Jo Moules cuts through the confusion and gets to the heart of formative assessment

Only occasionally does a publication change national policy and practice, but that’s what happened with the publication in 1998 of Paul Black and Dylan Wiliam’s book Inside the black box.1 That short review of the nature and value of formative assessment, along with follow-up publications from the same authors,2 created a national agenda for assessment. Its impact can be seen in the assessment policies of most schools in the UK and in aspects of classroom practice such as ‘wait time’ and ‘no hands up’.

But what is formative assessment? A brief review of the literature reveals a variety of definitions. They vary in complexity and detail – some are useful, others less so. In the belief that simple is both helpful and less liable to misinterpretation, here’s my classroom-based description of formative assessment:

- There is a gap between where learners are and where we want them to be.

- Teachers cannot close the gap, only learners can close the gap.

- To do this they need to know where they are, where we want them to be and have some ideas about how to make the journey between the two.

Any activity that illuminates this contributes to formative assessment.

Speak up at the back

The critical principle underpinning formative assessment is the use of dialogue between learners, and between learners and teachers, to reveal what learners are thinking. Talk contributes to both learning and assessment, providing a bridge between the two. As Black and Wiliam put it, ‘Opportunities for pupils to express their understanding should be built into any piece of teaching, for this will initiate the interaction whereby formative assessment aids learning.’

I find it ironic that primary schools spend time and effort building up learners’ ability to use language effectively to discuss, argue, explain, explore and express themselves and their ideas, only to see these skills undervalued in many secondary schools. Of course there are secondary classrooms where dialogue is viewed as an important element of lessons – but there are many where it isn’t.

Chemistry classes in particular can benefit from classroom dialogue. Productive talk leads to scientific thinking and scientific enquiry.

Neil Mercer’s work on exploratory talk highlights the key benefits.3 Mercer describes how talk encourages people to ask questions and make reasoned challenges to ideas. He emphasises the importance of everyone being encouraged to contribute to a joint decision in answering questions and solving problems.

Similarly, Robin Alexander's work on dialogic teaching reminds us deep learning is more likely to occur where the voices and ideas of learners are valued in lessons, and talking together is viewed as a central part of learning.4

Simplicity is often the key to effective classroom teaching. In an increasingly busy and challenging school environment, it is important to be able to deliver a lesson as well at 2pm on Friday afternoon as you could at 10am on Monday morning. Teachers need quick, simple and effective ways to support assessment and learning.

There is nothing more informative, simple and direct than providing a stimulus for talk, stepping back, listening, assimilating and evaluating. This helps us to understand what learners are thinking and what the next steps in learning should be.

What factors lead to productive talk?

If talk is to be useful as a formative assessment tool it should engage students, be purposeful, and present alternative possibilities.

The stimulus and discussion need to be engaging

If learners aren't engaged they will not talk productively; if they do not talk productively, they will not learn as much as they could.

The richest and most productive questions are those learners ask for themselves. Most of us have experienced moments when a learner asks the perfect question at the perfect moment (and, of course, the wrong question at the wrong moment). Spontaneous opportunities like these need to be seized and moulded whenever we encounter them.

Developing a culture of asking questions will support this. The use of exciting demonstrations, surprising revelations and interesting practical work can create opportunities to engage learners. However, this flash–bang approach is difficult to sustain and not every topic lends itself to it. Skilful questioning from teachers and opportunities for dialogue promote a minds-on approach to complement hands-on enquiry in science.

Talk must also have a clear purpose

Discussions need a supportive framework in which dialogue can take place, limited in scope but not constrained in the ideas it explores.

There should be a clearly defined outcome to the discussion, such as a problem to solve where a clear decision is the goal. The abstract nature of some of the ideas in chemistry creates challenges, so setting the discussion (wherever possible) in familiar contexts, using concrete and everyday examples, makes dialogue accessible and open to all.

Ensuring that high-achieving learners engage is not usually difficult, as many of them are self-motivated and take pleasure in learning. Lower-achieving learners generally need more structure and context, with down to earth and personally relevant examples. In other words, they need a reason to ask questions, suggest ideas and seek a solution.

Dialogue should explore alternative viewpoints

Talk should leave scope for debate and lead to open thinking and new ideas rather than well-rehearsed responses.

Closed questioning that leads to a series of textbook correct answers or disappointingly incorrect ones generally tells us little about what has or has not been fully understood. An open discussion between learners, exploring a range of possible ideas, tells us far more about where learners are and how to help them move forward in their learning journey.

The idea that misconceptions are contagious is wholly misguided. Misconceptions are widespread, and learners will cling to them unless there are opportunities to express them, attempt to justify them and discover their limitations. Alternative viewpoints create cognitive conflict and this is a superb stimulus for learning.

Finding a suitable stimulus for talk

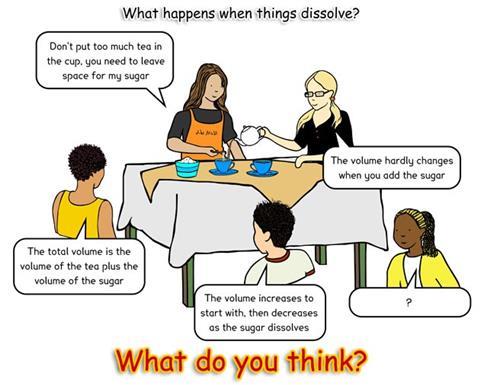

One quick, simple and effective way of getting learners to engage in discussions about chemistry is to use concept cartoons.5 These are popular with learners as well as being very manageable for teachers. They present a dialogic model of learning, where all the characters in a concept cartoon contribute different ideas to the discussion. This provides an explicit illustration of exploratory talk and the only way the characters can resolve their difference of opinion is through evidence and reasoning.

The latest set of concept cartoons explores ideas for older learners, including a significant number of chemistry examples.6 They are a great way to get learners talking about chemistry as they encounter new ideas, or review their learning before moving on to more complex ideas.

For example, figure 1 deliberately uses an everyday situation to make it accessible. It exposes and explores the misconception that dissolved solids 'disappear', and opens up a discussion about what actually happens to dissolved solids.

This may not be a thought that has ever crossed the minds of learners. Presenting four plausible but contradictory answers promotes cognitive conflict and motivates those discussing it to seek a solution.

Students might choose to side with one of the characters or they may have other ideas of their own. Either way, the discussion draws us into a constructivist approach to learning where a common and agreed understanding is the goal. Allowing learners to side with a particular character encourages everybody to contribute and supports less-confident learners. In this way we develop not only students’ knowledge and understanding, but also their social skills, their ability to take risks in exploring their views and to work successfully with others.

The follow-up activities encourage learners to explore and find out about this problem by trying them out, creating a clear purpose for enquiry-based learning and collaboration.

What is the teacher’s role?

A teacher shouldn’t simply to give students the ‘right’ answer, or evaluate the rightness or wrongness of their answers.

Most of the time a teacher needs to suspend judgment about students’ ideas and listen carefully. By listening we learn. We learn about who has which ideas, whether they are firmly held or tentative and to what extent their ideas are scientifically acceptable. We also learn about how effective our teaching is and how we might need to adjust it to make learning better.

This is a key principle in the effective use of talk for formative assessment. Talking without listening doesn’t help anyone, so we need to be effective listeners and help our learners to develop their listening skills too.

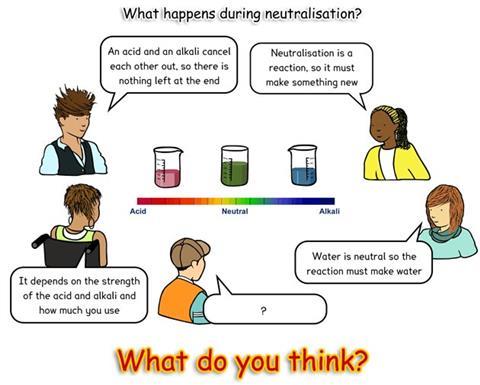

The example shown in figure 2 illustrates the importance of both listening and talking. Neutralisation is a deceptively difficult concept for some learners. It is very easy to fall back on the 'cancelling out' model as a way of thinking about neutralisation and it is possible the way we speak about it may reinforce this misconception. Equally, the concept of neutrality is one that is most readily attributed to water and some learners become drawn to this idea and miss the subtlety that a neutral solution has been formed.

In the context of answering questions about neutralisation, these alternative (incorrect) frameworks may not be a problem in the short term. However, in relation to the goal of developing a full and rounded understanding of chemistry, they will cause problems later on.

Discussion is the way to tackle this. Talking clarifies learners’ ideas by making them articulate and justify them to others (self assessment); it challenges their ideas by comparing them with those of their peers (peer assessment) and it provides valuable information to the teacher about what is or isn’t understood (formative assessment).

Going further

Teachers often overlook the background text provided with concept cartoons. After learners have explored ideas and tried to reach a consensus, they need some further stimulus to spur their discussion into its next phase. That might evolve from their own enquiry, or it could come from working with the background text for the concept cartoons.

The background text gives ideas for follow-on activities to find out more, and guidance about which of the statements makes most sense and why. Giving learners access to the background text should help them gain more ideas and insight and support them in further discussion or enquiry.

No matter which stimulus is used to engage learners, to get the most from formative assessment teachers should:

- create time for learners to talk in lessons;

- provide a focus, a context and a purpose for talk;

- recognise the value of getting learners to reveal their ideas through talk;

- use what they learn to decide how to guide students in learning.

Jo Moules is an author, CPD provider and strategic adviser at Millgate House Education

References

- P Black and D Wiliam, Inside the black box. Kings College, London, 1998 (amzn.to/2co2d5n)

- P Black et al, Working inside the black box. Kings College, London, 2002 (amzn.to/2cBLDSc)

- N Mercer et al, Br. Educ. Res. J., 2004, 30, 359 (DOI: 10.1080/01411920410001689689)

- R Alexander, Towards dialogic teaching: rethinking classroom talk (4th edn). Dialogos, 2006 (bit.ly/2c5Ti5z)

- S Naylor and B Keogh, Science concept cartoons, set 1. Millgate House Education, 2000 (bit.ly/2cJI9ZC)

- J Moules et al, Science concept cartoons, set 2. Millgate House Education, 2015 (bit.ly/1a9LP4e)

No comments yet