The antidote that can stop an opioid overdose in its tracks

Naloxone was originally published in Chemistry World as part of the Chemistry in its elements: compounds series.

‘[It] is not a pleasant experience. It takes all the drugs out, so you go into instant withdrawal. I can remember coming round and feeling really ill – cold, shivering, aching. But without it I would have died.’

This is how former drug user Karl Price from Birmingham, UK, described being injected with naloxone. Karl had overdosed on heroin in a public toilet and slipped into a semiconscious state. The opioid was flooding his system, causing his breathing to slow. Had his friend not administered the life-saving antidote, he would have suffocated. Karl’s experience reflects that of thousands of other drug users that have been saved by naloxone from an otherwise fatal overdose.

Over the last two decades, the number of deaths from opioid overdoses has risen dramatically. In the United States, 64,000 people died from overdoses in 2016, 21% more than the year before. Overdoses have overtaken car accidents as the main cause of death for people under 50.

The drugs responsible for this epidemic include many essential painkillers like oxycodone, tramadol and morphine, but also substances that are usually classed as illicit, like heroin. In the last few years, fentanyl has started to hit the streets. 100 times more potent than heroin, it easily leads to overdoses as drug users aren’t aware of what they are taking.

Once in the brain, opioids bind to specialised receptors. These receptors normally bind to endorphins, the body’s own stress reducing hormones. When confronted with synthetic opioids, they can become overwhelmed. Writing in The Guardian, Marc Lewis, a neuroscientist from Radboud University in the Netherlands, described the impact of opioid drugs as a ‘hurricane’ compared with endorphins’ ‘summer breeze’. Opioids trigger feelings of euphoria and drowsiness. Heart rate drops and breathing slows. During an overdose, breathing can become dangerously slow or stop entirely.

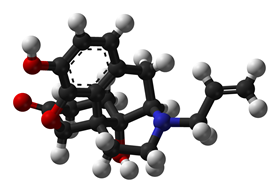

Naloxone can instantly reverse these effects. As a competitive opioid receptor antagonist, the compound kicks out the opioids from the receptor. Naloxone was developed in the 1950s, during a time when scientists were scrambling for an antidote to counter the addictive effects of morphine and heroin. However, most of the drugs developed for this purpose had dangerous side effects. Eventually chemists came up with the idea that only an opioid could counter another opioid. Naloxone’s core molecular structure is that of a classic opioid, but has no painkilling or euphoria-inducing properties.

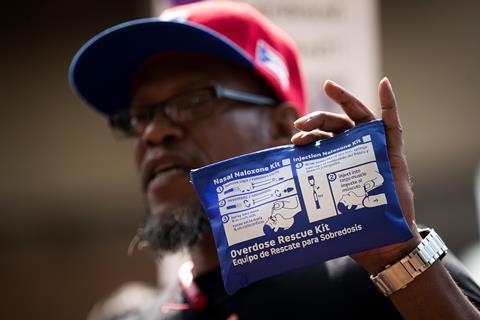

Since 1971, naloxone has been approved to treat overdoses. However, the antidote only works if it administered quickly. By the time emergency services arrive, it is usually already too late. In April 2018, the United States surgeon general issued a rare national advisory: people should add naloxone to their first aid kits and learn how to use it.

The instructions are straightforward. Naloxone comes as liquid that is injected into the muscles of the thighs or arms, where it acts within a minute. There is also a nasal spray version that takes a little longer to take effect. There’s no risk of overdosing on naloxone, it isn’t addictive and has little effect on people who haven’t overdosed. In most US states, the opioid antidote is sold in pharmacies over the counter, without prescription. Its price, however, varies wildly, peaking at $100 per dose as demand for the compound has risen sharply in the last few years.

Although naloxone has saved more than 27,000 lives over the last two decades, some say it is too expensive, or that it enables – rather than stops – drug use. Indeed, naloxone causes a person to go into instant withdrawal including all the extremely unpleasant symptoms that come with it. This often means they are more likely to take drugs again either immediately or later. A study by two US economics researchers warned that ‘access to this life-saving drug may unintentionally increase opioid abuse by providing a safety net that encourages riskier use’.

The study, however, was widely criticised for avoiding the stringent peer review process as well as its questionable use of data and statistics. Upon closer examination, there seems to be little connection between naloxone availability and opioid use. Healthcare professionals agree that naloxone doesn’t treat addiction. An overdose that requires naloxone can, however, be the tipping point that makes drug users seek long-term addiction treatment – it gives those worst affected by the opioid epidemic another chance at life.

No comments yet