must delve into the history of science, which informs us that lactic acid was first isolated from sour milk by Carl Wilhelm Scheele in 1780. Hence, the origin of the word ‘lactic’ becomes clear and it also tells us the other related words are likely to have something to do with milk. If we are aware of other word roots as well, then new words can be translated and meaning determined without prior knowledge of the word. For example, the root ‘ose’ refers to sugars, so lactose and galactose are likely to be sugars found in milk; or ‘a’ at the front of a word refers to ‘not’ so ‘alactic’ suggests ‘not lactic acid’. As J Dudley Herron stated:

‘Discussion of word histories can add a human touch to the teaching of science as well as improve the student’s understanding of science and help students develop word-attack skills’ (referring to developing the reading skill of recognising new words formed by adding prefixes and suffixes to root words).4

So the next time you are using scientific words with students, try to not simply see them as an arbitrary label for a chemical or a process or an idea. Instead, try revealing the story behind the word and use it as an interpretative tool to engage with and support the understanding you are seeking from your students.

Simon Rees is head of foundation science programmes at Durham University

References

- M Faraday, The chemical history of a candle, 1861 (bartleby.com/30/7.html)

- C Sutton, Words, science and learning. Open University Press, 1992 (amzn.to/29xFPTz)

- R Boyle, New experiments, physio-mechanicall, touching the spring of the air and its effects. 1660 (bit.ly/29sugO5)

- J D Herron, The chemistry classroom. Americal Chemical Society, 1996 (amzn.to/29rjbQO)

1 Reader's comment