Why chopping onions can turn on the waterworks

Propanethial-S-oxide was originally published in Chemistry Word as part of the Chemistry in its elements: compound series.

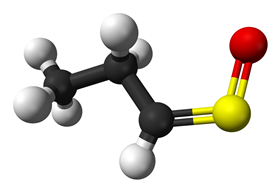

Grab a knife and slice into an onion, and you’ll quickly feel a stinging sensation and tears starting to flow. You’re suffering from the effects of a chemical known as ‘lachrymatory factor’, or propanethial-S-oxide (sometimes called thiopropanal-S-oxide) – an airborne sulfur-containing organic chemical that is similar to tear gas. Compounds that make you cry are known as lachrymators, from lacrima, the Latin word for tears. When propanethial-S-oxide comes into contact with the surface of the eye, it reacts with water to create an acid that stimulates a nervous response, triggering tears to wash the irritant away.

However, you may be confused to learn that onions contain no propanethial-S-oxide at all – so where does it come from? Similar to the way in which a glow stick only lights up when two chemicals are mixed inside it, onions only produce propanethial-S-oxide when their cells are damaged, mixing together chemicals and triggering a reaction that produces the stinging substance. Initially it was thought that the onion’s irritant was produced in a single-step reaction, catalysed by the enzyme alliinase. But in 2002, Japanese scientists discovered that it’s actually a two-step process, publishing their findings in Nature.

When an onion cell is damaged, little biological bags filled with alliinase open. This alliinase enables water and S-1-propenyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide to react together to produce a variety of sulfurous compounds. One of them – 1-propenyl sulfenic acid – is then converted into nasty, stingy propanethial-S-oxide by another enzyme, lachrymatory-factor synthase.

If you’re a fan of cooking with alliums (that’s the vegetable family that includes onions, leeks, chives and garlic), you’ve probably also noticed that red and white onions cause the most tears. Little spring onions don’t bring on the waterworks, because they contain much lower levels of the enzymes involved in propanethial-S-oxide formation.

Of course, onions don’t go to all this effort just to bring tears to a chef’s eyes. Rather, propanethial-S-oxide is thought to be a natural defence against being eaten by animals. It can also kill bacteria and fungi, making it a useful (albeit mild and slightly unpleasant) antibiotic. In fact, onion juice was used to treat gunshot wounds in the American Civil War. Ancient Roman polymath Pliny the Elder recommended onions for treating everything from dog bites to hair loss and mouth ulcers. He also believed that onions could be used to improve vision, by making the hapless patient smell the vegetable until tears started to flow, or even rubbing the juice in their eyes – should have definitely gone to Specsavers, Pliny…

Today, alliums are touted more for their nutritional benefits than their medicinal ones. Their sulfurous compounds are claimed to have a wide range of health benefits, from cancer prevention through to fighting asthma, cardiovascular disease and diabetes. However, onions get their sulfur from the ground they grow in – which is why some onion varieties grown in low-sulfur soils are less pungent. In developed countries, much of the sulfur in soil comes from sulfuric acid deposited in acid rain, created from sulfur dioxide released into the atmosphere by industrial processes such as coal burning. As countries like the UK have cleaned up our act, reducing sulfur dioxide emissions, so the amount of acid rain has also gone down. This could be having an impact on the potency, flavour and possibly the nutritional benefits of onions and other sulfur-packed veg.

Even so, today’s onions are still pretty pungent. So what’s the best way to stop the sting? Speaking as a contact lens wearer, I find that they reduce the effect a lot compared with wearing glasses. Swimming goggles are another option, although hardly a trendy look in the kitchen, while a very sharp knife will minimise cellular damage and reduce the amount of propanethial-S-oxide reactions going on. Another idea is to try cooling your onions prior to chopping, which might help to reduce the volatility of their tear-inducing gas.

Finally, you could just wait for the no-cry onion to hit the shelves. A New Zealand-based food technology company has developed a genetically modified onion that switches off the lachrymatory-factor synthase enzyme responsible for producing propanethial-S-oxide, instead producing alternative compounds that might even be better for health.

No comments yet