Cross-disciplinary debate supports critical thinking and discussion skills

Integrating knowledge and modes of thinking from multiple disciplines supports cognitive advancement in ways that might be unlikely through single-disciplinary means. At Northampton School for Boys, the science and English departments are working together to better develop students’ reasoning skills through classroom and online debate. The project focuses on socio-scientific issues – topics grounded in science that impact wider society and result in differing perspectives and disagreement.

Our interdisciplinary learning project uses Science Debate Kits to prompt discussion on subjects such as Mars missions, vaccination and privacy. These conversations improve students’ fluency around scientific questions, ethical issues and the power and limitations of science.

The school virtual learning environment hosts preparatory materials, video and website links, as well as debate kit materials that support or refute a claim.

The claim is introduced in an English lesson and the argument is scaffolded using sentence stems to model bridges between the claim and supporting data, helping students identify the conditions under which an argument is true. Equally, counterarguments are exhibited to encourage the students to form their own opinions.

Students then write comments in an online forum as a home learning task. We have found that assigning roles expressing a particular viewpoint facilitates the debate. Finally, the students debate the claim in a subsequent English lesson. Enforcing strict time limits keeps the debate succinct.

A framework for argument

Following the debate, we discuss wrong ideas and why they’re wrong and why the right idea is right, to help our learners examine their reasoning and identify their preconceptions. This empowers students to make judgments based on evidence, and to evaluate factors such as the language and logic used to make a case.

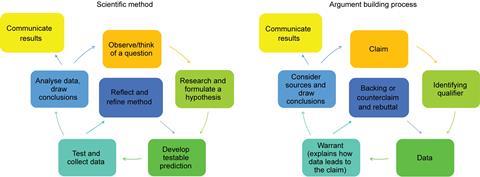

The English department introduced us to Toulmin’s framework, an analysis tool used to determine how well the different parts of an argument work together. Such analysis can lead us to change our minds about the strength of an argument in a manner akin to the scientific method, in which scrutiny of collected data may support or refute our hypothesis.

To use Toulmin’s framework more effectively with our students, we’ve modified the model to make it directly comparable to the scientific process. This reflection on the debate helps students develop the argumentative writing skills required in both English and science and builds confidence for engaging in dialogue.

Evidence-based arguments form the basis by which scientific knowledge is used, tested and revised. To participate in these arguments, students must learn how to evaluate and use evidence. It is our hope that by working together, using a shared language, we will be able to better support our students develop their critical thinking, reasoning and debating skills.

With thanks to Shirley Morrison for her wisdom, advice and enthusiasm.

Additional resources

- Bonding chemistry and argument: teaching and learning argumentation through chemistry stories

- English Speaking Union oracy in your classroom lesson plan template

- STEM learning Ideas, evidence and argument in science (IDEAS Pack)

- I’m a scientist get me out of here offers various debate kits.

References

B Crujeiras-Pérez, M Pilar Jiménez-Aleixandre, Argumentation, Chemistry Education: Research, Policy and Practice, 2019, DOI: 10.1039/9781788012645

S Toulmin, The Uses of Argument, Cambridge University Press, 1958, DOI: 10.1017/CBO9780511840005

No comments yet