Fighting in Ukraine is endangering production, because the country is one of the biggest suppliers of a vital component, neon

-

Download this

Use this story and the accompanying summary slide for a real-world context when studying minerals with your 14–16 learners.

Download the story as MS Word or PDF and the summary slide as MS PowerPoint or PDF.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is expanding the list of conflict substances by threatening global supplies of neon.

The EU’s Conflict Minerals Regulation only covers tin, tantalum, tungsten and gold. These minerals and metals either sometimes finance armed conflict or come from minerals mined using forced labour. The metals have a wide range of consumer uses and legislation exists to keep the conflict minerals out of industrial supply chains. But the war in Ukraine is creating conflict substances of a different kind. It is affecting global supplies of high-purity neon gas needed to make semiconductors for all sorts of electronic items.

Neon production

Name in lights

Famous for its red-orange glow in neon lights, the inert gas occurs naturally in the atmosphere at low concentrations of around 18 parts per million by volume. Producers extract it by cooling air until it liquefies and separating out fractions based on boiling points.

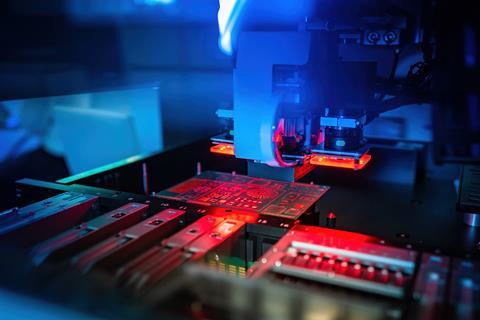

Around 70% of neon is used as a buffer gas in the excimer lasers that etch features onto semiconductor’s silicon wafers. The excimer lasers provide highly focused ultraviolet rays and are also used in laser weaponry and for eye surgery.

Around the world, only a limited number of companies are set up to produce the ultra-pure (99.999%) neon gas required for the lasers.

Global supply

Until the war, Ukraine produced around half of the global supply of high-purity neon, according to analysts. Production was mainly at a Cryoin facility in Odessa and an Ingas plant in Mariupol, a city now sadly destroyed by bombing.

The production facilities recover neon as a by-product of steel manufacturing. Steel producers separate air to control levels of oxygen and nitrogen delivered to the blast furnace. Neon, krypton and xenon are by-products of this air separation.

Because neon is present in such low concentrations it can only be economically recovered from very large steel plants. In other words, to get meaningful amounts of neon you need to process large volumes of air.

Could conflict also dent catalytic converter production?

Russia supplies a host of valuable metals to the rest of the world, including nickel, gold and platinum-group metals (PGMs). The EU lists PGMs as ‘critical raw materials’, with Russia being the second largest supplier, after South Africa, according to its statistics. Russia has around 40% of the world’s reserves of the PGM palladium, which is a critical component of catalytic converters for cars. Nickel is not critical but is widely used in stainless steel and lithium–ion batteries.

Alternative supplies and recycling

Looking elsewhere

China is already a significant neon supplier and production facilities in other countries could increase production to help fill the gap. For example, in January 2022, a South Korean steel producer set up a new neon production facility using a large air separation device. However, it could take many months to fill the gap left by halting Ukrainian production.

Semiconductor producers are also looking at ways to conserve neon gas by making processes more efficient. For example, Japanese laser company Gigaphoton has developed a neon gas recycling system, which collects the used gas from lasers, removes impurities and injects it back into the system.

Put this in context

Add context and highlight diverse careers with our short career videos showing how chemistry is making a difference and let your learners be inspired by chemists like Zubera, a research fellow in battery recycling.

Starter slide by Neil Goalby

Emma Davies

rsc.li/37y64wp

Downloads

EiC starter slide Neon A conflict material

PDF, Size 0.2 mbWar threatens semiconductor production

Handout | PDF, Size 0.14 mbWar threatens semiconductor production

Editable handout | Word, Size 0.46 mbEiC starter slide Neon A conflict material

Editable handout | PowerPoint, Size 12.27 mb

No comments yet