Use extended periods of talk to improve the quality of students’ responses in the chemistry classroom

Early in my teaching career I used the Thinking science programme of lessons. One of the tenets of these lessons was metacognition, where teachers ask students to talk to the class and share decisions they had made. I subsequently integrated a pedagogy of talk and an exploration of students’ thinking into my teaching style and philosophy.

Early in my teaching career I used the Thinking science programme of lessons (bit.ly/3Wqapba). One of the tenets of these lessons was metacognition, where teachers ask students to talk to the class and share decisions they had made. I subsequently integrated a pedagogy of talk and an exploration of students’ thinking into my teaching style and philosophy.

During my classroom teaching career, I didn’t see much discussion of or research into talking by students. I always felt there was value in exploring students’ ideas and giving them opportunities in lessons to talk about their thinking. When I came to study for my PhD, I decided this would be my subject.

Having been fortunate to have worked with many dedicated and skilful teachers, I was pleased when a teacher of a year 10 combined science group was happy to work with me to explore dialogic teaching. Together we created lessons which contained extended periods of talk between students as part of the school’s existing chemistry curriculum.

Structure for success

The teacher and I carefully planned the first lesson including extended periods of talk, considering what the learners would talk about. The teacher told the students this lesson would be different from usual and that we were interested in their ideas.

We divided students into self-selecting groups to talk to each other about their ideas and come to a consensus. The students said they could only engage in dialogue effectively if they were able to decide who was in each group as they felt more able to share their ideas with people they trusted.

For each lesson, we asked the groups to respond to a question.

| Lesson | Question |

|---|---|

| Salts from metals | Explain what acidic and alkaline solutions are like. |

| Methods to make salts | Write a method to prepare a sample of a soluble salt. |

| Ions and salts | Ions are important when you think about reactions of acids. Why? |

| Strong and weak acids | What’s the difference between strong and weak acids? |

| Electrolysis | Describe what happens at each electrode. |

| Testing for gases | Why do some gases form during electrolysis? |

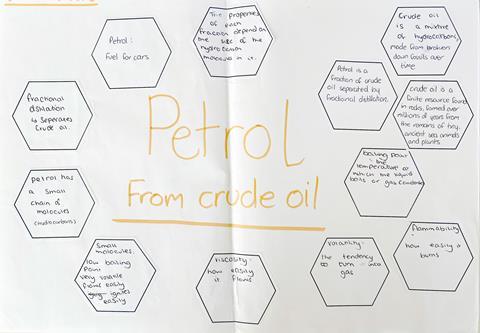

| Hydrocarbons | How do we get petrol from crude oil? |

| Life cycle assessment | What is a life cycle assessment? |

| Measuring rate of reaction | How do you measure rate? |

| Collision theory and surface area | How does surface area affect the rate of a reaction? |

| Rates and temperature | Describe how to carry out an experiment to measure the rate of reaction when you change the temperature. What do you think the outcome will be and why? |

We designed the questions to prevent simple recall. They required the students to explore their existing ideas and experiences. Students evaluated each other’s ideas and the relevance of what they said. This made their talk dialogic because they reflected upon, negotiated and responded to each other’s ideas.

To support dialogue, we provided each learner with paper hexagons to write their ideas on and each group a large piece of paper they could stick their hexagons to for the different lessons and topics.

While students worked on the questions, the teacher’s role was minimal. They did not circulate or interrupt the groups. We found that when students asked the teacher for help, the group’s dialogue came to a halt.

Better learning with dialogic teaching

Over the course of the research, students became more proficient at organising themselves and creating their responses. The time used for dialogue also increased, from five to 20 minutes.

What students said

One groups’s response to ‘How do you measure rate?’ was:

‘So to measure the rate of reaction, you can use a timer to record how long a reaction takes or how much product the reaction produces within a certain time, such as how long it takes for a solution to turn cloudy, or how much gas is produced every 10 seconds. The longer reaction time means a smaller rate of reaction, or the less collisions that happen between particles meaning the lower rate of reaction, it is also necessary for experiments to be controlled properly to measure the rates accurately.’

And in another lesson the groups discussed ‘What is a life cycle assessment?’

‘We all collectively decided that the life cycle is an assessment of products and how they have environmental impacts. And that has a process of like through their resources, the processing, the product manufactured, the distribution, the uses of and the end of the life cycle. And all of these are assessed individually, so that companies are able to know where they have to improve in from the environmental side of things. And because there is three different types of damage, so damage to the environment, damage to the human health and damage to the resources. And it’s important that the companies have this conclusion so that they can make the companies more sustainable.’

One groups’s response to ‘How do you measure rate?’ was:

‘So to measure the rate of reaction, you can use a timer to record how long a reaction takes or how much product the reaction produces within a certain time, such as how long it takes for a solution to turn cloudy, or how much gas is produced every 10 seconds. The longer reaction time means a smaller rate of reaction, or the less collisions that happen between particles meaning the lower rate of reaction, it is also necessary for experiments to be controlled properly to measure the rates accurately.’

And in another lesson the groups discussed ‘What is a life cycle assessment?’

‘We all collectively decided that the life cycle is an assessment of products and how they have environmental impacts. And that has a process of like through their resources, the processing, the product manufactured, the distribution, the uses of and the end of the life cycle. And all of these are assessed individually, so that companies are able to know where they have to improve in from the environmental side of things. And because there is three different types of damage, so damage to the environment, damage to the human health and damage to the resources. And it’s important that the companies have this conclusion so that they can make the companies more sustainable.’

These examples demonstrate that giving students the opportunity to explore and share their own experiences with their peers seems to create an environment where ideas can flourish and mature, leading to improved responses. And what students have to say is important in developing their understanding of chemical concepts.

In my experience, the development of dialogic teaching techniques is an important addition to a teacher’s pedagogic repertoire. My ongoing PhD study will explore in far more detail what students discuss and how it develops their understanding. I also hope to be able to continue my research and develop a guide for the dialogic teaching and learning of chemistry in secondary schools.

Nicklas Lindström is a senior lecturer at the University of Roehampton and a qualified science teacher

No comments yet